How Many New Songs Are Released Each Day?

It's a scary number—but here's what we do about it

Can you have too many songs?

That seems like a nice problem to have, until you start looking at the implications. They’re scary—both for musicians and fans.

Songs are like tribbles. One is cute, and you love it. Even five or ten are fine. But when you encounter a thousand of them, you run away as fast as you can.

I fear that’s happening in music right now. It’s become tribble-ized—and hence trivialized.

But let’s analyze the situation, and try to reach some conclusions. I’ll start with one tiny genre (jazz)—where it’s easier for me to wrap my mind around the numbers—and then try to assess the larger picture.

I warn you: It’s ugly.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Many jazz fans consider 1959 as the high point of the genre. That year saw the release of so many beloved recordings, including:

Kind of Blue by Miles Davis

Time Out by Dave Brubeck

Mingus Ah Um by Charles Mingus

The Shape of Jazz to Come by Ornette Coleman

Giant Steps by John Coltrane

But that short list just scratches the surface. I could easily add another 10 or 20 jazz albums from 1959 that are undisputed classics—and probably another 50 to 100 recordings that are still cherished by many jazz fans today.

But here’s the surprising twist to all this. Somebody once told me that Downbeat, the leading jazz magazine, only received around 500 jazz records to review during the entire year of 1959.

It’s hard to imagine somebody releasing a jazz record in 1959, and not submitting it for review. So this means that around 20% or more of all the jazz records released that year are still heard and admired today—after 60 years!

In the fickle world of music, that’s an extraordinary success rate. Just releasing a jazz record that year gave you a 1-in-5 chance of ongoing success into the next millennium.

Now let’s compare this with the current day. It’s a depressing story, but somebody ought to tell it straight. I guess that means me.

Nobody really knows how many jazz albums are are getting released in the year 2023. But I probably have a better sense of this than most—because I constantly hear from musicians, labels, and publicists about their new music. Sometimes I will receive 50 or more pitches on new records in a single day.

Here’s my best guess: I’d estimate that somewhere between five and ten thousand new jazz recordings will be issued this year.

Clearly if you judge an art form by supply—and ignore that pesky little matter of demand—we are living in a golden age. We have far exceeded anything dreamt of by jazz lovers back in 1959.

In those distant days, a music fan could actually listen to every new jazz album, and still have time to spare. Nowadays that’s impossible. There’s not a single person on the planet who can even scratch the surface of all the accumulated music.

But here’s an even more extreme comparison. Let’s ask how many of these recordings will still be heard and loved in 60 years time. I’m afraid to answer that. But we are a long, long way from 1959 when a recording artist had a twenty percent chance, more or less, of making a lasting impact.

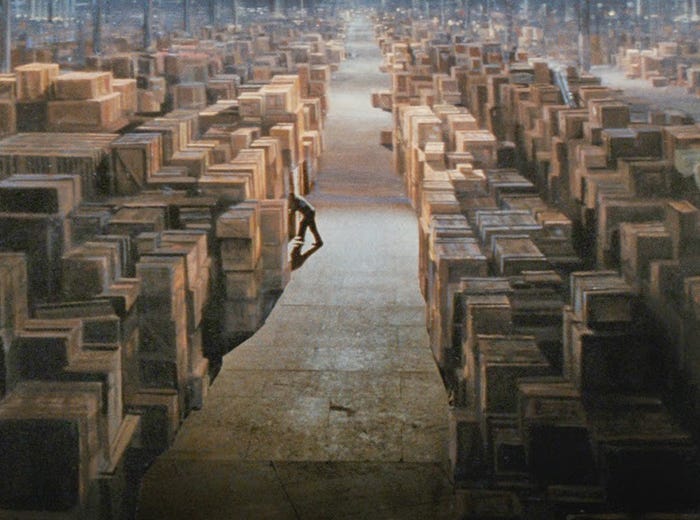

Here’s the sad truth for a musician in the current day. They can’t even begin to compete in their field, because they are almost always lost in the noise before the competition even begins.

This can’t be healthy. You flourish as a creative person when you actively compete at the highest levels of your vocation. If the actual situation is that you’re just lost in a crowd, you’re demoralized from the start. Instead of demonstrating your skills, you’re shouting out for attention—and ineffectively in almost every instance.

It’s like the difference between fighting for the heavyweight title, when you can demonstrate all your subtle boxing moves, and trying to prevail in a street riot. And that’s exactly what the music scene feels like in the current moment—a riot, with no rules or boundaries. You never win; at best, you survive.

Now let’s look for an even scarier number. How many recordings are released each year in all music genres?

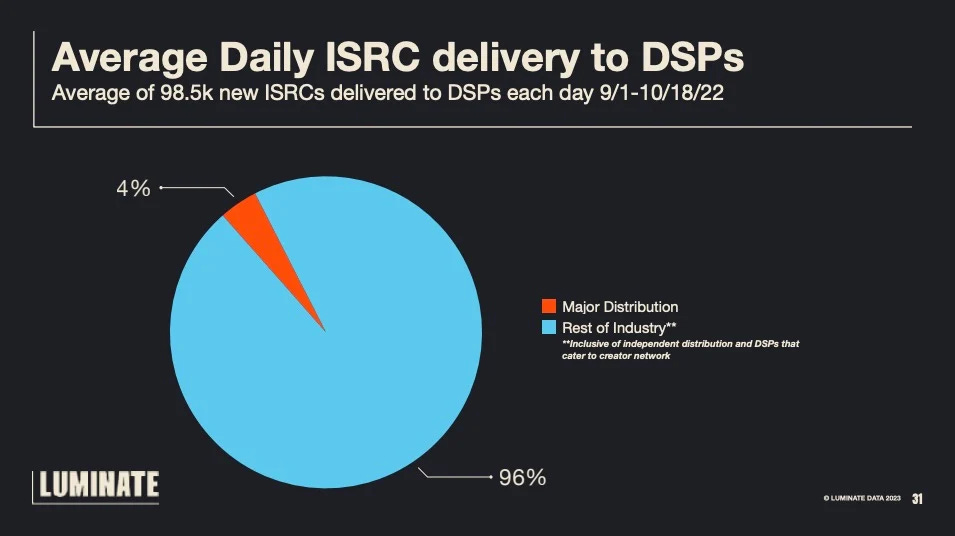

In 2019, Spotify claimed that 40,000 tracks were added each day to its platform. And by 2021, the number increased to 60,000. But last September, the CEOs of two major labels made the staggering claim that 100,000 songs were now getting released each day.

Some argued that these figures were inflated. This couldn’t really be happening.

But a few weeks ago, Billboard reported that SoundCloud added 45 million tracks over a 12 month period. That works out to around 123,000 new songs every day.

The mind reels at this concept.

Here’s another odd twist: AI is now composing music at a fast clip. As I’ve written elsewhere, you can now get customized AI songs for just a few dollars—and the music is delivered almost instantaneously.

But do we really need AI songs, if human musicians are creating 123,000 per day? I’m not sure what the saturation point is, but we must have reached it long ago. And I’m not even going to try to guess how many of these songs resemble other songs—because, after all, there aren’t an infinite number of melodic phrases in a 12-tone system.

Is there a single unsung melody left to sing? The scope of copyright infringement must be off the charts.

Here’s another twist. The numbers are still staggering even if we focus solely on the three major labels.

These three companies alone issue 3,900 tracks per day.

Now that’s a truly humbling number. Not long ago, getting a record contract with a major label put you in a small elite group. Now you’re just another face in the crowd—and that crowd gets larger every day.

Let me try to put all of this into perspective, at least as best I can. Below are my conclusions—along with some suggestions on how we ought to respond to this deluge of music.

The crisis in the arts is not on the supply side. As I pointed out in my recent ‘State of the Culture’ speech, every field of creative expression is drowning in an over-abundance of offerings. Other fields (publishing, podcasting, photography, etc.) are experiencing the same situation. Music might not even be the worst offender. Any program for the arts that ignores this—and most of them do, I hate to say—is operating in fantasy land.

Yet almost every arts-related institution in the world is focused on the supply side, almost to an obsessive degree. This feels good—we love giving money to artists. But even from a purely financial standpoint, these programs don’t do half as much good as genuine audience expansion. If you offered a musician the choice between a hundred dollars and a hundred new fans, they absolutely benefit more from the latter. It’s a no-brainer. In fact, musicians probably make more from just one loyal fan.

Let me make a cynical observation—namely that the decision-makers in these organizations who strenuously avoid audience-building projects actually prefer it that way. They really don’t want a large audience for the projects they support, which would spoil all the fun of being an elite who operates above the masses. Who knows, maybe they have also decided that the cultural narratives they prefer to support have zero chance of developing a meaningful audience, and aren’t even designed to do so. That may seem a cruel and unreasonable accusation, but all their actions support such an interpretation.

But emulating these insiders is tantamount to implementing a cultural deathwish. That’s why people who care about art as an actual force in the lives of individuals and communities must support demand-driven initiatives aiming at (1) audience education, (2) cultural outreach in schools and elsewhere, (3) cultural programming in mass media—where the lack of it has reached scandalous levels, (4) curation and gateway projects that provide entry points for new audience members, and (5) ways of turning the experience of artistry into an uplifting everyday encounter and not just a marginal activity for cliques and elites.

These are tough things to achieve, and not very glamorous. But the less we focus on the glamor angle of creativity, the better we will be. You rarely see me write about the glamorous stars (whether measured by money or reputation) in The Honest Broker, and that’s not by chance. Sure, some of them deserve all their acclaim and money. But the culture is weakened when we have such a stratified pyramid at the center of our cultural ecosystem, with a tiny number of elites at the top. I’m much happier with those medieval villages, which all had a few musicians on the payroll—and whose music was embedded in local life, even on the smallest scale and in the most intimate ways. We probably can never recapture that completely, but we abandon such ideals at great peril.

That’s why I’m not overly alarmed at the large number of songs released each day. I’m perfectly happy with a society in which many people make their own music. Of course, few of these individuals will have anything resembling a music career, but their own lives will be enriched by music-making. And there could be more outlets for this grassroots activity, if we put some effort into it—by fostering workshops, open mics, songsharing collectives, music clubs at schools, get-togethers for local performers, mentoring and outreach, music in retirement homes, a return of dancing to live music, etc.

We need to fix things before all this music-making has an uplifting social impact in any meaningful degree—but that’s not an impossible dream. Imagine the results if these thousands of neglected songs actually created thousands of social connections, even on just a local level. We don’t have the infrastructure for that today—but we could create it.

If we view things in this manner, the abundance of songs is not so alarming. It’s only the current context that makes everything so ugly. Many of these musicians have been encouraged in a pursuit of stardom by a broken culture that can never deliver even a fraction of what it promises. But if the larger context were healthier, an abundance of music-making is not a bad thing.

The only starting point is for the institutional and organizational leaders in music to turn their gaze away, even for just a moment, from the superstars on stage or fashionable grant-guzzling elites. Instead they need to take a long, hard look at the audience. They may not like what they see there, but that’s where the battle has to be fought and won. If, despite all this, they keep growing supply without worrying about demand, they’re just adding more tribbles—and to the detriment of both musicians and listeners.

“every field of creative expression is drowning in an over-abundance of offerings. “

So True!

It would be interesting to see the number of publications in any scientific discipline in one year.

We are drowning in information, yet we are starving for knowledge.

As a musician who writes, records, and performs live, this helps sum up what I’ve been observing lately. My bandmates and I along with our producer - all people that I consider to be very, VERY talented and creative - work very hard to perfect our songs and our live performances. And the audiences we do get consistently shower is with praise for what they’ve just heard or seek from us. But sometimes releasing a ew song feels a bit like adding one drop of water to the ocean. Who cares?