How I Joined the Euro Jazz Cult

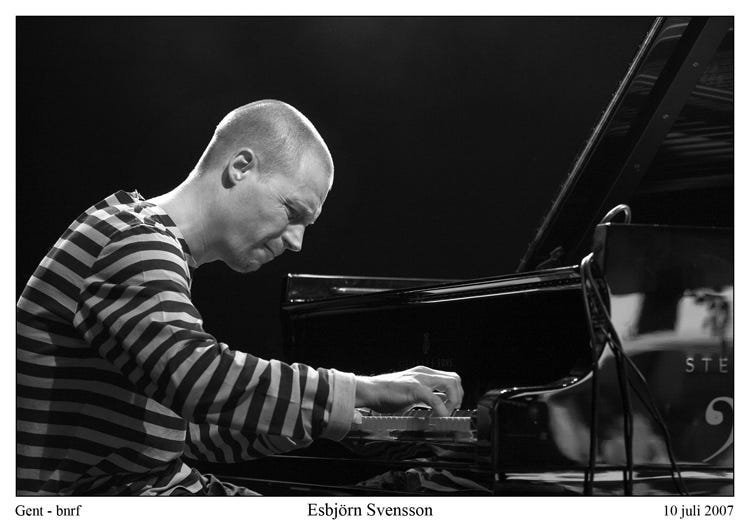

15 years after Esbjörn Svensson's death, a new album reminds us of his historic impact in globalizing the art form and changing attitudes (including mine)

This happened years ago, but I still remember it vividly. A jazz-loving friend called to tell me about EST—which he insisted I absolutely must check out.

I feared the worst. Maybe I needed to mount an intervention.

The only EST I knew about back then was a crazy cult that flourished on the West Coast during my 20s and 30s. The initials stood for Erhard Seminars Training, and involved weekend indoctrination sessions featuring (according to rumor) extreme feats of fatuous folly and mindless self-abasement. It went beyond the pale even by California’s loose standards.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

I kept my distance from all these cults (and there were plenty back then). But I had a roommate for a spell who belonged to an EST spinoff, and—much to my dismay—brought a huge cadre of new recruits to our apartment one evening for a spirited drinking-and-brainwashing session.

I went and hid in my bedroom. Needless to say, he didn’t remain my roommate for long.

So I was relieved when I learned, from my friend, that his brand of EST wasn’t a cult, but a new jazz band. The initials (sometimes presented modestly in lowercase as e.s.t.) stood for the Esbjörn Svensson Trio, which was attracting an enthusiastic following among young music lovers in Europe—and apparently without any self-degradation happening in the audience.

So EST wasn’t a cult, but a band with a cult following.

Even so, this was hardly enough to stir my interest. I hear about hot bands that I absolutely must check out every 15 waking minutes, more or less—thanks to the round-the-clock access of the Internet and the fact that every musician from here to Ultima Thule seems to have my email address. So it was only because my friend Stuart Nicholson was the band’s ardent advocate, that I started paying close attention to EST.

Let me tell you about Stuart Nicholson.

Back in those days, he was the most fervent and enthusiastic advocate for European jazz I’d ever met. In a way, he was like his own cult, but with a headcount of one. Even when I lived in Europe, which I did for two stints (in England and Italy) I’d never encountered anyone with such devotion to Euro jazz.

Let me say that this is more common nowadays (and Stuart gets some credit for the attitudinal shift), but in the late 20th century overseas jazz was expected to operate in the shadows of the US scene. In all fairness, that was a view most often espoused by New York jazz critics—or rather implied by these critics in their writings, which sometimes acted as if the only significant contributions from across the Atlantic were Django Reinhardt back in the 1930s, and a few ECM albums of more recent vintage. But until recently, even many European jazz fans had bought into the notion of stateside superiority, to varying degrees.

Stuart bristled at this close-mindedness. And I had to give him credit for knowing his stuff. He was totally on top of what was happening at that moment (or any given moment) in Europe, even at a granular level. He could tell you whether the drummers were better in Zagreb or Uppsala. He was your source if you wanted a ranking of alto sax players in Montevideo, or an update on the festival scene in Greece, or the name of the best bass player to hire for a gig in Sintra or a recording session in Bergen.

The downside was that Stuart always had something I needed to listen to—drop everything, Ted, and check it out. But he was a trusted advisor, one of my most knowledgeable sources, and he insisted that I absolutely had to share his love for the Esbjörn Svensson Trio (EST), which wasn’t just another solid Euro outfit, but was legitimately shaking up the scene with something fresh and different—and ought to get more credit for this in the US.

I’m happy to say he was right. And sad to report that EST still doesn’t have the respect it deserves in the US. And it’s too late now because Esbjörn Svensson died in the aftermath of a swimming accident a few years later.

Or maybe it’s not too late, because a posthumous solo piano release came out yesterday, almost 15 years after the pianist’s death. It gives US music media another chance to review Svensson’s life and times, and spread the word among listeners. Or maybe those US jazz radio stations, who typically passed on this artist the first time around, will give him some posthumous rotations on their playlists.

But that hardly matters, because Svensson changed the landscape of global jazz during his short time with us, even if he doesn’t have much name recognition in the genre’s native land. I could describe this change in many ways, but perhaps the most obvious impact was economic. European jazz festivals once relied heavily on touring American musicians for legitimacy and audience draw, but that’s not quite so true anymore, and the success of EST was a major turning point in this shift.

Young audiences at European festivals lined up to see pianist Esbjörn Svensson along with bandmates drummer Magnus Öström and bassist Dan Berglund. They even seemed to prefer this band over senior citizen jazz veterans playing the vintage styles from America. In short order, other European jazz ensembles were imitating Svensson’s approach, and even if they weren’t borrowing the specific sounds of EST, they bought into the notion that they controlled their own destiny, and didn’t need to worry about what was playing several thousand miles away at Birdland or the Village Vanguard.

I noticed the change most strikingly when I traveled to England for a jazz conference, not long after the rise of EST. I thought I understood the British jazz scene very well—after all, I had lived and gigged in the UK for two years when I was younger. But something had changed since that time. In a previous day, jazz musicians in Europe would ask me what was happening in the US, but they now showed zero curiosity in this subject. Instead, they wanted to talk about what was taking place in their own world.

And they had plenty to talk about. The first ten years following the rise of EST witnessed a flourishing of local jazz scenes in almost every major city on the continent. Yet even more impressive than the talent, was the level of confidence. A genuine sense of self-determination and homegrown authenticity could almost be felt in the air.

I can’t give Esbjörn Svensson total credit for this. But, even so, I believe that the rise of EST was the tipping point.

Somehow Svensson had found a way to reinvent the jazz piano trio—a formula that was starting to calcify and stagnate in other settings. He had clearly learned from the American masters, but was incorporating all sorts of other influences into the mix.

This started almost from the musician’s birth. His mother was a classical pianist, who loved Chopin and Bach. His father was a jazz fan who listened to Monk and Ellington, and his uncle had been a pianist with a leading Swedish jazz ensemble, Arne Domnerus Orchestra.

Svensson’s studies were tilted toward classical, for the simple reason that he couldn’t always find good jazz teachers. Eventually he confronted the same challenge other European jazz pianists had faced—namely how to deal with the pervasive traditions and expectations of concert hall music that are like a heavy weight on the back of every serious instrumentalist on the continent.

For many European jazz musicians, the response had been to develop a nuanced style of chamber jazz, drawing heavily on local and regional classical music traditions. This approach was legit and persuasive—perfectly suited for performance in the venerable concert halls found in every major city from London to Kiev. The ECM label has made a specialty of this kind of Euro jazz, and for many listeners this is the only kind they know.

But here’s where Svensson’s bio took a detour—one that proved decisive for his later success. After finishing his studies at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm, he gigged with some hard bop bands, but also took jobs with more commercial acts. “I started playing a lot of pop, playing synthesizers and composing pop songs, singing and playing with pop artists.” When he finally returned to jazz, Svensson brought many of these concepts with him. In some ways, a similar shift had happened in the US, where jazz musicians learned from commercial styles, but in America it was almost always rock. Svensson, in contrast, soaked up the very different values of Nordic pop, which gave his music a whole different flavor.

You could hear techno and funk and Bartok and Radiohead in this music. Yet the real breakthrough was that Svensson could do all this without abandoning his commitment to the harmonic and rhythmic complexity of jazz. He had learned a lot from Keith Jarrett (especially the Facing You album) and other cutting edge pianists, and was determined to bring even the most cerebral and sophisticated ingredients into the sound of his trio.

From the outset, I was impressed with how EST could combine these diverse ingredients into a holistic package. The most maximalist acoustic jazz somehow coexisted with minimalist grooves and electronic soundscapes. Sometimes a single composition would move from one approach to another, but it always sounded natural and organic—in a way I had never heard before.

Check out the shifts on “Dodge the Dodo,” which starts and ends with a heavy rock beat, but in the middle (at the 2:55 mark) we get a neo-romantic solo piano nocturne. This makes no sense, either in terms of form or content, but somehow feels absolutely right when you hear it.

Or consider the even more strident shift in “Fading Maid Preludium,” where the opening 45 seconds feature a delicate and translucid solo piano, which suddenly shifts into a loud heavy metal chord. On the other hand “When God Created the Coffebreak” feels just a step away from prog rock at the opening, but two minutes later is mixing in Thelonious Monk and Cecil Taylor.

Who writes music like this? Back at the turn of the century, only one band could do all this, and fill up concert halls along the way.

I suspect that the band’s fluidity in mixing and matching all these ingredients depended, in large part, on their years of relentless performing and touring before their rise to fame. Svensson had known drummer Öström since childhood, and they already had a long history together before launching EST in 1990. Berglund joined on bass in 1993, and they worked as a genuine band—not one of those pick-up ensembles that come and go, so common in jazz—until their breakout success at the end of the decade with a celebrated concert at the Montreux Jazz Festival and the release of From Gagarin’s Point of View.

When success came, EST was ready to flourish as a headline act. Svensson’s pop apprenticeship had also taught him the importance of stagecraft. Unlike most jazz bands, EST often toured with their own sound engineer and lighting designer. The final ingredient, a kind of rock star swagger, came from the musicians themselves—and kept audiences engaged even when the music veered off into deep waters.

The band’s label ACT previously distributed albums in Scandinavia, and EST had already won awards in Sweden, but From Gagarin’s Point of View started selling everywhere in Europe. And a followup release, Good Morning Susie Soho expanded the trio’s audience further. In short order, ACT—previously unknown to me—was emerging as the most creative challenger to the preeminence of ECM on the continent, and with a completely different conception of contemporary jazz.

Svensson deserved a large audience in the US too, and a 2002 tour broadened their following somewhat. But American audiences had very different expectations of jazz back then—the traditionalists had finally triumphed over their adversaries and weren’t ready to embrace jazz music mixed up with dance beats and pop flavorings. The strange thing is that, just a few years later, artists as different as Lady Gaga, David Bowie, and Kendrick Lamar would start incorporating jazz ingredients into their commercial music, but US jazz institutions back in 2002 were still mesmerized by Jazz at Lincoln Center respectability.

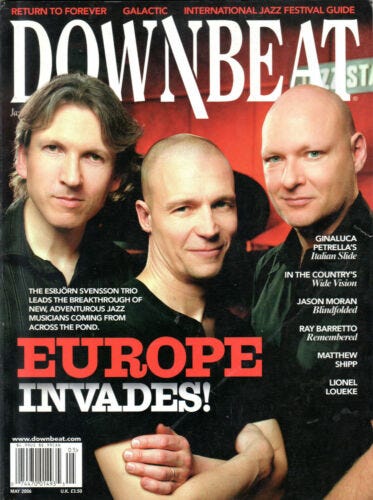

Yet the band’s fame continued to rise in Europe. In 2005, EST’s release Viaticum even entered the pop charts in Germany and France. It rose to number five in Sweden, where it earned platinum status. In the aftermath, Downbeat put the band on its cover—the first time a European ensemble had gotten that treatment in the magazine’s 72-year history—but it was noteworthy that the headline read, in all caps: EUROPE INVADES!

That captured the spirit of EST’s reception in the US all too well. If you were a loyal American jazz lover, you had to choose between repulsing the attack, or getting branded as a collaborator. Or, at least, that’s how it sometimes felt in the circles where I earn my living.

When forced to pick, I decided to join that Euro jazz cult myself. Someone else would need to mount the intervention.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that the jazz trio was getting reinvented back around the turn of the century. The main drivers of this movement were The Bad Plus, Medeski Martin & Wood, EST, and a few other intrepid ensembles. They weren’t ready for jazz to turn into a museum piece, and persisted even in the face of countless articles proclaiming that “Jazz is Dead.” And they deserve some of the credit for the turnaround, circa 2015, when the storyline flip-flopped, and editors started running stories entitled “Jazz is Coming Back.”

But Esbjörn Svensson wasn’t around to enjoy the revival. On June 14, 2008—just a week before EST was scheduled as a headliner at the JVC Jazz Festival in New York—Svensson went scuba diving offshore of Ingarö island, near Stockholm. His companions found him unconscious on the seabed, and though Svensson was airlifted by helicopter to Karolinska University Hospital, attempts at resuscitation failed. He was dead at age 44.

“After Esbjörn’s passing, I made sure all the contents of his computer were saved to backup hard drives,” explains his widow Eva Svensson. “And then I basically left them untouched for the next ten years.”

I don’t need to tell you what a sharp departure this is from standard practice—at least in the US. A music innovator’s archive would be ransacked and monetized before the ink is dry on the obituaries—except when (as is often the case) the heirs engage in legal battles over the money.

But Eva waited until she was ready to confront this legacy from the past. After a decade, she finally took the hard drive to Gothenburg, where she met with sound engineer Åke Linton, who had not only worked with Svensson in the studio, but done live mixing at some 500 EST concerts.

They found the solo piano tracks, which apparently Esbjörn had made, just a few weeks before his death, in the basement of their home. He spent many of his spare hours there—practicing, composing, improvising. Around that time, he purchased some expensive recording microphones, and had learned, with Linton’s help, how to use them effectively.

But the hard drive sat in a cupboard at the Svensson home for a decade. Finally, when she heard the music, Eva knew it had to be released.

“We went to [Linton’s] studio,” she continues. “And we pressed the start button. Then there was a total silence and we couldn't speak for the entire time the music was playing. After it finished, at first we were not able to say anything, because we were both so touched and surprised that it was all there, and that it was so beautiful. The tracks seemed to follow one another like pearls on a string. After we had sat there for a while we agreed: This is really good. Musically, but also from a sound perspective.”

So many posthumous jazz releases are just live concerts with the same songs we’ve already heard before, but this album (entitled HOME.S.) genuinely breaks new ground. Svensson never released a solo piano album during his lifetime, which is odd, because some of the trio’s best tracks featured unaccompanied piano interludes. He was perfectly equipped to perform on his own, and here we finally get a taste of what this might have added to his oeuvre.

I started this article by referring to the initials EST, and their multiple meanings. But I should add that, for me, there’s heavy irony that these initials also stand for Eastern Standard Time—the narrow longitudinal strip that has historically been the epicenter of the jazz world. I take it as another bold, albeit perhaps unintentional, move by Svensson and his cohorts that they could adopt this label even while forcing the jazz world’s awareness on a different part of the world, some six hours ahead of Manhattan.

The whole global jazz scene is on fire right now. London is amazing, Johannesburg is on the rise. I hear stories from Shanghai and Sydney, and many other places. I know that some opinion leaders in the US jazz scene still want to dismiss all this, but it is legitimately the most significant thing happening in the music right now, and may be the calling card of the genre for the 21st century.

Sweden is just a small part of this, but the Nordic renaissance spurred by Esbjörn Svensson and a few others (Jan Garbarek’s name must be mentioned here—but he deserves an essay of his own) did more than anything to pave the way for these later developments. Just as jazz first spread from New Orleans to the rest of the US, it has now found ways to blossom almost everywhere in the world.

Or, put another way, there is no time zone for jazz nowadays. Svensson played a key role in breaking down that barrier, one of the last in the genre’s long history of overcoming limitations. And that’s perhaps the most fitting legacy of all for this artist, whose music itself is timeless.

Lovely piece. Am I allowed to say I like Jazz Sabbath?

https://youtu.be/096Cqsucoy0

Thanks for the endorsement, which led to several hours of enjoyable listening. So far. The music is beautiful and the recording quality is jaw-dropping clear.