How Did Pop Culture Get So Gloomy?

Audiences seek out darkness and dysfunction, but why?

Why did pop culture go over to the dark side?

You can actually measure it in Hollywood box office numbers. The happy genres—musicals, romantic date movies, screwball comedies—have mostly disappeared. But horror and dystopian sci-fi films are more popular than ever.

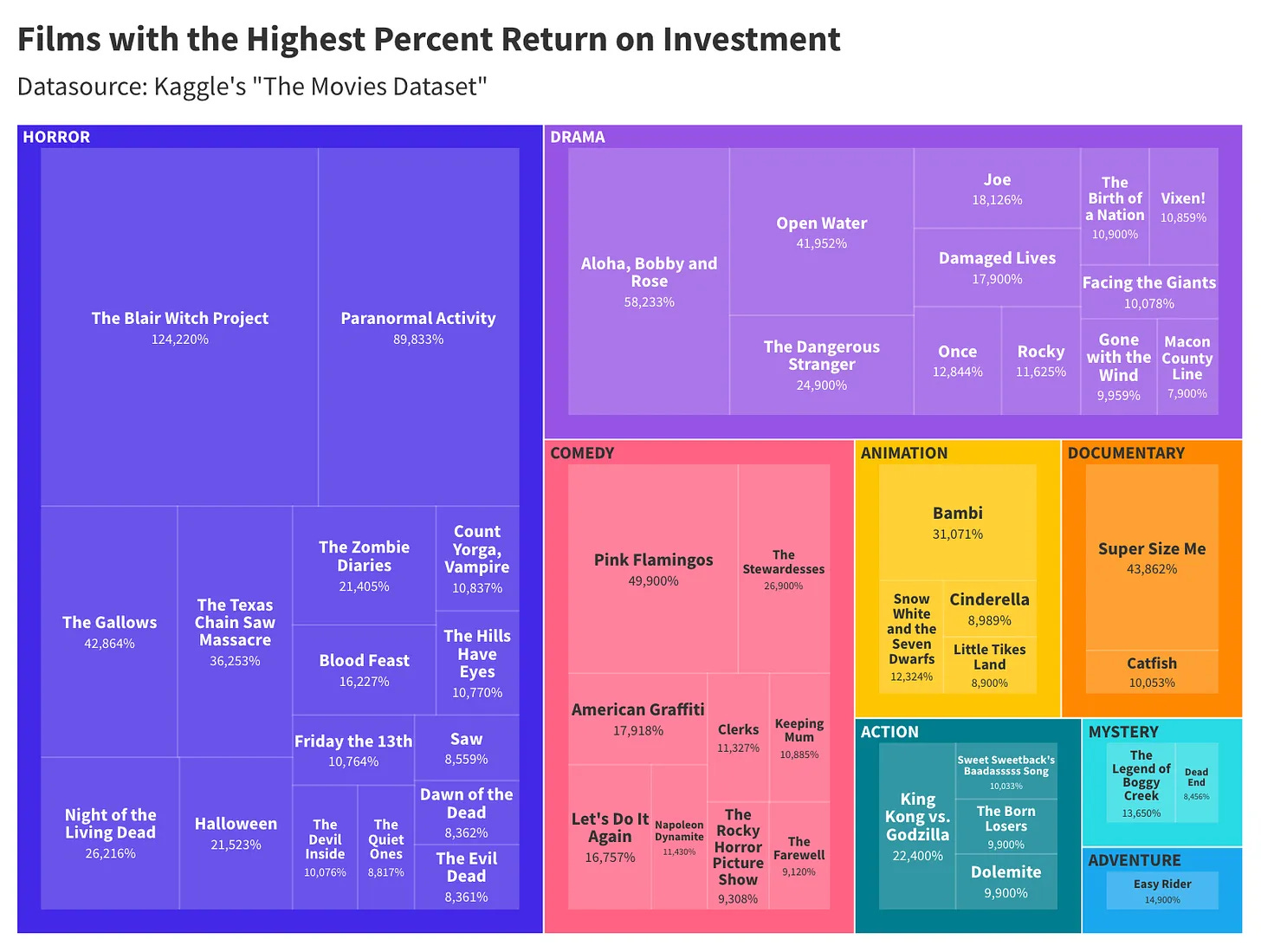

Daniel Parris ran the numbers, and proves that horror offers the best return on investment in the movie business. Audiences don’t want love and laughs—give ‘em slasher films instead.

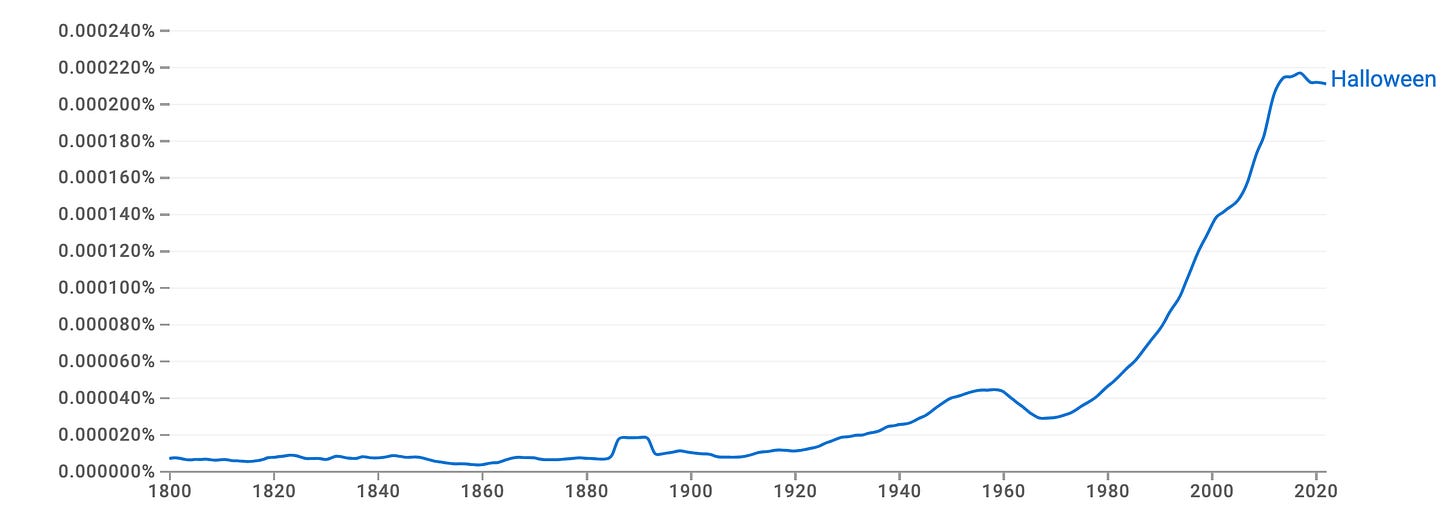

A lot of this is driven by October demand for scary Halloween films. But this, too, is a fairly recent pop culture trend—no holiday has gotten more popular during my lifetime than Halloween.

Not long ago, only little kids participated, but now everybody celebrates October 31 in grand and gruesome fashion—even as other rituals disappear from secular life.

Here’s a measure of the use of the word “Halloween” over time. Are you surprised?

And it’s not just horror movies.

Other film genres now borrow from the horror playbook. Superhero films are filled with scorched earth battlefields. I’ve lost count of the times I’ve seen the Eiffel Tower destroyed (here are a dozen or so examples) or the Statue of Liberty blown to smithereens (see here).

If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (for just $6 per month).

And movie heroes are more damaged than the monuments. Not long ago, Batman was a fun, campy figure. But with each passing decade his psyche gets more broken. The caped crusader is now the most unhinged person in Gotham City.

Well, maybe except for the Joker—who originally operated as a trickster in the mythic tradition, more fun than dangerous. But the Joker is now a nihilist psychopath.

And guess what? The more cruel and inhuman he gets, the more audiences love him. We’ve finally reached the point where the Joker is a bigger screen attraction than Batman—with his own huge move franchise.

Below is a marketing poster for the new Joker film starring Joaquin Phoenix and Lady Gaga—and it sums up the current malevolent vibe in pop culture.

We’ve come a long, long way, baby, from those Doris Day and Rock Hudson romantic comedies of yore. But the pop culture audience today craves darkness and dysfunction.

Now consider the case of James Bond.

In his analysis of modern social pathology, philosopher Byung-Chul Han relies on secret agent 007 as a measure of how playfulness has disappeared from culture.

James Bond movies…have become more serious and less playful over time. The most recent ones even forgo the depiction of rituals of carefree love at the end. The final scene of Skyfall has a disturbing effect in this regard; Bond, instead of dedicating himself to amorous play, simply receives his next assignment from his superior, M. M. says to Bond: ‘Lots to be done. Are you ready to get back to work?’ A stern-faced Bond replies: ‘With pleasure, M. . . . with pleasure.’

The irony, here, is that pleasure is notably missing from this entire sequence. James Bond has somehow turned into a stoic workaholic.

I admire actor Daniel Craig as James Bond, but how did we get from the Dionysian secret agent, with his intoxicants and fertility rites, to this grim Apollonian, who doesn’t even care if his martini is shaken or stirred?

“The culture is not just an effect—it’s also a cause.”

I know stoicism is a hot trend in the culture right now—take a look at the bestselling philosophy books on Amazon and see for yourself. But can’t we let 007 have a little fun?

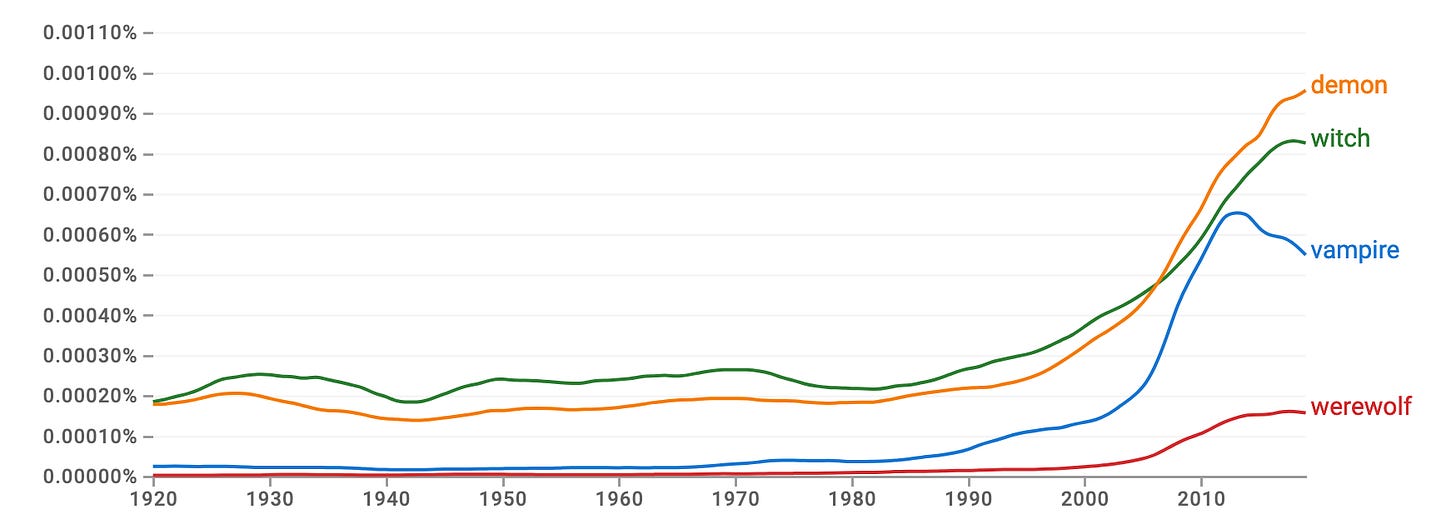

It’s not just movie franchises—the same thing is happening with books. We live in an era of rationalism and science, but that’s not what people want to read about. This chart shows the increasing use of some supernatural words over the last century.

And what about music?

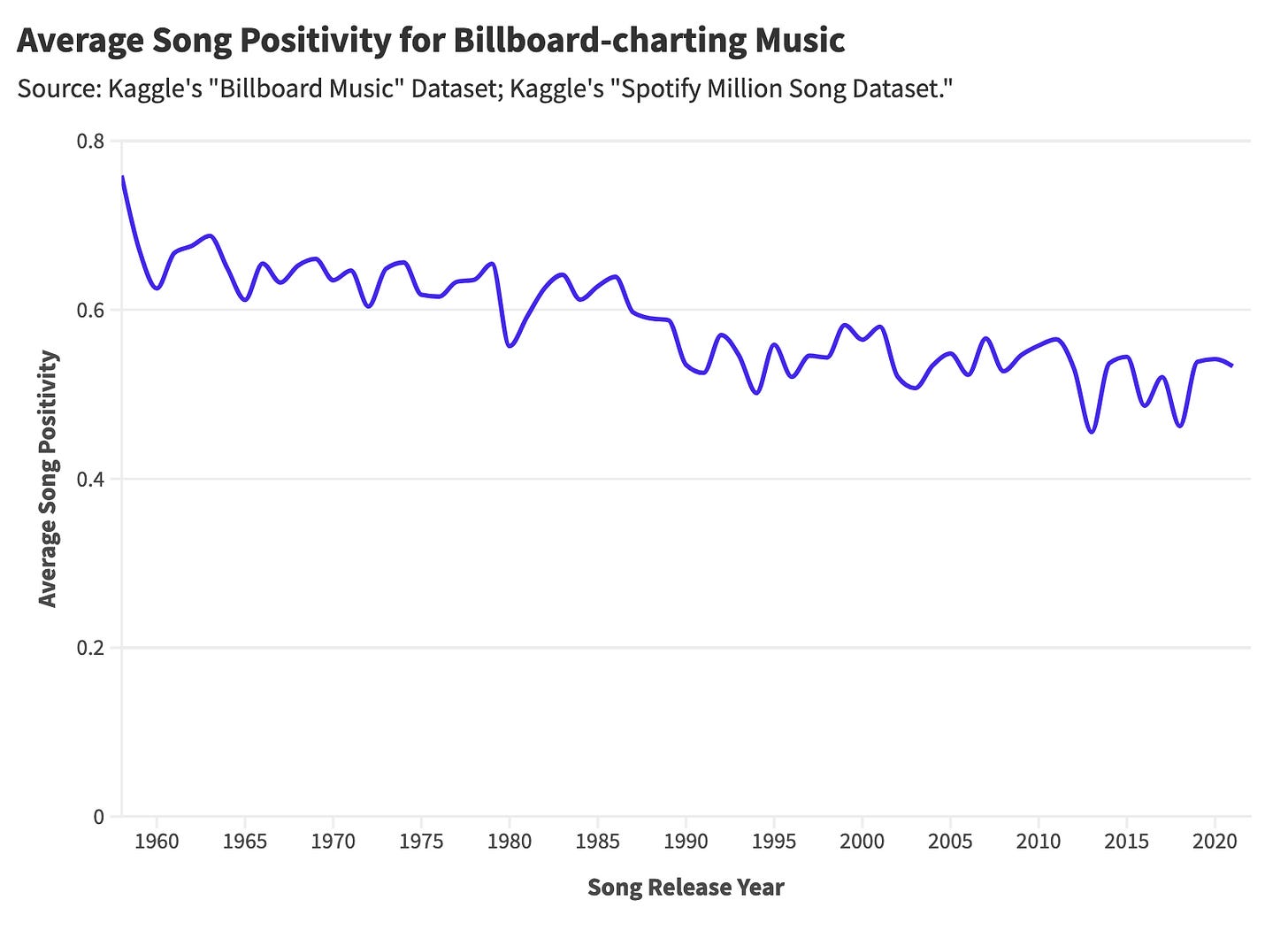

Here, too, I consult data guru Daniel Parris—source of the chart on movies at the top of this article—who is a whiz at tracking cultural trends. He provides me with this timeline of positivity in hit songs since 1960. (He shares other longterm song metrics in a recent article, which I highly recommend.)

According to this metric, a song is positive if its is “happy, cheerful, euphoric,” and is negative if it is “sad, depressed, angry.”

That’s a long sad slide.

Why are these trends all converging on negativity? What does this tell us?

Popular culture always reflects the larger social reality. I’ll even go further, and claim that pop culture is our single best source of information about the psychological state of society. In some odd way, the revolution is televised—it emerges in songs, films, and other forms of entertainment long before the political leaders even notice.

Rock music anticipated the social changes of the 1960s by several years. The same thing is true of jazz in the 1920s. And the Viennese waltz played a similar role in 1800. Troubadour songs did the same back in the medieval era.

You can actually watch social values toppling on the dance floor.

So I can only conclude that the grimness and negativity in our popular culture is a mirror of the audience.

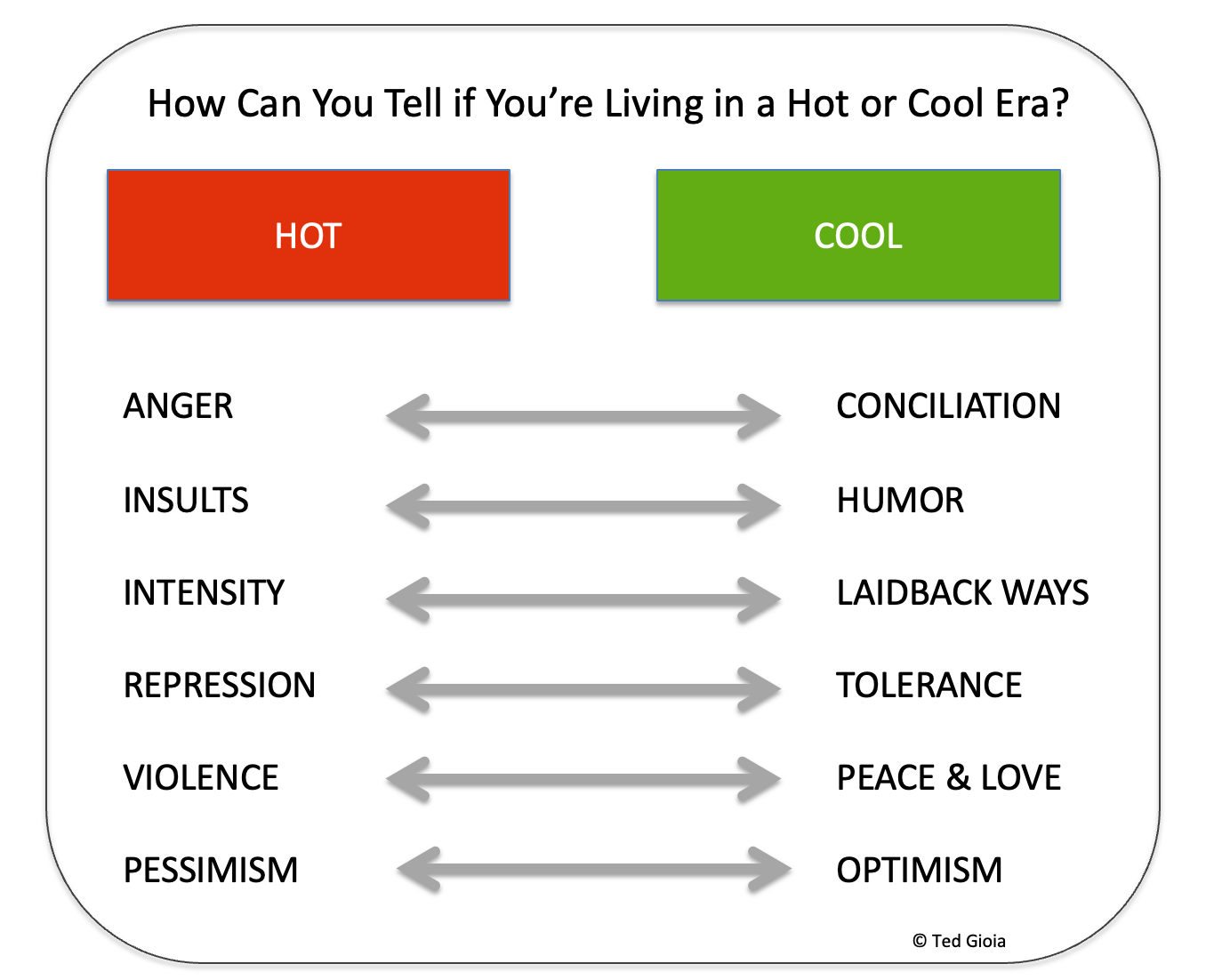

But that shouldn’t be surprising. I’ve written elsewhere about our cultural shift from cool to hot, and how it’s disrupting social stability. I’m certain you’ve noticed it too, by now.

And when we looked at dopamine culture, we saw how web platforms obsessed with delivering pleasurable stimuli actually create anhedonia—namely the opposite of pleasure. And this is supported by survey data, especially surveys of teens and young adults.

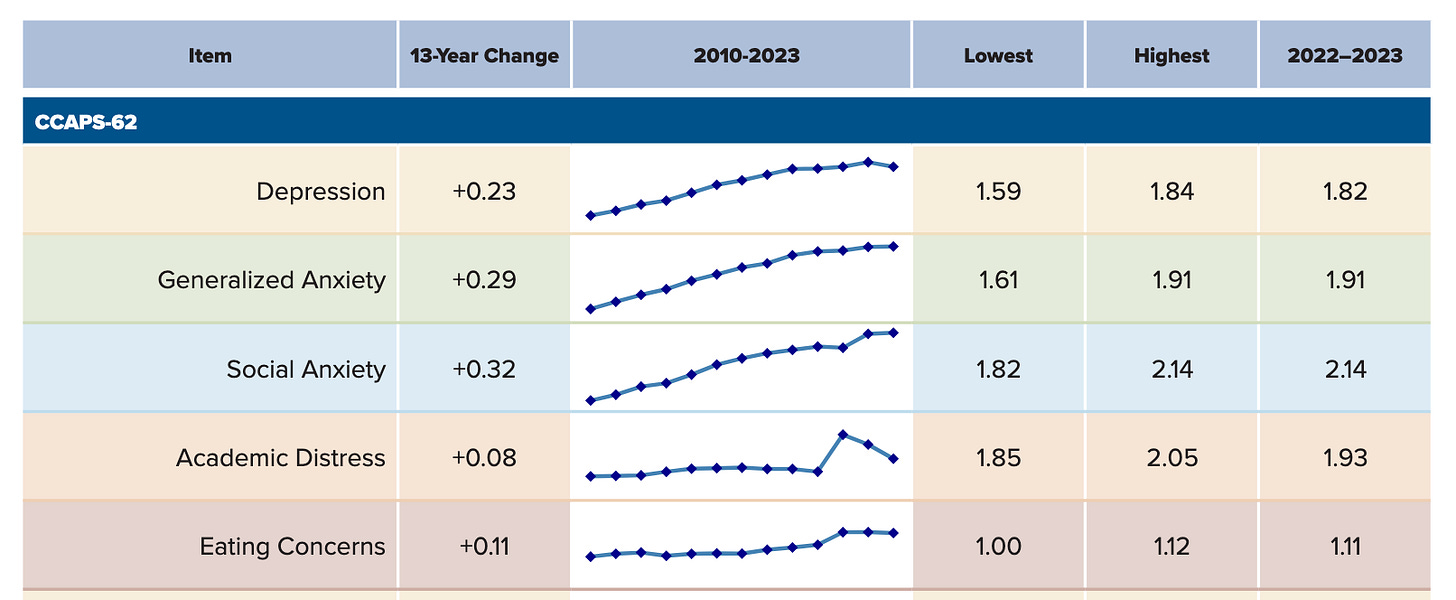

Below are metrics on the mental health of college students. Note that they worry less about grades, but more about everything else.

Anxiety and depression are now twice as common among students as concerns about academics or relationships.

Don’t expect more positivity in popular culture until we reverse these trends. But we might have already created a vicious circle where a bleak society leads to gloomy songs and stories, which further amplify the depression and desolation.

In other words, the culture is not just an effect—it’s also a cause.

If that’s true, the people who have the most responsibility here are entertainment execs as well as technocrats who run the main cultural platforms—TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, etc.

Their algorithms and addictive interfaces are literally the growth engines for dysfunction. They amplify it, they disseminate it, they help it go viral.

But, of course, these same algorithms (and the organizations that control them) can also help turn the tide.

The first step, of course, is admitting that there’s a problem. I can see it, and you surely can too. It would be nice if the business insiders who enrich themselves from this mess would also come clean—and admit what’s already obvious to the rest of us.

Once that happens, there are many ways to fix these problems.

The decision-makers who control pop culture might actually benefit from a reversal. I suspect that the level of depression and dysfunction in society at large is causing people to detach themselves from media and entertainment.

In other words, healing psyches might be a good business move, and not just a good deed.

But what if the corporate leaders who let these genies out of the bottle fail to take action?

In that case, we may need to force their hands. There are ways for doing that, too.

Fascinating.

I’m used to railing about society being taken over by a Malthusian death cult, but this is a refreshing and well-balanced take haha.

I know a number of people who are genuinely good people, but they have adopted the idea that having children and a family is a burden on the planet, and that humankind is ultimately a net negative for the planet. A very strange take for a human being to have…

If people start off with that kind of dark axiomatic worldview, the rest is all just a logical consequence of that closed system thinking.

Over the last decades, our society has been conditioned to think in terms of closed systems and scarcity, despite the fact that life and the universe, and human creativity, suggest the universe is fundamentally characterized by open systems and an abundance of creativity.

The 1958-63 era of those Rock Hudson/Doris Day movies was also the era of atomic doom movies like Doctor Strangelove and On the Beach, as well as an endless string of monster movies like The Blob. And the early James Bond movies were thick with cynicism and nihilistic violence. I won’t disagree that the present moment is dark and grim, but there’s a lot more going on here than a simple duality.