How Christopher Burney Discovered Mindfulness in a Nazi Solitary Confinement Cell

The captured British spy later declared that his 526 days in isolation were "an exercise in liberty"

Many books have been written about the joys of the contemplative life. But I only know of one written by a prisoner in solitary confinement.

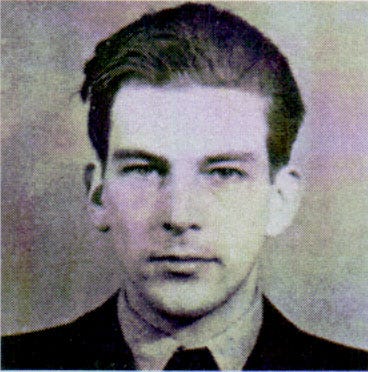

Christopher Burney (1917-1980) had it worse than almost any inmate today. Captured by the Nazis in occupied France, and held in Fresnes Prison, he survived on a single daily bowl of watery soup with a little bread—and even that was taken away sometimes in punishment.

His tattered blankets offered little protection against the cold. At one point, guards even removed his thin mattress, forcing him to sleep on the stone floor.

But worst of all, Burney constantly feared torture and execution.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Burney had operated as a British spy behind enemy lines, and knew secrets that could endanger the lives of colleagues. When he heard footsteps outside his cell, he feared that the deadly moment had arrived. Authorities had come to interrogate him with all the brutal tools of their trade.

Survival was unlikely. Once he had told them everything he knew—and how could he avoid it when tortured?—he would certainly be executed for espionage.

This is the setting for Burney’s book Solitary Confinement (1951), one of the great masterpieces of contemplative literature.

The book is out-of-print and hard to find today But that tells you more about our narrow pop culture concepts of heroes. They’re supposed to fight Nazis like Indiana Jones, with fancy tricks and special effects—not practice mindfulness in a cold, dank cell.

In fact, I’ve only encountered one serious appraisal of this book, from literary critic Frank Kermode. But he understood how valuable Burney’s testimony was. “The courage and the intellectual integrity of this writer,” Kermode declared, “are far beyond what most of us would expect of ourselves.”

More to the point, Burney gave a stirring example we can learn from today—and without undergoing the risks and stresses of 526 days in an isolation cell.

In the early days of World War II, Burney served as a lieutenant in the British Army before getting enlisted for a dangerous spy mission. He wasn’t especially brave or tough, but was recruited for his commando training and, especially, his mastery of French. He spoke the language fluently and idiomatically, with no accent.

Assigned a new identity as “Charles,” Burney parachuted into the French countryside on May 30, 1942. He tried to rendezvous with resistance groups working to destabilize Nazi supply lines. But one of his trusted contacts, Mathilde Carré, worked for the Germans as a double agent.

Because of her betrayal, Nazi authorities tried to arrest Burney almost from the moment of his arrival in France. But he shrewdly identified the police stakeout at his first appointment with the French underground, and went on the run.

The Nazis pursued him relentlessly. They even sent a warning letter to hotel workers and bank employees, which included a good description of the spy—tall, fair-skinned, and looking very British. With his cover blown, there was no safe place to hide.

Burney tried to escape across the Pyrenees to Spain, but didn’t get that far. Instead, he was arrested in the middle of the night, after a hotel clerk tipped off German intelligence. Soon afterwards, he was locked up in solitary confinement at Fresnes—where he spent the next 15 months.

Most of our other great works about the contemplative life are written by monks and mystics. But Burney was a young, active man in his mid-20s, and totally unprepared for a life of isolation. He wasn’t especially religious or philosophical, and had few intellectual resources to fall back on.

The interrogations did not begin for several weeks. But hunger and cold threatened to kill him before the Nazis got around to it. He tried to treat his tiny food ration as a three course meal—but it wasn’t easy:

“I took the soup slowly, drinking the water first and eating the questionable solid afterwards, pretending in this way that it was a meal of two courses….

“To keep my bread untouched was always difficult, and the more so as time went on and I became chronically hungrier, but I decided that it was the best course. For there were ten hours during the night during which nothing could happen, nothing be done except lie in bed, and to pass them awake and on an empty stomach was an ordeal which was best avoided….I hid the crust under a blanket, or even under the bed, and tried to convince myself that it was not really there.”

The day of interrogation finally arrived, and Burney amazed himself by his ability to construct an intricate series of lies and alibis. He even signed a confession, but it was filled with bogus details.

For a while this kept him alive, but soon authorities higher up the command chain decided he had lied, and brought him in for more questioning. Again he exercised his ingenuity and somehow managed to avoid execution, month after month, without betraying his friends. But he was always at risk.

The biggest challenge was just filling up the hours while awaiting an uncertain fate.

Burney later claimed that he would have welcomed insanity, as a kind of escape. He even tried to lose his wits, but such things are not matters of choice. Instead he stayed coldly rational—and was forced to devise some meaningful daily routine with almost no resources at hand.

I’ve written elsewhere of the remarkable powers of rhythm and music, which are sadly underappreciated in our society today. We use songs for entertainment and diversion, when they can offer so much more. Burney also came to this realization, but through sheer necessity.

But he wasn’t a musician. And there were no songs to hear. So how could he tap into this power?

“He finally found that a patterned beat, much like the time signature in a composition, offered the greatest source of relief.”

Burney writes:

“I embarked on a musical program to conclude [each] day. Being no singer, even to my own taste, I whistled every tune I could remember, the martial ones to make me triumphant over my enemies, the homely ones which made me think of food, and the emotional ones which occasionally, and to my own amusement, brought a conventional tear out of its duct.

“This was a long program which grew as my memory became sharper and it brought me easily to a point where I could say, ‘Now it doesn't matter if I do eat my bread.’ And, having reached this point, I found it easy to go on almost forever….”

Yet this was a risky practice—because music of any sort was forbidden at the prison:

“Once or twice my performances were interrupted by the entry of an infuriated sentry. Our regular guards never worried over such details, but the mean substitutes who replaced them at weekends could only use petty excuses to intrude upon us.”

But even without music, Burney found tremendous comfort in rhythm.

Like so many prisoners, he resorted to pacing. He didn’t have much room to operate, and experimented with different ways of navigating through his 10 X 5 foot cell. At first he thought that walking in a circle would give him a greater “sense of liberty”—and even pushed his bedding up against the wall to make space for a tiny round pathway. But he finally found that a patterned beat, much like the time signature in a composition, offered the greatest source of relief.

“The experiment proved that the most satisfactory method was to go straight up and down, taking five paces from end to end and pivoting round on the last in such a way as to keep the rhythm even. It was strangely calming and absorbing….The motion and sound became hypnotic, like the drip of water or the pulse of a drum.”

He now had a suitable pace. And he also had a kind of clock—really just a moving shadow on the wall, but it allowed him some way of measuring the passage of the day. But he also needed something to feed his mind.

Anything he could summon from memory was a treasure—a few lines of a poem, a recollection of a good meal, a proverb or literary passage, or some other tidbit from the past. Sometimes he would set himself arbitrary tasks—trying, for example, to list the counties in England and Scotland, or the states in the US. Or he would pick two cities and imagine a journey from one to the other, identifying all the people and places along the way.

But, even better, the guards occasionally gave Burney some scraps of paper. He paid the closest attention to whatever was written on them, even if it seemed useless.

“My paper ration one day produced the last few pages of a book by Sir James Jeans on Planck’s Constant, translated into French; and although physics had never reached such a level in my world, I was able after many days of concentration to understand the argument, which, I imagine, was set out for novices.”

But over time, Burney managed to reach some higher realm of contemplation. This is perhaps not surprising—philosophers as great as Socrates and Boethius found inspiration while awaiting execution. What makes Burney’s case so fascinating is that he was not a trained philosopher or scholar of any sort.

Yet he now embarked on detailed meditations on the great problems of human existence. He explored the paradoxes of free will, the nature of individual responsibility, the dualism of soul and body, and other issues that a philosophy grad student might examine. But in Burney’s case, he had no teacher or texts, merely his own intellectual resources and dogged persistence, fueled by the empty hours.

He shares many of his musings in Solitary Confinement. Sometimes the results are impressive. For example, he dug deeply into the nature of evil—something that a prisoner held by Nazis would inevitably think about. This issue has bedeviled the greatest minds since the earliest days of rational speculation, and Burney came up with a theory surprisingly close to what Boethius had concluded in his own prison cell back in 523 A.D.

Just as light possesses power, and darkness is merely its extinction, so too does good contain an active energy that evil can never match. On this basis, Burney abandoned the conventional view that good and evil were polar opposites—instead adopting a scale in which “only positive degrees of good” had meaning and efficacy. This allowed him to accept everything with an embracing mindset of optimism—"the good in life,” he declared, “is no longer overshadowed by its imperfections….The tiniest window bringing light will always dominate the bleak and oppressive walls.”

By the time he reached the end of his stay in Fresnes, Christopher Burney had achieved a state of inner peace he would have hardly thought possible at the outset. These many months of solitary confinement, he eventually decided, were “an exercise in liberty.” They had allowed him to “scan the horizon of existence" and he had received glimpses of an enlightenment "behind the variety and activity of life." This kind of hard-won serenity would have never been granted him in more comfortable settings.

“Solitude,” he concluded, “is liberty indeed.”

Perhaps others have reached the same conclusion, in some retreat or hermitage. But few have done so in such a dire situation, and with so many threats hanging over their heads. If mindfulness is possible in those circumstances—with so little to see, touch, hear, or taste—imagine what riches it can offer to us, with the whole world at hand.

thanks for this. several copies of the book are available for free on Internet Archive if anyone is interested. Reminds me of Victor Frankl.

When I was in my 20s and 30s, I practiced aikido about 15 hours a week. One day when I was 25, I met a doctor from Vietnam maybe 20 years older than me, who was delighted to hear that I did that. He said, "Aikido helped me survive a prison camp!" This astonished me a bit, until he explained. Aikido (correctly instructed) had taught him mindfulness and to think only about the next thing he had to do. His explanation matched that to be found from Victor Herman in his book "Coming Out of the Ice". Herman was an American who went to Russia to work at a plant that Ford built for Stalin, and like almost all his colleagues, landed in the gulag, but was one of the few who survived. Very much like the Vietnamese doctor told me, he wrote that the key to survival was to focus only on the next thing to be done. Herman said that many literally worried themselves to death in the gulag thinking about their past, their future, etc.

"Coming Out of the Ice" is a powerful memoir that was taken off the market when it was high in the bestseller lists, apparently because the New York publisher had gotten a deal to publish Brezhnev's autobiography if they pulled Herman's book off the shelves. He found a large stock of them still unsold somewhere and sold them from his home until they sold out, and then the book was republished by a company somewhere in the Plains states. It has also long been out of print, and used copies of the paperback go for $300 on Amazon, and the hardcover goes for over $500.