How Bing Crosby Made Silicon Valley Possible

The singer who popularized "White Christmas" was also a visionary tech innovator

I.

Bing Crosby was the most successful entertainer in the world during the first half of the 20th century. He rose to the top in everything he tried his hand at—records, movies, radio, live performances.

He even defined a new cultural tone, which people called ‘cool’.

I once heard a music critic describe Crosby at his peak as the coolest white man on the planet. That’s not a bad way of conveying his appeal. Cool started out as a jazz style, but Crosby turned it into a consumer lifestyle.

By the 1950s, everybody in America wanted to be cool.

But Crosby showed how it was done back in the 1920s and 1930s, mastering a panoply of attitudes that emphasized his relaxed, laid-back persona. It shaped everything, from his way of speaking to how he walked and gestured. And especially how he sang.

Few people know how much Crosby’s coolness depended on technological innovation.

Holiday subscriptions to The Honest Broker are now available.

His impact as a technologist was just as great—maybe even greater—than his influence as an entertainer. At several key junctures in his career, Bing embraced an new technology, and revealed its potential in ways that changed the course of entire industries.

During the 1920s, microphone and amplification technologies made huge improvements, and Crosby understood better than any other vocalist what these new developments meant. Previously star singers had learned to project their voices as loudly as possible—they needed to do this to reach listeners in the back of the theater or concert hall.

Bing Crosby changed all that.

Before Crosby (let’s call it B.C.), the more famous you were, the louder you had to sing—because your audience was so large. (Opera still bears the lasting mark of that rule.) But after Bing, the exact opposite was true. For the first time, a skilled vocalist could entertain a huge crowd, but still sing in an understated, conversational manner.

But few singers understood this at first. Most considered microphones as a tool for amplification, not a pathway to a different way of singing. And even those who grasped the potential were often unable to take full advantage of it—doing so required them to re-learn all the basics of their craft, from melodic phrasing to syllabic enunciation.

Crosby showed them how it was done. While others struggled with this technological step-change, Crosby completely rewrote the rule book for popular and jazz singing. We’re still dealing with the consequences today. In fact, you could draw a straight line from Bing Crosby’s “Mary” to Billie Eilish’s “Bad Guy.”

This created a revolution in the music business. They called this new low-key style “crooning.” And no crooner was more popular than Bing Crosby.

Just consider the number one hits he enjoyed in the 1930s. Below are the songs he recorded that climbed to the top of the charts, followed by their weeks in that position.

Other singers learned from him, even the greatest. Just compare how Louis Armstrong’s singing evolved between the late 1920s and early 1930s.

In Armstrong’s 1926 performance of “Georgia Grind,” he sings a saucy love song with his wife Lil Hardin Armstrong—but the vocals are so powerful, it sounds like they’re having an argument. But after the crooning revolution, Armstrong became one of the most flexible and nuanced singers on the scene. Compare, for example his delivery of “I Surrender, Dear” from 1931.

The love song had now achieved an intimacy it had never possessed before (at least not in public performance), and Crosby led the revolution—but only because he understood the potential of the latest technology. Other crooners, for heaven’s sake, were trying to sing out of megaphones.

II.

Just a decade later, Crosby launched another technology revolution in entertainment. And this time he helped create Silicon Valley.

I’ve written elsewhere about the strange ways in which music made Silicon Valley possible. But Crosby’s role in the rise of Ampex is the most fascinating chapter in this story. Ampex revolutionized data storage—the cornerstone of the tech revolution—but only because a famous jazz singer felt overworked, and needed a way of pre-recording radio shows that sounded as good as live broadcasts.

That singer was Bing Crosby.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out paid subscription.

Crosby felt exhausted in the mid-1940s. And who could blame him?

Bing was the most popular musician in the world—and it wasn’t just “White Christmas,” which sold more records than any other song in history. He eventually recorded more than 1,600 songs, and more than forty of them reached the top of the chart. But he was just as popular in movies, winning the Oscar for Best Actor in 1944, and getting nominated again in 1945. During that same period, Crosby was tireless in touring and entertaining troops overseas.

But it was his radio show that proved to be too much.

Because of the time difference, Crosby had to do two different live broadcasts—and the network refused his proposal that they pre-record the later West Coast show on 16-inch transcription disks, basically a very large phonograph record. NBC had good reason for this. The sound quality on the disk recordings of that day was noticeably inferior. And the disks were cumbersome to edit—negating one of the major advantages of pre-recorded shows.

Crosby needed better recording technology. And in 1947, a stranger from Northern California made the trek to Hollywood with a big box that not only solved Bing’s dilemma, but set the wheels in motion for a whole host of later innovations.

What Jack Mullin did at MGM Studio that day is almost like a magic trick. He set up a live performance behind a curtain, and then followed it with a playback from his magnetic tape recorder. The audio quality was so true-to-life that many listeners couldn’t tell the difference. A private demonstration was arranged for Crosby at the ABC Studio on Sunset and Vine.

Crosby knew immediately that this was a huge breakthrough. But the price of a single Ampex 200-A machine was $4,000—more than many people paid for a home back then. In fact, the average median family income in the US that year was just $3,000. But Crosby wanted to buy 20 of these machines. He offered to pay 60% of the money up-front.

Thus, a few days later, a letter arrived in the Ampex office with a Hollywood postmark. Inside was a check from Bing Crosby for $50,000.

III.

The whole story begins with a mystery about Nazis.

Long before he became chief engineer for Bing Crosby Enterprises, Jack Mullin was a major in the US Army Signal Corp, who spent a lot of time listening to Nazi radio broadcasts during World War II. Unlike his colleagues, Mullin was puzzled by the classical music he heard coming out of Germany—it sounded like live performances by orchestras, but somehow he doubted that the Berlin Philharmonic was really giving a concert so late at night.

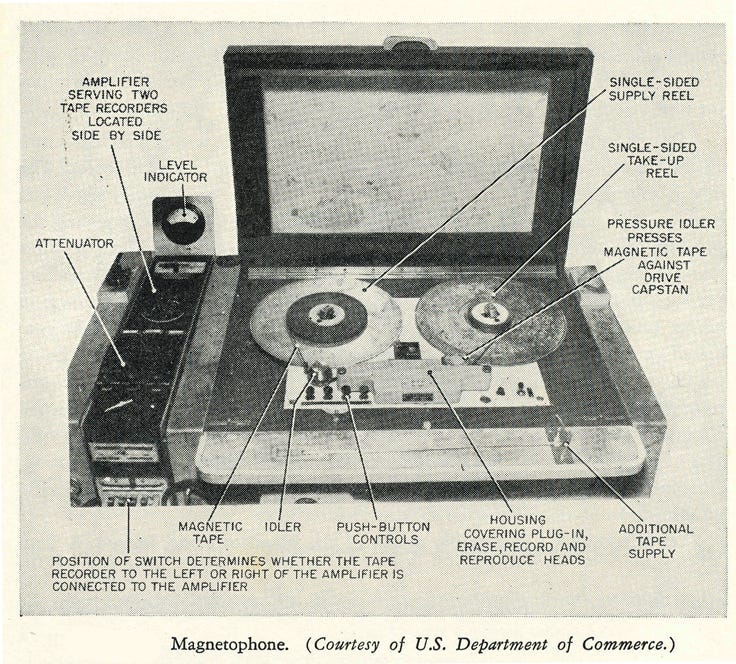

After the end of the war, he solved the mystery. The army sent him to Germany to document their electronics technology, and he discovered magnetic tape recorders. This device, known as the Magnetophon was even used by Hitler to pre-record speeches, which could later be broadcast on the radio as live announcements.

Mullin returned to California, after the war, with two of these tape recorders, and plenty of tape, along with instruction manuals and schematic drawings. His goal was to create his own tape recording equipment with American parts.

On May 16, 1946, Mullin gave a demonstration of German Magnetophons at the NBC Studio in San Francisco. The buzz it created soon led to the launch of Ampex.

The tape recorder may not seem like a high tech device, but tape storage existed before disk storage, just as disk storage happened before cloud storage. And they all trace their origins to Thomas Edison, whose invention of the record player and motion picture were actually solutions to data storage problems.

Few people today understand how advances in data storage have always been linked to music and movies. Long before personal computers appeared on the scene, the entertainment business funded these tech innovations. Even in recent time, streaming tech was bankrolled by music and movies.

Crosby is a major figure in this story, perhaps the most important of all.

Ampex, launched in San Carlos, California in 1944 is the key connecting point between music storage and data storage. That tiny startup, according to Silicon Valley historians Peter Hammar and Bob Wilson, was involved directly or indirectly in the launch of “almost every computer magnetic and optical disc recording system, including hard drives, floppy discs, high-density recorders, and RFID devices.”

Crosby himself moved to Silicon Valley in 1963, buying a home in Hillsborough for $175,000. (The house was recently listed for $14 million.) According to his son Nathaniel, Crosby and his wife Kathryn didn’t want to raise their children in Hollywood. A few months later, they moved to an even larger house on the other side of town.

By any measure, Bing Crosby’s life was an amazing success story. And he understood the financial upside enough to become a West Coast distributor for both Ampex and 3M magnetic tape. But if he had taken equity positions in Silicon Valley startups, instead of just financing them as a customer and distributor, he might have become the godfather of high tech—and the Crosby family would be on the Forbes billionaire list today.

Maybe even at the top of the list.

IV.

Just consider some of the long-term results of the magnetic tape revolution in entertainment—not even including what this storage tech did for personal computing.

After the introduction of magnetic tape, radio and TV shifted from live entertainment to pre-recorded shows. That’s now the model for almost everything you watch on a screen, from Netflix to YouTube.

Crosby’s advocacy of tape made it possible to edit music and broadcasts—which was almost impossible previously. You could even call him the originator of cut-and-paste.

Sound quality improved dramatically with the introduction of magnetic tape. The whole high fidelity revolution grew from this starting point.

The videotape recorder was developed at Ampex (by Ray Dolby), thus facilitating the widespread dissemination and preservation of film and television programming. Even today we “push play” to start online videos—much like the first users of Ampex tech.

Many other ingredients of entertainment that we now take for granted came out of the tape revolution—encompassing everything from the ridiculous (the laugh track on TV shows) to the profound (multi-tracking in the recording studio).

I like to imagine what else Bing Crosby could have done in Silicon Valley in the 1960s and early 1970s, if he hadn’t been spending so much time on the golf course. Crosby wasn’t afraid to make risky investments. In 1948 he became a major investor in Minute Maid, which introduced concentrated frozen orange juice to the mass market. He was also one of the owners of the Pittsburgh Pirates, and made various oil and real estate investments on the West Coast.

Under slightly different circumstances, he could have established the venture capital model that now pays most of the bills in his old Hillsborough neighborhood. Bing had the vision—he had proven on two momentous occasions that he understood how tech could change the world. He also had cash to invest, and was now on the scene in Silicon Valley to put it to work.

Why didn’t he do so?

My hunch is that he was just too cool. You need to be more intense to end up like Steve Jobs or Mark Zuckerberg or Bill Gates. But Crosby was out playing golf and joking with his friends, when he wasn’t flying down to Hollywood to make a movie or TV appearance.

Truth to tell, Bing Crosby didn’t need more money or a tech empire. But we might all be better off, if people with his cool cultural acumen had made the key decisions on tech platforms. He made singing more nuanced and aligned with people’s feelings. Wouldn’t it be great if he had done the same thing with Silicon Valley?

Fascinating, but you're leaving out something:

Because "Crosby couldn't bear to watch [Game 7 of the 1960 World Series] live, although he did listen by radio while in Paris,... he had hired a company to record the broadcast by kinescope. The early relative of DVR meant that he could go back and watch the 2-hour, 36-minute game later if the Pirates won." This tape, found in his wine cellar, whose conditions preserved it, is the only video of Mazeroski's series-winning home run. See https://www.espn.com/mlb/news/story?id=5611152

Of course, his son said he abused his children so viciously two committed suicide. He should be remembered for that as well.

This had to be one of Ted’s most engaging post ever. Thanks, Ted.