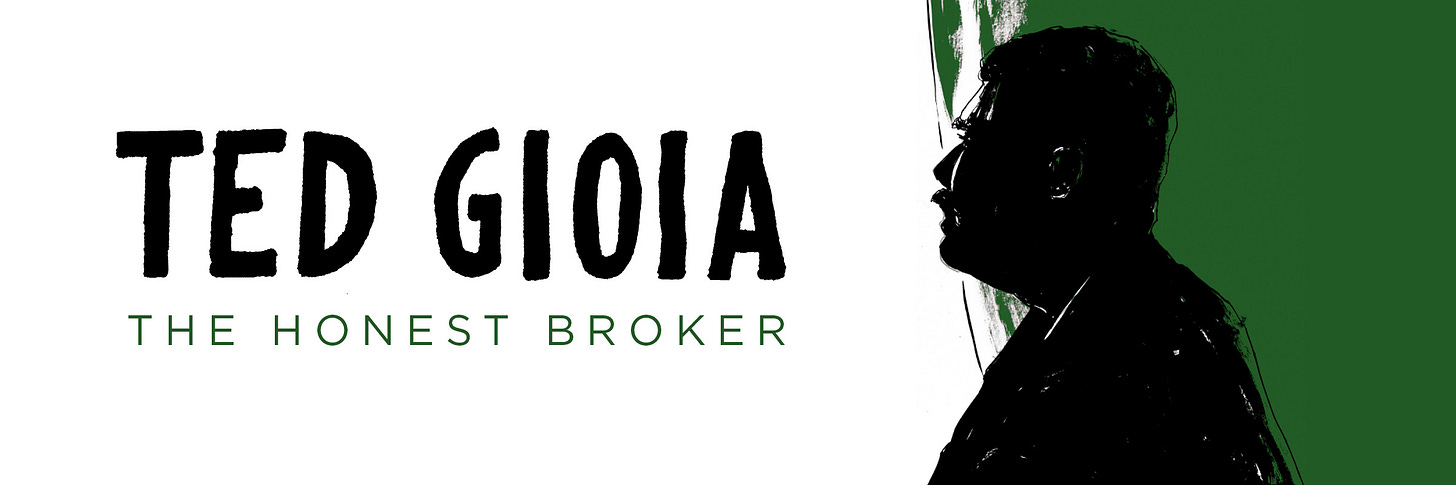

How an Angry Woman in Baltimore Almost Killed the Jazz Age

When Mrs. Martha Lee went to war against jazz (1922)

Jazz is painfully respectable nowadays.

I know horn players who have CVs longer than CVS receipts, and hang out at the faculty club after the gig. At this rate, the next generation won’t release an album until it goes through IRB and passes double-anonymized peer review.

But it wasn’t always that way.

A hundred years ago, jazz was under attack from all directions. Everybody from parents to politicians to the Pope tried to stop it.

But they hated jazz especially in Baltimore. And it was mostly because of one woman—Mrs. Martha Lee. She went to war against jazz in 1922, and tried every trick imaginable to kill it.

Mrs. Lee and her supporters even dreamed of a new Prohibition—when jazz ballrooms would be shut down, much like the recently banned taverns and bars.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

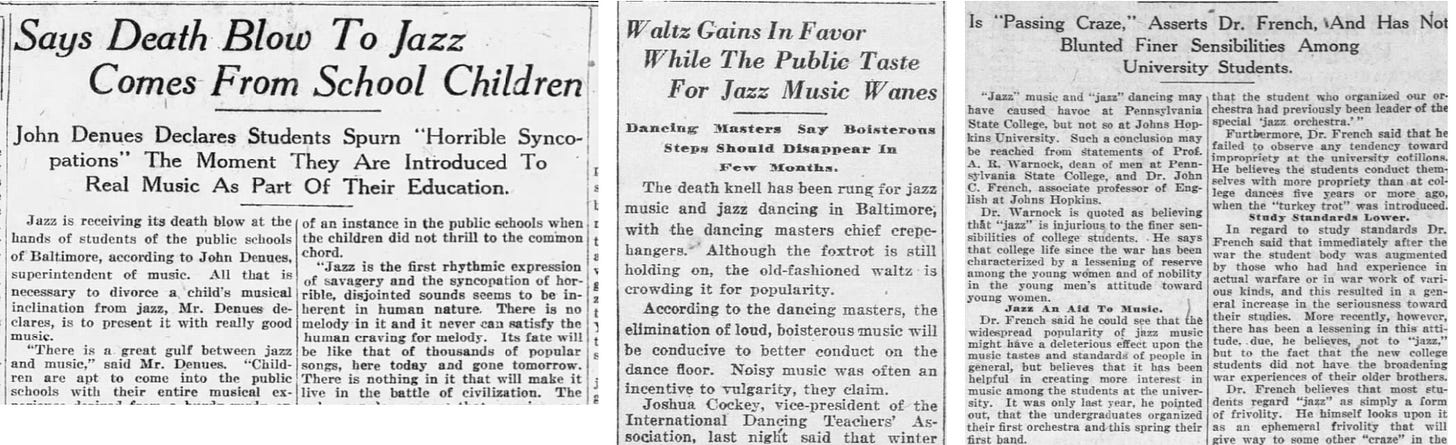

News coverage of jazz in Baltimore until that time had been skeptical, but the general assumption was that this ugly trend would soon end.

But late in 1921, newspaper coverage of jazz became shrill and panicky. The experts had been waiting for jazz to die—but instead it got livelier and livelier.

A few journalists even started mocking these smug obituaries for hot jazz. An anonymous Baltimore columnist wrote:

We observe that jazz has died again. One of our worthy dancing masters, just returned from the annual convention of the American National Association of Masters of Dancing, announces the demise.

Alas! We have our doubts….We decline to serve as honorary pallbearer until somebody produces and identifies the corpse.

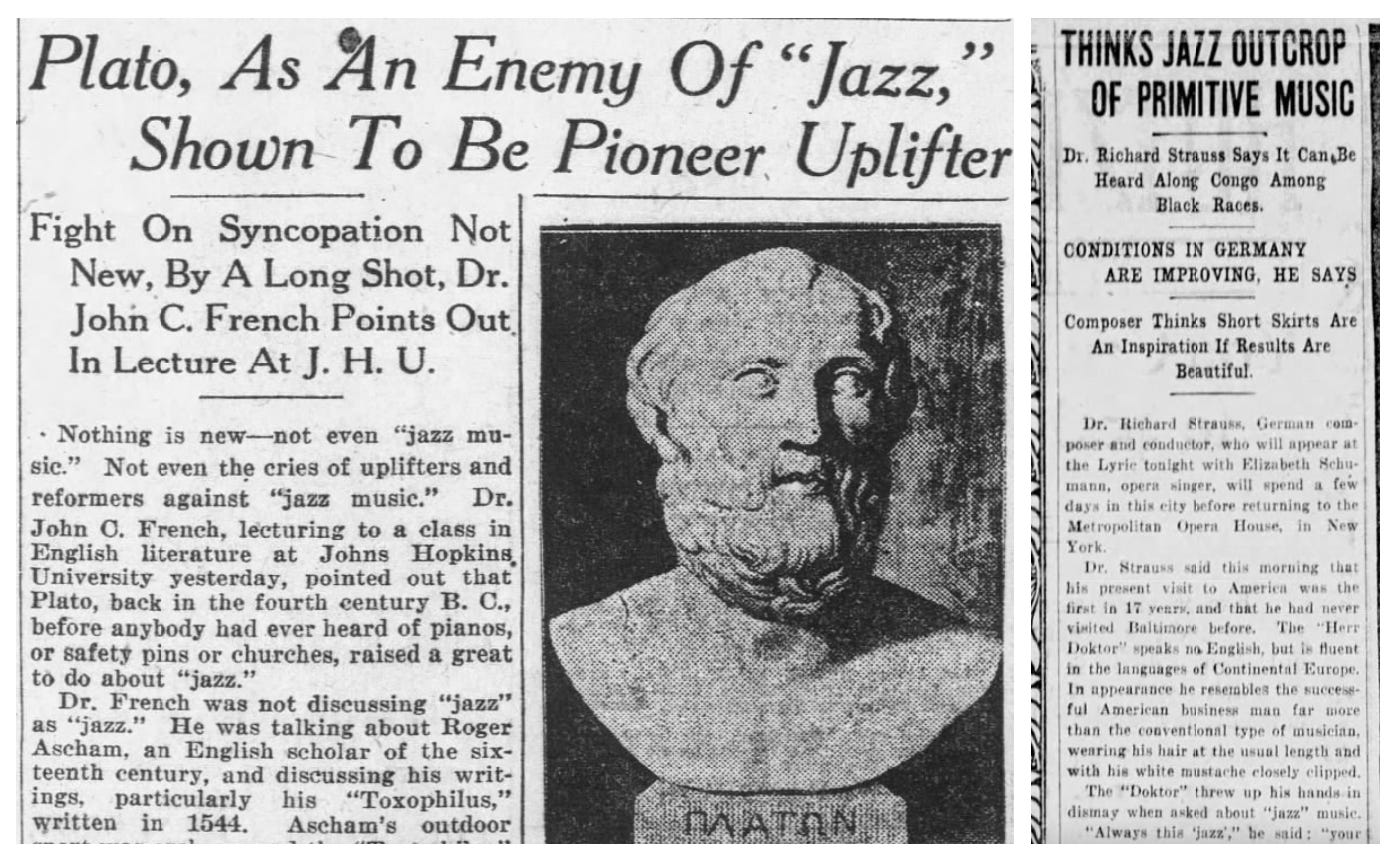

That same month (November 1921), a professor at Johns Hopkins raised the level of histrionics in Baltimore, declaring that Plato had warned against jazz thousands of years before. Decent people who opposed this harmful music were actually continuing a battle dating back to the dawn of Western culture.

By pure coincidence, composer Richard Strauss visited Baltimore that month—and was enlisted in the battle to discredit jazz music. “Your journalists always ask me about this jazz,” he grumbled, and admitted he had never heard any jazz in America—but then he obliged with a suitable putdown, based on dance bands he had encountered in Germany. “Jazz has nothing to do with music, he declared. “It is an outcrop of the old tribal music that is common to most parts of the world.”

She has attended ‘hooch and harem’ parties.

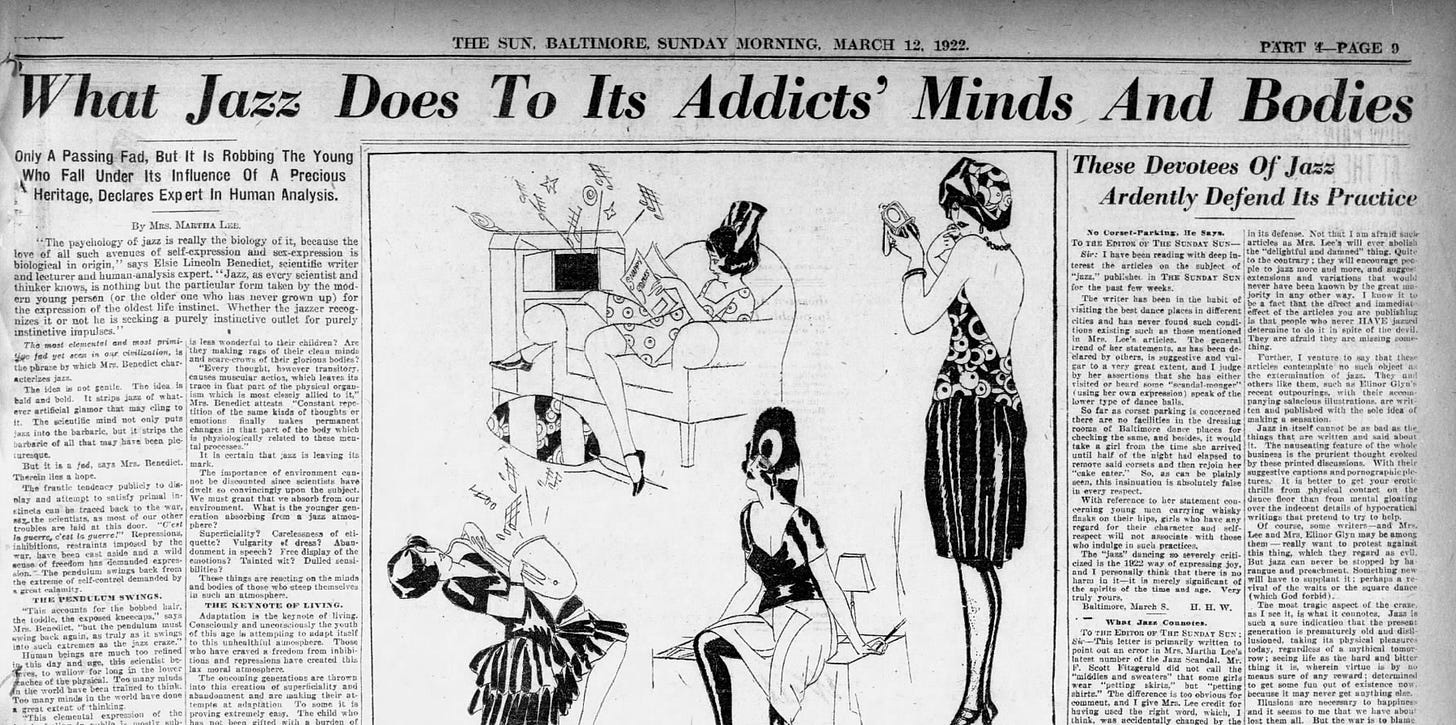

But this famous German composer was nothing compared to Mrs. Martha Lee, who started her anti-jazz campaign in the Baltimore Sun a few weeks later.

The newspaper was so excited about Martha Lee’s attack on jazz, that it announced the first installment in a huge advance advertisement. Mrs. Lee, readers were promised,

has talked to the poor and innocent victims of jazz in their own homes. She has attended ‘hooch and harem’ parties. She has heard the tales of the jazz devotees as they came out in the courtroom. Mrs. Lee knows what she is writing about.

The first installment of this ongoing assault appeared on January 22, with a banner headline asking “What Shall We Do with This Terrible Jazz?” And Mrs. Lee definitely had tawdry tales to tell, drawing on everything from crime stories to “scientists who have been experimenting in music-therapy with the insane.”

The experts she consulted agreed that:

Jazz music sends temperature up. It produces a fevered physical condition. It atrophies the fine nerve control balance. It has the same effect as alcohol…..The brain becomes so disorganized that it is actually incapable of distinguishing between right and wrong.

The comparison with alcohol is revealing. Activists like Martha Lee had made liquor illegal in the US in 1920—just two years before this article ran. This new campaign against jazz was clearly an extension of their recent success in imposing Prohibition.

If you think that a prohibition on jazz dancing was an impossible goal, just consider that 46 of the 48 states had recently voted in lockstep to ban alcohol. Both parties had supported this measure with great enthusiasm. If they could get rid of bars and booze, why not jazz and blues?

If they could get rid of bars and booze, why not jazz and blues?

One thing was sure—this anti-jazz campaign wasn’t going away.

Another attack showed up on February 12. This time, Mrs. Martha Lee promised to disclose "what insidious jazz is doing in our high schools.” And the short answer is: Everything you feared.

Over the course of this lengthy diatribe, Lee linked jazz to swearing, smoking, dirty jokes, disrespect of elders, bad manners, spooning, and a litany of other sins.

Young women who dance to jazz, eventually move on to other pursuits—where “automobiles are used as ‘apartments on wheels’.” But that was hardly necessary, because the female jazz fan, “letting the desire of the moment sway her,” soon “takes a visit to a man’s apartment or hotel room.”

These two articles rank among the longest and most intense attacks on jazz from that era (or any era). But this was only the start. Mrs. Martha Lee continued to publish new hit pieces every few days.

Just one week later, Lee explicitly stated her ultimate goal—namely that the US should pass a new Prohibition, a “national house-cleaning,” focused this time on jazz not alcohol.

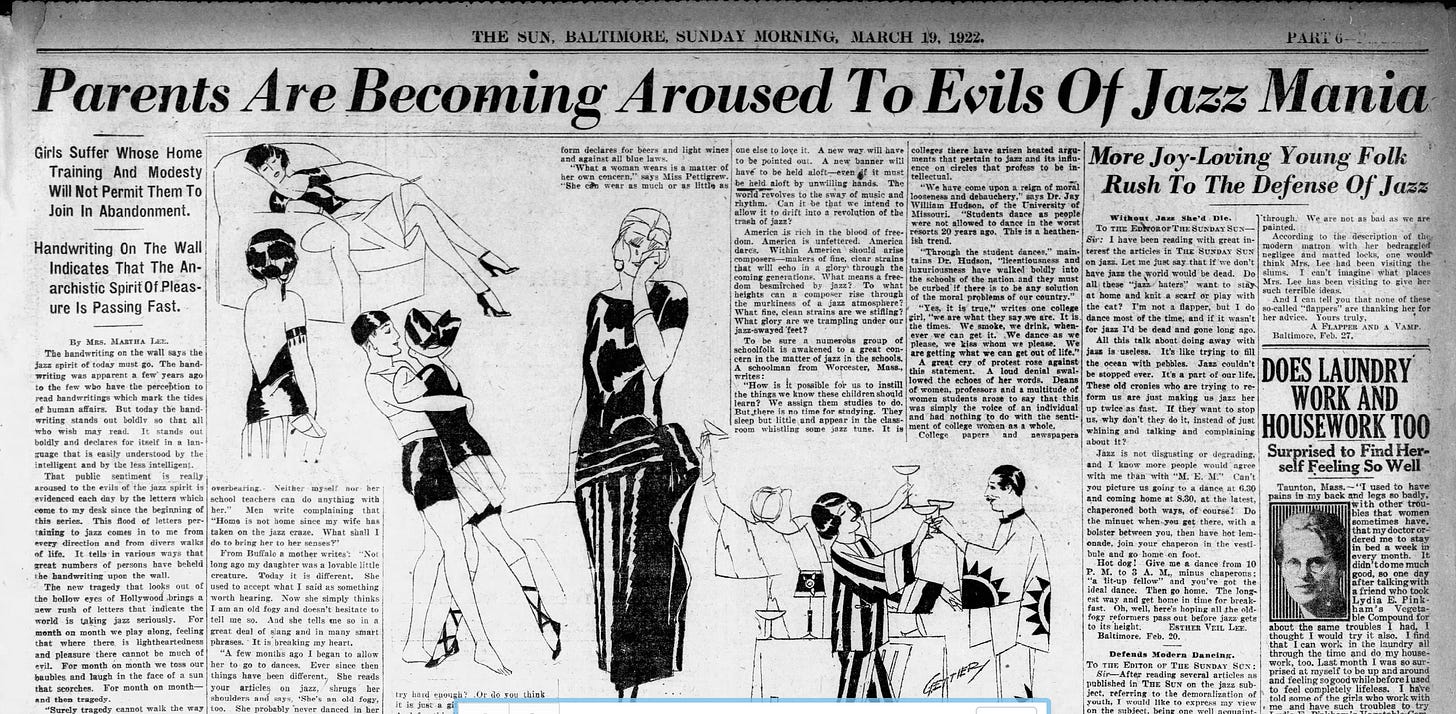

The following week, Mrs. Martha Lee revealed the scandalous impact of jazz on fashion. And (as always with Mrs. Lee) she included examples and illustrations, so everybody could gawk.

This exposé on indecent exposure—which filled an entire newspaper page—described jazz attire in no uncertain terms. These ladies were wearing “petting skirts” and “dirty dresses.” The bottom line: “The spirit of jazz is undressing our women.”

And the articles kept coming, week after week. Each one was accompanied by titillating text and illustrations.

Jazz gets you into a car accident.

Jazz makes you an addict.

Jazz ruins your marriage.

Finally, jazz forces you to get drunk and put on ridiculous pajamas.

And these are just a taste of Mrs. Martha Lee’s ongoing war on jazz in Baltimore. If you put them all together (which somebody really should do), they would fill a book.

And what happened after the Baltimore jazz war of 1922?

One last question: Who was Mrs. Martha Lee?

The curious fact is that 1923 was the greatest year yet for jazz.

Louis Armstrong made his first recordings with King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band.

Sidney Bechet recorded historic tracks "Wild Cat Blues" and "Kansas City Blues" with Clarence Williams' Blue Five.

Jelly Roll Morton made his first recordings in Chicago.

Duke Ellington performed in New York for the first time.

Bix Beiderbecke joined the Wolverines, destined to become one of the greatest Chicago jazz bands.

The Cotton Club opened in Harlem.

The Charleston took off as a dance sensation, propelled by its appealing syncopated jazz beat.

And jazz greatness was on the rise even in Mrs. Lee’s Baltimore, where future legends from Billie Holiday to Cab Calloway got their start back then.

Another milestone from 1923: Mrs. Martha Lee disappeared from the bylines of the Baltimore Sun. And, as far as I can tell, she never returned. She had gone to war against jazz—and was vanquished.

One last question: Who was Mrs. Martha Lee?

I can’t find any biographical information on her—and I have a hunch she never existed. “Martha Lee” probably was a pseudonym—much like the title character in Nathanael West’s novel Miss Lonelyhearts from a decade later. The articles in the Sun carefully avoid sharing any details about the author, and the name could hardly be more generic—especially in the South, where Lees are thicker than a bowl of grits.

But Lee, for all her intolerance of jazz, was a skilled writer. It makes no sense that she would appear in the Baltimore Sun in 1923, out of nowhere, and disappear just as completely a few months later. She was too polished and prolific during that brief spell of notoriety to be an amateur or a nobody.

In any event, the defeat of this mysterious lady set the stage for the ascendancy of the Jazz Age—which is now how historians refer to the boom times and vibrant culture of late 1920s. But that would never have happened if music and dance fans hadn’t pushed back against fierce opponents, especially an angry woman in Baltimore, who wanted to kill off the Jazz Age even before it had begun

There's no mention of race or racism here in this account, so I feel compelled to point out that how much the critiques and predictions about jazz would be repeated with rock and later hip hop decades later, and in all cases part of the backlash was inspired by racism and fears of miscegenation, not unrelated to fears of the overt sexuality that accompanies so much of popular dance cultures.

Gotta stamp out those "Jungle Rhythms" as they could stir up urges to dance & sway the Hips ... & we all know where THAT could lead !

Are we sure this Hate movement didn't originate in Florida ?