How 'American Graffiti' Invented Classic Rock (and Changed My Life)

My favorite George Lucas film turns 50 tomorrow, and I love it for the soundtrack—but for a whole lot more

My favorite George Lucas film does not take place a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away.

Instead it unfolds over the course of a few hours in the humbler setting of Modesto, California in 1962. But even modest Modesto—was the city named for its humility?—can be a universe unto itself.

There’s no Luke Skywalker or Darth Vader here, but American Graffiti does have its symbolic, iconic figures—from hot-rodding Harrison Ford to disk-spinning Wolfman Jack. And even Modesto, despite its unassuming name, has its share of tragedy and triumph—and they both unfold here over the course of just a few hours.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

The triumph is a small one—but this is a small town in inland central California, after all, not Camelot or Middle Earth. In Modesto, a town boy sets out on his personal journey, leaving his home and friends behind. He will become a writer, although we don’t see that part of the story on screen.

We only experience the painful part of the tale—leaving home behind.

I admire a lot about this film. For a start, I like how George Lucas follows the three rules of classical drama in American Graffiti. Those rigid guidelines were established by Aristotle more than two thousand years ago, and clarified by Lodovico Castelvetro in 1570.

Aristotle was a smart dude, but few movie directors have the patience to apply his rules on the screen. They feel too constraining. Yet they work like magic when handled deftly.

Here they are:

The story should transpire in a single location (in American Graffiti this is Modesto, California).

The story should occur over a period of no more than 24 hours (in the film, everything happens in the hours leading up to the protagonist’s departure to college).

The story should focus on a single overriding theme or activity (friends celebrate the last day of summer vacation).

Most movies ignore these restrictive rules. But a few try to follow them—and they include some of my favorite films.

High Noon

Glengarry Glen Ross

Rope

Twelve Angry Men

And let’s not forget Die Hard—which from this moment on should never be called a Christmas movie. It’s an Aristotelian movie.

You probably think that these three rules are arbitrary. Why 24 hours? Why one location? Who gets to decide these things?

Of all these Aristotelian films, American Graffiti is the most deceiving. It feels loose and episodic, and only in retrospect can you see how tightly controlled everything is. The three classical unities play a large part in this holistic quality, but other elements contribute (especially the music, which I’ll discuss below).

But I’d be lying if I told you that I love this film for its formal structure.

American Graffiti also has a personal meaning for me. A very deep one. At the very juncture in my life when I saw it, I felt like I was also living it.

The single biggest decision in my life was to leave my home town. It was a modest California city—perhaps not as modest as Modesto, but close.

I was happy in my home town. I had found my place in Hawthorne, California—in a tight knit web of family, friends, and social activities. And I had my own car, through a stroke of sheer luck.

Here’s the chain of events that got me wheels.

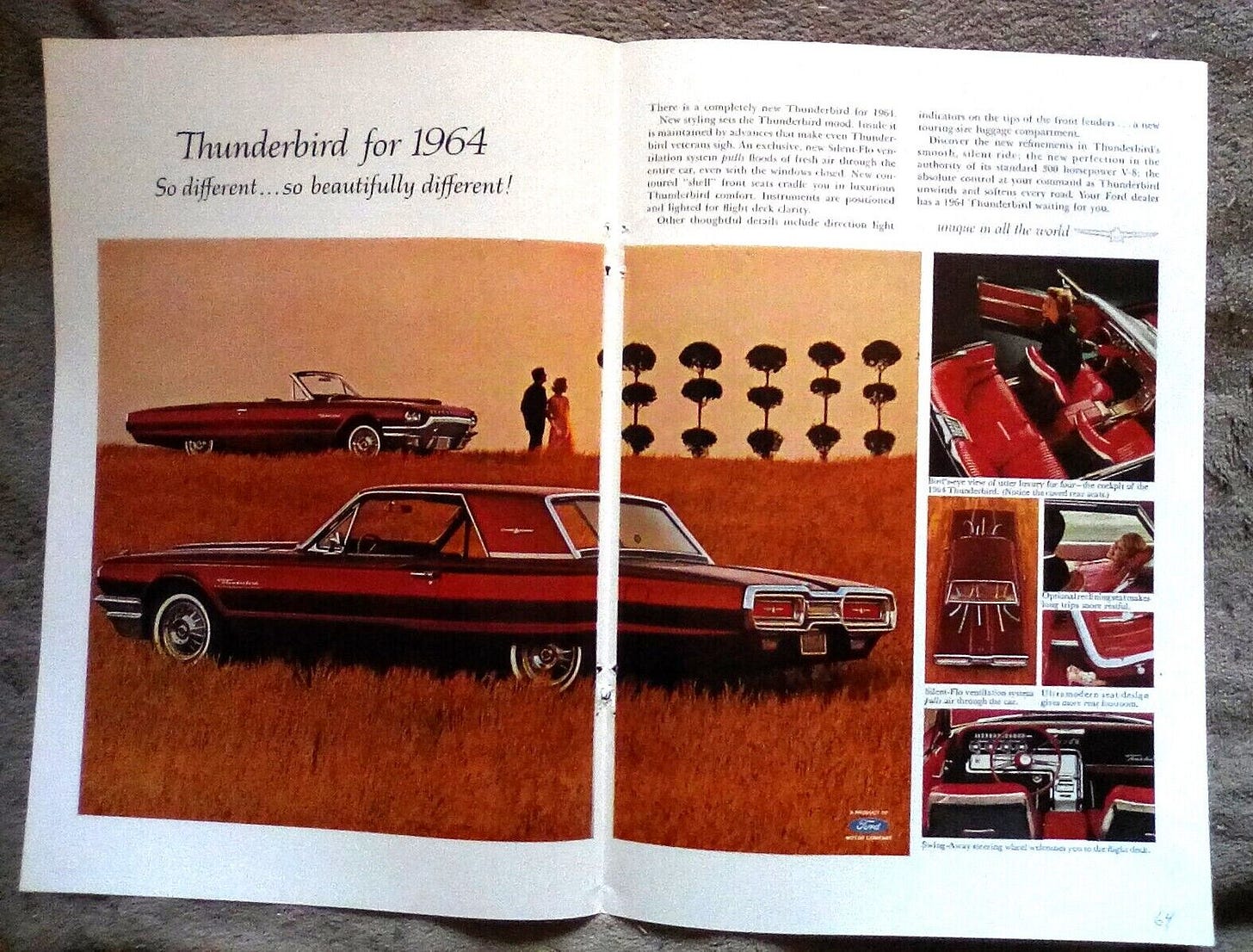

Dad bought a new auto, a boring Datsun—and gave his cool 1964 Thunderbird to my older brother Dana.

But Dana got accepted into a PhD program at Harvard, and couldn’t bring the car with him.

So at age 16, I’m given the keys to this beauty. It was a decade old by then—but this four-wheeled baby just got better with age.

I loved driving that car.

My school days had been tumultuous. Up until the age of ten, I’d had a larger taste of getting taunted and bullied than most youngsters—I was different, and that’s not always a good thing in a small town. But all that had ended by the time I entered my teens. My last couple years of high school were glorious fun.

I really didn’t want to leave Hawthorne. I would have stayed in high school forever. But it wasn’t an option.

People often talk about college as a rite of passage. But I believe the bigger transition is leaving your home town behind. You could create a whole theory of psychology and social theory based on dividing people into two groups: (1) Individuals who leave their home town at the end of their youth, and (2) those who stay.

People often talk about college as a rite of passage. But I believe the bigger transition is leaving your home town behind.

Everything changes so suddenly if you are in the first group. Sometimes things never change if you’re in the second. In retrospect, this was the decisive moment in my life—and I felt it even back then. I had to leave, but didn’t want to do it.

Not long after I saw American Graffiti, I received an acceptance letter and scholarship money from Stanford University—400 miles from my home town. The distance may not seem like much to you, but that felt like a galaxy far far away to me.

I knew I should be excited by college, an opportunity my parents had never enjoyed, and especially an elite college—this was the proverbial offer you can’t refuse. But that same elite status meant I’d soon be consorting with other students from more worldly and sophisticated backgrounds.

Here are some of the other undergraduate students at Stanford during those years: tennis legend John McEnroe, Pulitzer Prize-winning dramatist David Hwang, quarterback John Elway, neuroscientist (and author of This Is Your Brain on Music) Daniel Levitin, and Pulitzer Prize-winning composer David Lang.

Sure, they weren’t famous back then. (Okay, some of them were: McEnroe ostentatiously announced in a classroom one day: “The rest of you strive for good grades, but I strive for good tennis”—and backed it up by winning the U.S. Open a few month later.) The bottom line is that the vibe at my new home base would be elite, competitive, and intense. I thought I could handle things academically, but emotionally was a different question. It didn’t help that I was younger than most of the other students.

And I wouldn’t even have the car. My brother Dana had returned to California and as a proper rite of primogeniture took back the keys to the T-Bird.

This is the juncture when I felt like a character inside American Graffiti. And it helped me to see a movie about others who had faced with this same choice—the dilemma of staying home or going out into a challenging world. To some degree, the film gave me the courage to make the same move.

There have been ups and downs since that time, but from a larger perspective my life has been truly blessed. And it required me to leave comfort and familiarity behind and head into unknown terrain. So you can imagine my fondness for a film that helped make that happen.

Especially this particular film. Everything that happens in those 24 hours seems to hold the protagonist back. He meets a beautiful woman (who is only seen in passing, and always in a Thunderbird!—that had to be a symbolic message to me). He gets inducted into the reigning home town gang (the Pharaohs). And even receives words of wisdom from a trusted elder (Wolfman Jack).

Everything is coming up roses in Modesto for Curt Henderson. But the next day dawns, and he still gets on that plane, leaving it all behind.

In other words, this film is every bit as mythic as Star Wars—and no spaceship required.

But I also have a professional reason for celebrating this movie. That’s because American Graffiti played an important role in launching classic rock as a genre.

You may find this hard to believe, but rock radio stations all focused on new music in the 1960s. They might occasionally play an “oldie,” as they were called back then, but few people considered old rock a genre in its own right.

But around the time George Lucas was filming American Graffiti, the hottest music radio station in Los Angeles, KHJ—93 on the AM dial—was trying to figure out what to do with its FM bandwidth. For a while, it played the same current hits on AM and FM, but in late 1972 they decided to try something different—they renamed the station KRTH (101) and decided to focus entirely on rock songs from 1953 to 1963.

By pure coincidence, George Lucas was relying on these same old rock and roll songs for the soundtrack of his movie. And with amazing results—the soundtrack album was even more popular than the film, and soon broke into the Billboard top 10.

The 41 songs on the double album defined this new genre. It didn’t even have a name back then. The folks at KRTH called it the gold format. But the American Graffiti soundtrack did even better than gold—it went triple platinum.

None of this surprises you—we’ve all grown accustomed to nostalgic rock. But rock music was NOT the tiniest bit nostalgic in the 1960s. The first time I heard KRTH I was shocked. The notion that a radio station would avoid the brash and exciting new rock stars, and focus entirely on songs that were 10 or 15 years old struck me as ridiculous.

But that soon changed.

A lot of people noticed what American Graffiti had done. The next year, the Beach Boys released their Endless Summer double album—which focused entirely on the band’s old songs from 1962 to 1965. It hit number one on the Billboard album chart, and redefined the Beach Boys as a nostalgia act.

In time, many other rock bands made the same transition. A similar aesthetic vision helped launch Grease, Happy Days, and other retro offerings which redefined the musical culture of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Over time, KRTH expanded its definition of the genre, and its format name too. In 1985, they adopted the label "Classic Rock and Roll”—and now focused on songs released between 1955 and 1978.

Fast forward to today—and you hear classic rock everywhere. And a lot of it comes from that same time period. But I’m especially surprised by how many young people today know those songs, even though they weren’t alive back then.

So it isn’t nostalgia. It’s a real genre—with a surprising degree of cross-generational appeal.

And a movie helped make it happen. So American Graffiti is my Star Wars—for me, it’s just as mythic, just as timeless. That was 50 years ago. And if it doesn’t feel so long ago and far away, it’s because my life still bears the impact, and the playlist is still on heavy rotation.

The soundtrack success of "AG" was a foretaste of the Permanent Backwards Stare of the music industry; which started in earnest with "The Big Chill" in 1985. The money that soundtrack made was the foundation of the Nostalgia Industrial Complex that has blighted the prospects of two generations' worth of rock musicians ever since. My generation had to invent a whole "alternative" music industry just to have any space for our own music at all; which the bigger Industry bought up and destroyed around 1996 like Wal-Mart eating small town shoe stores throughout rural America.

Classic rock was a nice plant that should have been kept in its own pot rather than let loose in the garden to vine-strangle everything else.

Two items –

First, (perhaps apocryphal) – legend has it that the town was originally going to be named after Leland Stanford, but that Stanford demurred. So they named the town Modesto – “the modest one.” Sounds fishy, but who knows?

Second, (definitely true) - I was in high school when AG was being filmed locally. Rumor had it that if you dressed in 60s clothes you could get free admission to the gym at Tamalpais High School where Sha Na Na was playing a concert. A bunch of us discussed it, and we wiser ones scoffed and skipped it. Every time I see the dance scene I get to look at my high school buddies having fun and living forever on the big screen. Damn!