Help!—AI Is Stealing My Readers

I thought piracy was bad, but I've now seen something much worse

I’ve lost count how often my identity has been stolen.

I’ve sometimes had to take drastic steps—filing a police complaint, freezing credit reports, canceling credit cards, even contacting the FBI to warn them about an especially dangerous impersonator.

(Side note: That reprobate stopped messing with me as soon as the Feds got involved.)

In other instances, the impersonation seems harmless. Consider this bro in Vietnam who has been using my Twitter bio for the last seven years.

What’s he getting out of it—kickbacks? groupies? free tickets to V-Pop concerts?

I have no idea, but I like to imagine this middle-aged nicotine addict leading a much more exciting life than mine. He’s cruising and clubbing in Hanoi as an ex-pat American music critic. In my mind’s eye, I see him partying, carousing, and getting free drinks at the bar.

Occasionally he autographs a copy of one of my books—then steps outside to light up an imported French cigarette….

Okay, that’s my dream. And as far as I can tell, he hasn’t hurt me in the least. But who knows what goes down if I’m ever arrested in Ho Chi Minh City?

Other impersonators are less charming. Several malefactors have borrowed my name and avatar to peddle crypto on Substack. On another occasion a hacker took over my Twitter account for a few hours—pitching video game consoles and running shoes to my followers.

(I’m lucky these crooks don’t scam my audience with bogus Blue Note vinyl first pressings—that could start a real bidding war.)

You get the idea: I’ve seen all of the impersonation scams. At least I thought I had until now.

Because AI has arrived on the scene.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

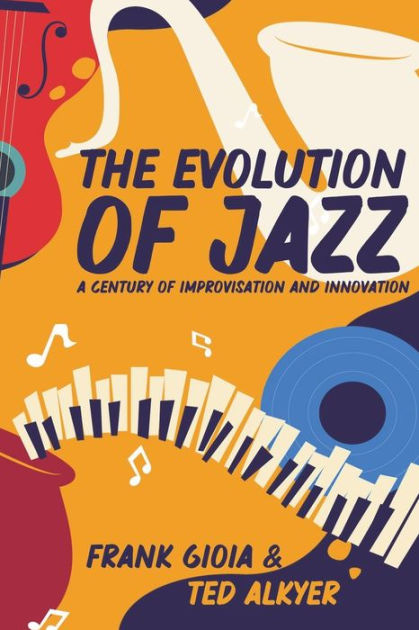

A few days ago, a friend sent me a photo of a new jazz book.

What made this especially interesting is that the author’s last name is Gioia.

What an odd coincidence. Gioia is an uncommon name. If there were another jazz writer who shared my name, I’d know about it.

The book is attributed to two authors—Frank Gioia & Ted Alkyer. As it turns out, Alkyer is also a last name familiar to jazz insiders. Frank Alkyer is editor and publisher of the leading jazz magazine Downbeat.

Another coincidence!

So I reached out to Frank, and asked him if he knew about this book. He was as shocked as me. Alkyer is also an uncommon name.

Neither of us had anything to do with this book. And we don’t know jazz writers with these names—so similar to our own.

You don’t need to be as smart as an Einstein chatbot to figure out what’s happening here. As I told Frank, I’d wager that:

The book is written by AI.

The people behind it attribute the book to two authors based on us, switching our first names so that no direct impersonation can be proven—ensuring that the book always comes up in the results when somebody does a search for either of us.

Needless to say, these two authors do not exist.

The intent is to fool readers and divert them from anything we've written to some crappy AI book.

Both Frank and I filed complaints with Amazon—and the book is no longer listed there. But it’s still available from other retailers. An audiobook has also been released.

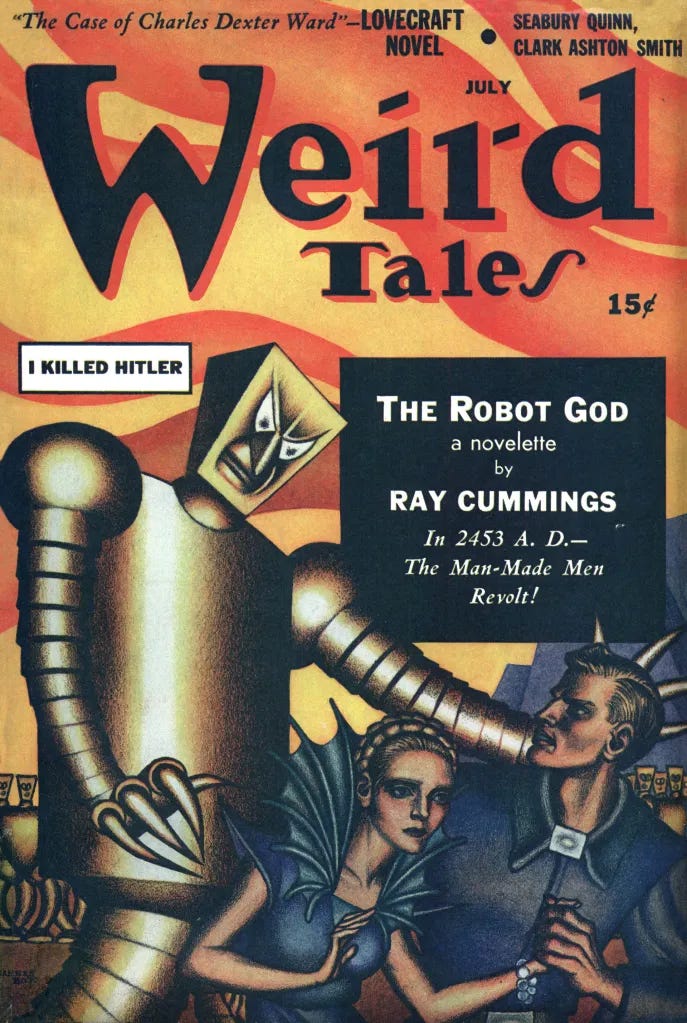

A few hours later, a Twitter connection alerted me to another interesting jazz book. It’s written by Luke Ellington.

Luke Ellington? Is he any relation to Duke Ellington?

In the aftermath, I started browsing through listings for other recent jazz books.

What should I make of another author who has released a dozen or so jazz books in the last few months?

Please savor the opening lines of three of them:

Maybe a person wrote that. Yes, there is a full bio of the author available online—but I haven’t found a photo.

There’s some heavy irony here. The AI chatbots have been trained on my books. So if a scammer uses AI to write a jazz book, it probably regurgitates things I’ve actually written myself in the past.

So I can get robbed and impersonated at the same time.

Is that fair?

It took me decades to become a jazz expert. My writing career really didn’t take off until I was in my forties—because you can’t develop mastery of this material without years of constant effort.

Does AI now get to swallow up everything I’ve learned in a few gulps—and then use it to impersonate me?

And it’s not just jazz writers getting a raw deal. Scholars and experts of all sorts are also getting exploited. In fact, the harder you have worked at your field and the more valuable your expertise, the sooner your life’s work will get digested and spat out by the AI beast.

There ought to be a law to stop this.

AI can be a valuable tool—I absolutely believe that. But scams shouldn’t be part of the process.

In the near future, I’ll dig more deeply into this troubling matter.

In the meantime I’ll close by sharing an easy solution—one I’ve repeated a lot lately.

AI advocates could end these scams by offering transparency. Just tell us when AI is used. That's a simple, fair request.

But it won’t happen unless we force the issue. The AI business model is currently based on deception. Demand collapses if they're honest.

That’s why the scamming problem will get worse—much, much worse—unless we take prudent steps. Otherwise scams will drive the economics for this powerful technology.

Is that what we want?

Coming soon: I will revisit Isaac Asimov’s “Three Laws for Robots”—and show how an updated version of them could help us fix this mess.

I’m convinced we will one day have a Certified Human stamp on creative work. The uprising is just beginning.

This is truly disturbing. Being robbed and impersonated in one fell swoop does indeed seem accurate. Everything that has troubled me about the numbers-based metrics dominating higher ed, and now publishing, finds its logical conclusion in this hellscape for artists and writers.