Here’s an amusing story, in response to Thursday’s article on the power of rhythm.

It comes from a comment by Louis Ryan, and describes an incident involving renegade Irish psychiatrist (and jazz trumpeter) Ivor Browne:

The story I want to end on was told by an ex-psychiatric nurse….She described an incident that happened while she worked in the Dublin Psychiatric Hospital, Grangegorman, where Ivor also worked.

A female patient was undergoing a particularly severe psychotic episode. The nurses were quite distressed and called for immediate medical assistance. Presently, they saw a white coat approaching. The doctor considered the situation calmly and, reaching into his coat, he drew out not a syringe but a tin whistle.

He stood there and proceeded to play a few lively jigs and reels, tapping his foot. Before long the patient ceased her rant and lined up with the nurses to examine this strange specimen of a doctor.

She looked at the others and before going calmly on her way said, “I think that fellow is a bit mad!” It was, of course, none other than the bold Ivor Browne, author of Music and Madness.

This comes from an article by Tomás Hardiman, entitled “The Mystic of Ireland: An Homage to Ivor Browne.”

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

A reader asked me for information on jazz patrons. Here’s part of my response:

I will share one story that might be of interest to you. Before Dave Brubeck became famous, he injured his back while diving in Hawaii—in fact, his neck and spinal cord injuries were so severe he almost died at the time.

After a long recuperation, Brubeck was broke—with no money to return home to California. But one day, a significant amount of money magically appeared in his bank account, and he finally could buy a ticket home.

He had no idea where the funds came from, and never found out.

Decades, later, while he was recounting this story to me (for the Smithsonian oral history I conducted in 2007) it occurred to Dave that this money might have been a gift from heiress Doris Duke. Duke's money now supports the generous cultural grants given out by the Duke Foundation, but back then she learned about Brubeck and his injury—and may have been the secret party who anonymously put cash in his bank account.

This isn't a typical example of philanthropy, but these direct interventions ought to be recognized and emulated.

Here’s the moment in our conversation when Dave (with help from his wife Iola) first realized this.

DAVE: I asked my dad, “Did you put money in my account?” He said, “No.” I asked [artist manager] Joe Glaser. Joe said no. I asked anybody….I never found out where the five hundred came from. But I’ll tell you, without saying—I just thought of something. This woman….who used to come into the club….

IOLA: Doris Duke.

TED: Doris Duke? So it might have been her?

DAVE: Yeah. She was very nice to me. I just thought of it now. Could it? Who would have money like that that I would know?

IOLA: It’s a possibility, because she came into the club, and people who came into the club were aware of the accident and what happened. So it could have been her.

TED: A miraculous story there….

IOLA: Now there’s a Doris Duke Foundation, and I hope it’s helping jazz musicians still.

DAVE: It is. It does help jazz musicians.

I play a small part in a new book.

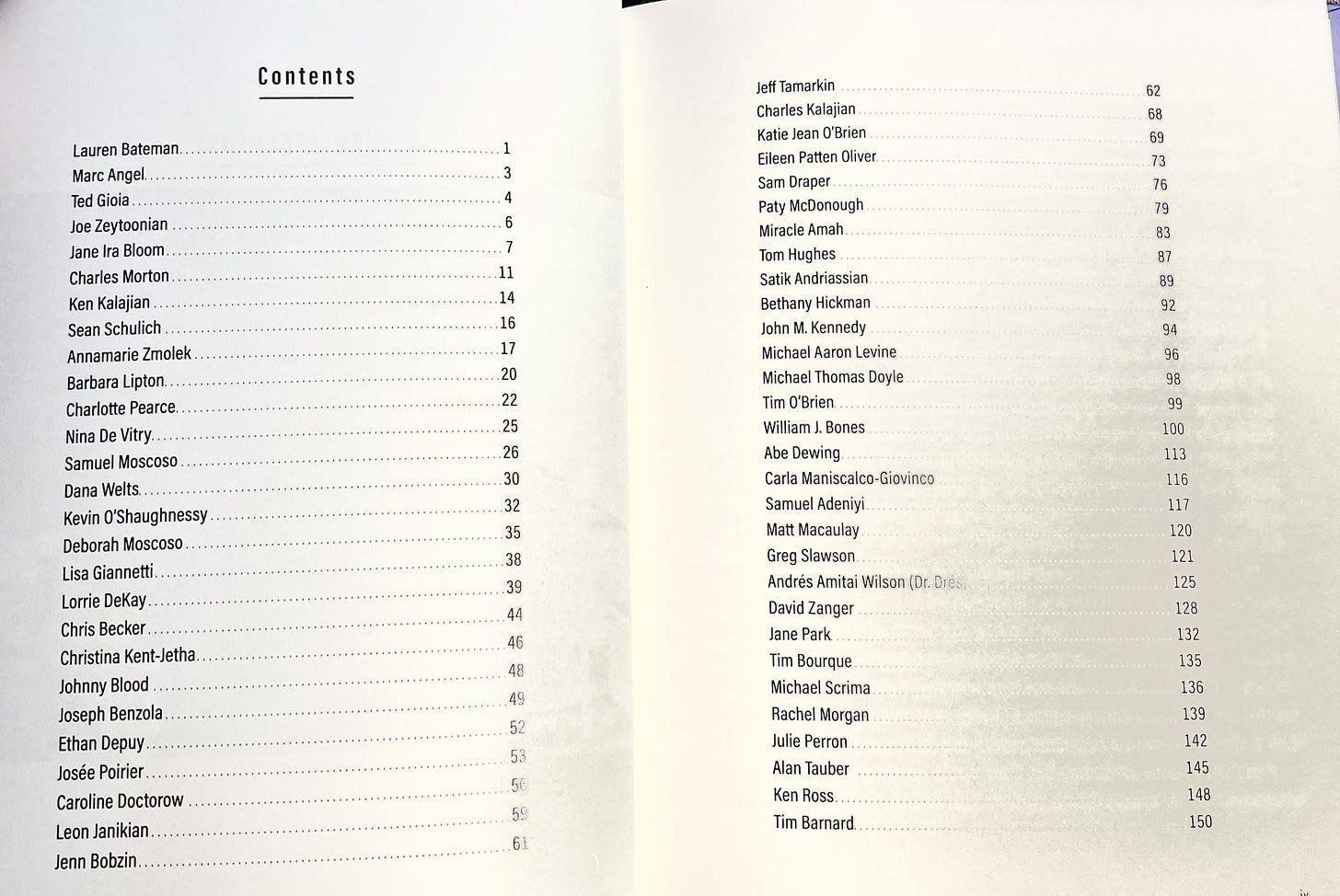

It’s called Instrumental Passion, and features aphorisms and observations on music from 57 people.

Guitarist Carolyn Zeytoonian, editor of this work, asked musicians about the role of music in their lives. The responses are as diverse as the contributors.

With Carolyn’s permission, I’m sharing with you my musical aphorisms included in the book.

You can learn more about Instrumental Passion at this link.

Ted Gioia: Aphorisms on Music

Choosing your favorite musicians is like getting to pick your own parents. In a very real way you are now one of their descendants.

Long before the Internet, music served as a kind of cloud storage used by societies to preserve their most important information. Every knowledge vocation—medicine, ministry, philosophy, law, history, etc.—was originally practiced by musicians. When we treat songs as mere entertainment, we lose not only these traditions but much of music’s inherent power.

If your music isn’t changing your life, you’ve simply picked the wrong songs.

A song is like the fish and loaves in the miracle story—everyone who hears it can keep it, and it’s still there for the next person.

What a great gift music is: It gives us satisfaction even before we’re born, soothing us as we listen to the rhythm of our mother’s heartbeat, and it’s one of the few joys we can still experience in our final days.

Philosophers treat music as a kind of aesthetic experience, but it’s more a physiological force. Long before a song impacts our ideas, it has already changed our bodies.

If I only get to bring one recording to a desert island, the lyrics better be about how to make a boat.

I had hernia surgery when I was 25 years old. I couldn’t play the saxophone for about three weeks. But I would play the penny whistle every day instead. It is a free blowing instrument, so there is no pressure from the diaphragm. So that is my pennywhistle healing story.

Brilliant, as always Mr Gioia! I so enjoy your perspective. Thank you!