Hamlet Is the Gen Z Story We Need Right Now

It’s a familiar story these days. You might even be living inside it. Or, if not, you know somebody who is.

A young man returns from college, but he doesn’t have a job. So he moves back home. But here his life is aimless, and he falls into a deep depression.

Even though he is back home, it doesn’t feel that way. He’s disconnected from friends, and his loneliness grows more intense. His relationship with his girlfriend falls apart. He knows he needs to get his act together—but how?

It’s not all his fault. His family is a mess, and he lives in a broken household. His mother is a head case. His absent father is too demanding.

And the whole social and political situation is fractured. Our sad young man feels like one more victim of the pervasive dysfunction.

It’s the classic Gen Z dilemma. Almost half of them move back home after college nowadays. The odds are stacked against them at every turn.

But the story I’ve just told isn’t about Gen Z. It’s Shakespeare’s Hamlet—and it was written more than 400 years ago.

Please support my work—by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

It’s almost uncanny how relevant it feels right now.

So if I were directing Hamlet in the current moment, I’d give the title character an iPhone and game console. I’d have the characters onstage share photos on Instagram—and put up a big screen so the audience could see them posted in real time.

Hamlet could add pithy captions to his social media images. What a piece of work is a man! or maybe The lady doth protest too much!

Yes, Hamlet is many things, but one of them is, perhaps, a failed influencer.

Along the way, we may have answered the classic question about this play. For generations, critics have wondered why Hamlet wastes so much time, and can’t be bothered to take action.

Maybe he’s just too busy gaming and scrolling.

Okay, it sounds ridiculous. But is it really? Shakespeare possessed tremendous insight into the human condition—perhaps more than any author in history. So maybe he really did grasp the dominant personality types of our own time.

The Prince of Denmark still walks in our midst. And maybe—just maybe—careful attention to this play might help us, in some small degree, to heal the Hamlets all around us. Their number is legion.

Of course, the larger reality is that Shakespeare has proven himself relevant to every time and place. We can see that easily be examining how other generations viewed this same play.

Hamlet’s original audience, four hundred years ago, clearly enjoyed the spectacle of violence and adultery. Nine key characters die during the course of the play—most of them murdered. Audiences loved these kinds of dramas back then, and Shakespeare always knew how to please the crowd.

But more sophisticated viewers, circa 1600, would have seen Hamlet as a political commentary—a reflection of all the tensions and rivalries of Elizabethan England. Nobody knew better than Shakespeare that monarchy is a dangerous game, and he always looked for opportunities to refer to current events in roundabout ways.

But two hundred years later, the Romanticists were in ascendancy, and they saw Hamlet as a very different kind of play. They ditched the politics, and embraced the Prince of Denmark for his pathos and personality. They tapped into the intense emotional currents of Shakespeare’s heroes—and the plays seemed perfectly suited for this kind of interpretation.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Hamlet continued to change for each new generation. He always feels timely and relevant.

A hundred years ago, critics began grappling with psychology and the unconscious—and Hamlet was a perfect character for these kinds of interests. In his 1900 book The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud focused on Hamlet as a case study in repression.

And who could disagree?

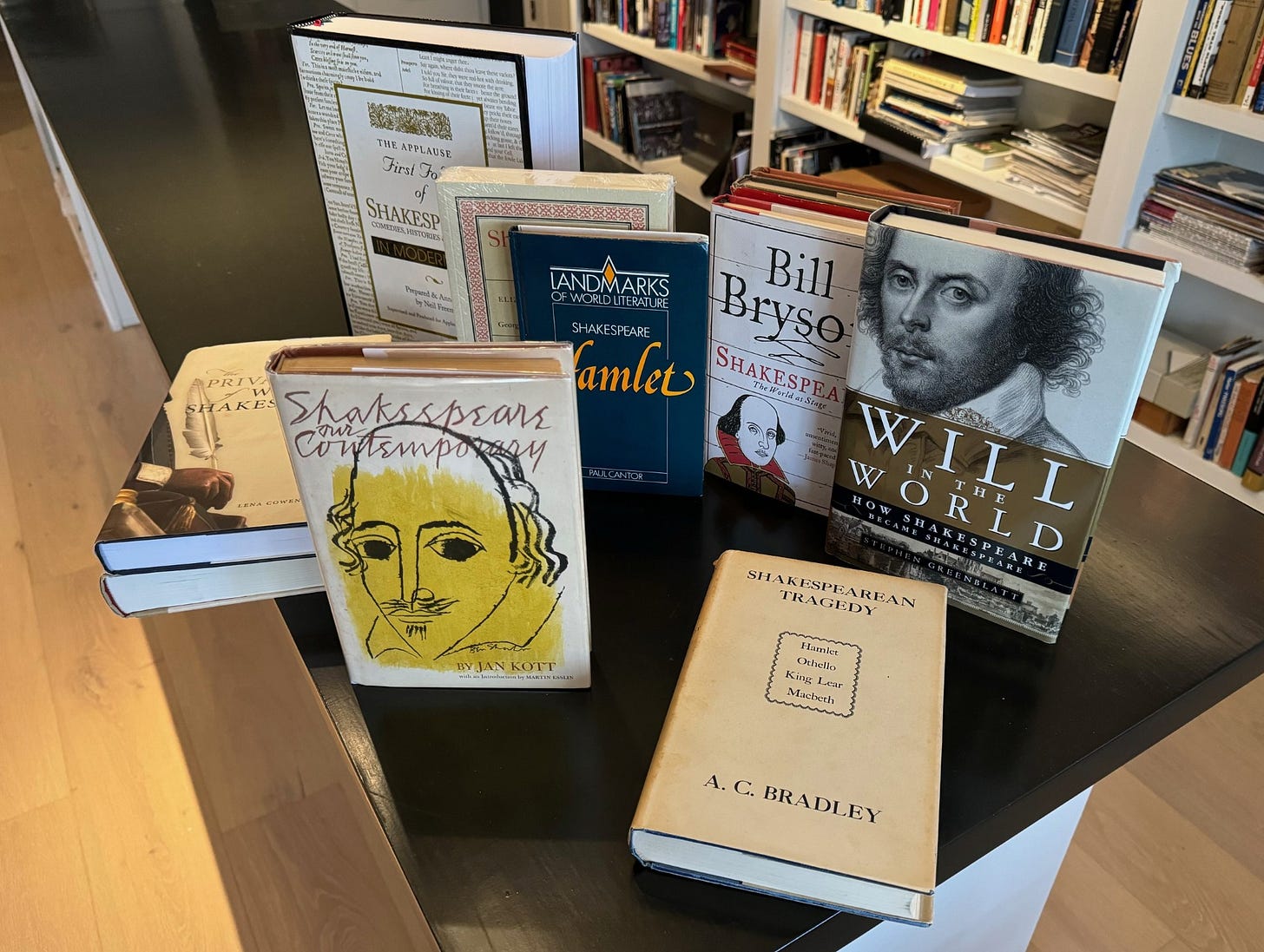

But fifty years later, Hamlet changed again. It now was the perfect play for those who had survived World War II. Jan Kott insists, in his book Shakespeare, Our Contemporary, that these old plays were more relevant than ever during the Cold War—just as timely as Beckett or Sartre or Brecht or Ionesco.

If you were an existentialist or absurdist or beatnik, you recognized Hamlet as one of your own. He was lost in a meaningless world—but so were the other survivors of World War and economic collapse and the Holocaust. So were all the other sad young men, caught in a losing war against conformists.

And now today we recognize a completely different Hamlet:

He’s the college graduate who can’t pay off all those student loans.

He’s the over-educated and under-employed worker who can’t get a job because of AI.

He’s the incel who can’t forge a relationship.

He’s the unhappy child of a broken home, struggling with depression.

He’s the scroll-and-swipe phone addict who retreats from the world, but at a devastating psychological cost.

He’s the person posting cries for help on social media—but nobody listens.

Go read Hamlet’s soliloquy again—that anguished “To be or not be….” filled with what we call (nowadays) suicidal ideation—and it fits all these gloomily familiar personality types.

Maybe that’s why pop culture is rediscovering Hamlet right now. Taylor Swift’s new album even leads off with a Hamlet track—“The Fate of Ophelia.” She must have encountered these same personality profiles, and fears the consequences.

The New York Times even suggested, in a recent opinion piece, that Hamlet might be a great story for children. There’s even Hamlet breakdancing, if you know where to look.

And dare I say that Hamlet might be the perfect inspiration for a video game?

But Shakespeare is wise—maybe even wiser than pop culture. And he constantly reminds us that Hamlet did not create his dysfunctional world. He’s a victim, too (literally so at the end of the play), and deserves our sympathy.

The same is true for all the Hamlets in our society today—even the ones in your neighborhood, or maybe your home. They need our compassion even more than our stern judgment. They are blamed for the chaos but much of it is the result of what previous generations have left them.

One of the many lessons of Shakespeare’s play is that there’s a heavy price to pay—in violence and social destruction—if we don’t help them out. When Hamlet fails, we fail along with him.

That’s why many of the familiar interpretations of this play miss the key point. Critics love to focus on Hamlet’s indecision—but he also deserves better options. And a society that doesn’t offer them is more culpable than the sad young man on stage.

He doesn’t create his tragedy. It’s set in place even before Act One—and the same is true for us today.

Yes, I fear that we are now living in our own rotten state of Denmark. But I also know that many of you already understand this, and want to push back against the pervasive dysfunction. There are millions of us now, and our ranks our growing.

This should give us some confidence, and a renewed sense of purpose.

Those are the two things that might have saved Hamlet—confidence and purpose. But they need nurturing and support from outside. That’s our responsibility.

By the way, I also hear from the young Hamlets themselves. They reach out to me, and many have a very acute grasp of what they’re dealing with—and want to find a way out.

They don’t want to be victims. And I don’t blame them.

No, we can’t rewrite Shakespeare’s play. We can’t bring those dead characters back to life, or fix a Danish succession crisis. But we can read Hamlet and learn from it. Maybe that’s Shakespeare’s gift to us.

And then there is this:

https://science.psu.edu/news/astrophysicist-finds-new-scientific-meaning-hamlet

Which is weird since I just saw a great video of Judi Dench, Shakespearean actress extradordinaire, discovering by Ancestry her Danish ancestors were the noble Bille family, who happened to be married to Tycho Brahe family, and he being a brilliant Renaissance astronomer with relatives called Rosenkrans and Guildenstern, and somehow they postulate that Shakespeare may have done a royal Danish command performance before all this . . .

As they say, you just cannot make this stuff up.

P.S. The Judi Dench book, Shakespeare, the Man Who Pays the Rent, is brilliant and historical Shakespeare insight.

There's a special providence in

the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, 'tis not to come; if it be

not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come: THE READINESS IS ALL.