Getting to the End of Gravity's Rainbow

Thomas Pynchon didn't make it easy, but that was half of the allure of his big book

They say that nobody gets to the end of the rainbow. But just wait until they try to reach the end of Gravity’s Rainbow. Now that is a real journey.

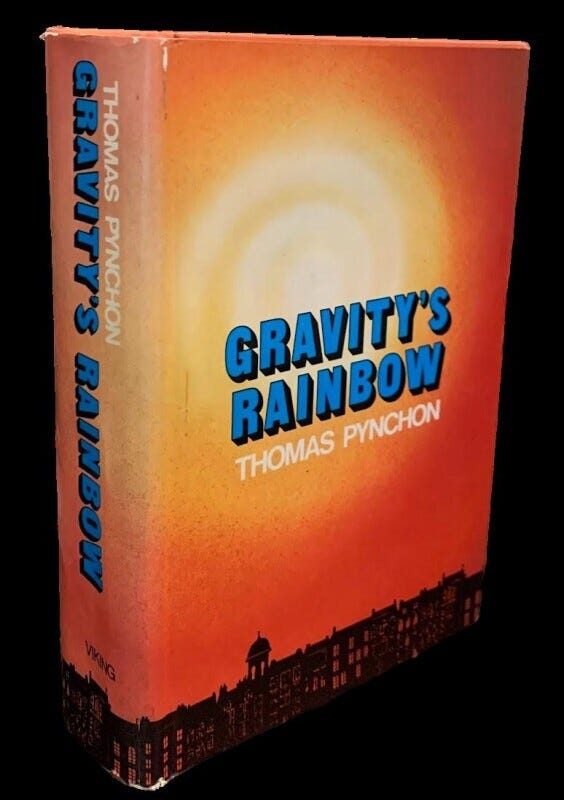

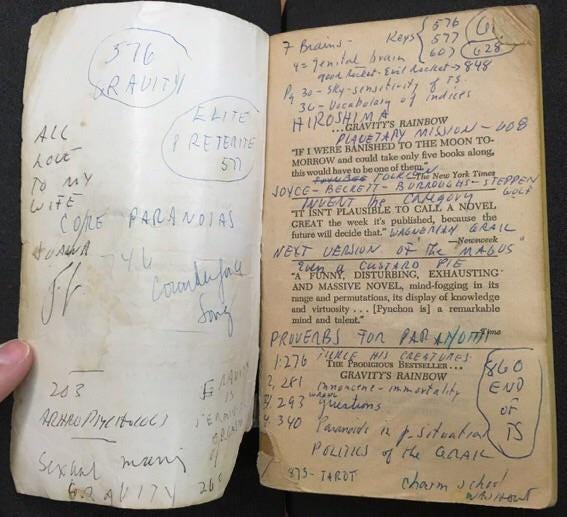

Only twice in my life have I a relied on a guidebook to help me make it through a novel. I would have certainly met my doom somewhere between Scylla and Charybdis if, in pursuit of James Joyce’s Ulysses, I had not kept Don Gifford and Robert Seidman’s 700 pages of annotations at my side. My other literary survival manual came into play when reading Thomas Pynchon's Gravity’s Rainbow—here my lifeline was Steve Weisenburger’s guide to the sources and contexts of this 300,000 word behemoth.

The fascination of what’s difficult Has dried the sap out of my veins…

Thus wrote Yeats. But the Irish bard didn’t live long enough to experience Gravity’s Rainbow, having exited the stage around the time Mr. Pynchon showed up on the scene. Yet that whole period, from late Yeats through early Pynchon, might be considered, in retrospect, as the Age of Difficulty, the time when readers expected a certain degree of hardship when addressing new literary masterworks.

But Gravity’s Rainbow wasn't just hardship, it was a bloody gulag. Once you entered, there were no guarantees you would ever emerge. Countless souls never survived it to the last page, without even a Solzhenitsyn around to document their struggles and failures.

Even from the start, the verdicts were mixed. When a three-member Pulitzer Prize jury recommended that Pynchon’s novel receive the award for fiction, the Pulitzer board over-ruled them—as a result, no fiction award was given out that year. In a strange twist—one that might have surprised even the reclusive author—Gravity’s Rainbow was nominated for the Nebula, a prestigious science fiction award, but lost out to Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama. When Pynchon’s weighty novel did rack up a big honor, the National Book Award, the author didn’t bother to show up for the ceremony, sending comedian Irwin Corey—famous for his impersonations of a drunk professor—on his behalf.

Ralph Ellison introduced the faux Pynchon. And then this ensued.

Is Gravity’s Rainbow really a work of speculative or science fiction? Certainly science and technology play a key role in this novel, where they are mixed with fantastic and paranormal elements. We are given hints about a puzzling missile component from World War II, a black box constructed out of a mysterious plastic called Imipolex G. We are presented with a quasi-mystical correlation between the love life of character Tyrone Slothrop and the location of V2 missile bombings. We encounter many elements of the occult and metaphysical, with Tarot-related symbols playing an especially noticeable role. An ambitious critic might even construct a mathematical interpretation of Pynchon's work, celebrating its persistence in turning probability and statistics on their head—although I suspect that for our author this twist is more an application of Jung’s concept of synchronicity than the playing out of a sci-fi worldview.

"Pynchon creates a world in which some subatomic characteristics of reality are dealt with at the level of everyday life," Professor Kathryn Hume has written, in defense of the sci-fi credentials of Gravity’s Rainbow. "Pseudo-Heisenbergian uncertainty bedevils the main characters, but even more important it constrains the readers." Professor David Ketterer has countered with a diametrically opposed position: "I can testify that [Gravity’s Rainbow] is not a work of SF in any real sense," he writes. "Furthermore in my opinion it is not a particularly good book marred as it is by a kind of elephantiasis…."

So whom do we back in this game of dueling professors? I have no problem acknowledging the sci-fi elements in this book. But, in all fairness, almost everything shows up at some point in this immense novel. I remember hearing locals describe a specific Paris café where, if you waited long enough, anybody you wanted to see would stroll by the sidewalk tables. Gravity’s Rainbow is the literary equivalent. If you keep pushing ahead you will find every possible ingredient—philosophy, poetry, silly songs, puns, equations, pop culture references of various sorts, real and distorted historical events, and the interaction of some 400 characters.

Perhaps the most surprising ingredient of all arrives in part three of this labyrinthine work. During the course of the section entitled "In the Zone," Pynchon actually delivers a taut, straight narrative without any of the campy or over-the-top qualities that permeate the rest of this novel. In this interlude, German rocket scientist Franz Pökler is allowed to enjoy annual visits with his daughter Ilse—although he harbors a deep suspicion that the woman he is allowed to meet is not really his child. This compelling sub-plot, rich in psychological implications, stands out as the most perfectly realized section of a turbulent novel. But for Pynchon, the switch to a quasi- Dostoevskian realism is just the exception that proves the rule, the clinching demonstration that no narrative style is excluded from this author’s playbook.

In the final analysis, this very all-inclusiveness stands out as the most salient characteristic of Pynchon’s novel. The postmodern impulse to allow all styles, all contents to mix and mingle, to rub shoulders no matter how foreign their origins, finds its most complete realization in this big book, which respect no boundaries, knows no limits. Such a project is ultimately bound to produce vertigo among its readers, and disappoint those who are seeking some unifying vision, some holistic stance behind it all.

Yet Gravity’s Rainbow always seems to hint that this grand blueprint is just around the corner. This is part and parcel of Pynchon's most characteristic attitude, namely his paranoia. The paranoid always believe that some huge conspiracy theory exists that can connect all the dots, resolve all the mysteries, settle all the bets. In a book in which paranoia looms so large, readers are bound to expect the same thing. Gravity’s Rainbow is premised on an ultimate explanation that, in the final analysis, it cannot deliver.

In retrospect, Gravity’s Rainbow must be seen as an end-of-an-era work—an ironic verdict given how its most fervent fans embraced it, at the time of its initial release, as a pathway to the literary future. But such disappointed expectations were part and parcel of many things that arrived on our doorstep around the time the promises of the 1960s gave way to the realities of the 1970s. After Gravity's Rainbow, the rules of literary fiction changed again, mostly in ways Pynchon could not have anticipated. Different styles came into ascendancy—minimalism, magical realism, postcolonial fiction, genre mashups of various sorts, trailer park verism—in the years following its publication. In more recent decades, an even more surprising twist, namely the avoidance of almost any sort of ideology (you can call this the Franzen syndrome, if you like), has begun to permeate the world of literary fiction, as more and more novelists focus on plot, character development, pacing and plain old fashioned storytelling.

In such an environment, Pynchon may still have many admirers, but few who are willing to follow in his footsteps. Even an explicitly Pynchonian novel of more modern times, David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, eventually rests its fictive universe on a compassionate, humanistic foundation, one that has no equivalent in Pynchon’s worldview. If Pynchon’s books were boats, they would be ones without a sea floor on which to set anchor.

Even if daring young writers today were bold enough to adopt Pynchon as a role model, their publishers would almost certainly refuse to go along for the ride. Just as Pynchon’s refusal to give interviews and make appearances would not be tolerated in a novelist making a debut today, the kind of large rambling books he built his reputation on would be DOA when they showed up on an editor’s desk.

For these very reasons, Gravity's Rainbow is likely to seem just as prickly and uncooperative fifty years from now as it did when it was first published. Perhaps even more so, as readers forget what it is like to grapple with deliberately difficult works. Yet I suspect that this is exactly the kind of equivocal legacy Mr. Pynchon would want for this daunting, bloated book.