Don Quixote Tells Us How the Star Wars Franchise Ends

We can predict what will happen to Disney brand franchises by studying how past pop culture narratives collapsed

Lately, I’ve been wondering how Star Wars ends.

Let me be clear, I’m not worried about how the story resolves, or what happens to the characters. I have zero interest in all that. Darth Vader can win the Nobel Peace Prize, for all I care.

I’m more concerned with how a powerful brand franchise loses its stranglehold on the culture. And it’s not just Star Wars, it’s all those other stories that never achieve closure. I’m talking about Batman and Indiana Jones and James Bond and the Marvel Cinematic Universe (or MCU, for short), and the rest of them.

They all die, sooner or later. But how?

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Heroes in capes and colorful costumes seem invincible now, if only because these fictional flâneurs are bigger than anything else in commercial culture. If Spiderman and Batman were real people, they would boast higher incomes and net worth than any flesh-and-blood entertainer in the world. The Marvel Cinematic Universe, which Disney acquired back in 2009, must be worth ten or twenty times the $4 billion they spent back then—total revenues from Marvel brands since then are somewhere around the one trillion dollar mark.

No pop star in history has ever possessed that kind of earning power.

Can these franchises just go on forever? The management team at Disney certainly must hope so, judging by their never-ending slate of Star Wars, Marvel, and other brand extension offerings. No Time to Die isn’t just the name of the 25th James Bond movie, but a promise for the future—why not another 25 films in the series? Or 50 or 100?

But brand franchises do die, or become so tired that few people care anymore. Universal Studios made so much money from Ma and Pa Kettle films that these corny comedies allegedly saved it from bankruptcy in the 1940s, but by 1960 audiences had lost interest in the predictable formulas of the series.

The Carry On films were the most dependable audience draw in British comedy, but after 31 movies the franchise could carry on no longer. A final resuscitation attempt after 14 years not only failed at the box office but was voted the worst British film ever made.

Some franchises not only die, but become genuinely toxic as attitudes evolve—killing, for example, the Charlie Chan franchise, and making it unlikely that Tarzan or the Lone Ranger or many other once lucrative brands will ever enjoy another meaningful payday.

None of this should surprise us, because narratives and protagonists go in and out of fashion like anything else. A story that charmed your grandparents is unlikely to interest your grandchildren.

As a case study, I want to examine the death of the most popular story in the history of stories, and show you how it died from over-exposure and too many brand extensions. This is an interesting case study in its own right, but also may help us understand how Star Wars, Marvel, and other dominant franchises of our own time may prove to be less invincible than their superhero protagonists.

I’m referring to the obsession with knights and their adventures—and especially those linked to King Arthur and his Round Table. These were the most popular stories in Europe for hundreds of years. Readers couldn’t get enough of them, and even as the stories got stale and predictable, the audience demanded more and more.

The situation is almost exactly the same as the Marvel Cinematic Universe. We have a major character named King Arthur, but he was linked to numerous spinoffs and sequels. The other heroes connected to him soon established their own brands—including Lancelot, Merlin, Gawain, Tristan, Percival, and many others. Readers who enjoyed one of the heroes, often became fans of others.

If you make a list, the Arthurian Narrative Universe (ANU) has more than fifty protagonists. Not all of them became major brands, but that’s no different from the movie business, where even Disney can’t keep every superhero on the payroll.

Even more to the point, these stories were business initiatives, expected to enrich their owners. It’s hardly a coincidence that the most influential collection of stories about King Arthur in English, Le Morte d'Arthur published in 1485, originated as a profit-making venture by the earliest commercial publisher in Britain.

William Caxton was not only the first person to set up a printing press in England, but also the first retailer of printed books in the country. He acquired the manuscript of Le Morte d’Arthur from Thomas Malory, the Stan Lee of his day, and turned it into the single most influential secular British book between the time of Chaucer and the rise of Shakespeare.

He didn’t do it because he loved English history. (The painful truth is that very little—in fact next to nothing—in the Arthurian tales comes from documented historical events.) He didn’t even publish the book because he loved a good story. Caxton wanted to make a buck—or a pound sterling, I ought to say. He had identified the right brand franchise, much like the Walt Disney Company in the current day, and would milk it for all it was worth.

But here’s the most amazing thing about his brand franchise: Arthurian stories had been circulating in manuscript for more than 300 years at this point. And many of the details in these narratives are much older than that, reaching back to accounts of knights who fought in the Crusades, if not earlier.

We can trace the story of Lancelot and his adulterous romance with Queen Guinevere at least back to 1180. The story of the knights’ quest for the Holy Grail dates at least back to 1190. The first mention of King Arthur is no later than 828 AD.

Stop and consider the implications. King Arthur was the most popular brand franchise in secular narratives when he was 650 years old!

Of course, it was absurd. Nobody undertook knightly adventures of this sort during the Renaissance, but storytellers pretended otherwise. Everything about these narratives was outdated, unrealistic, and repetitive—the people who read these tales didn’t own suits of armor or compete in jousting tournaments. Those things had disappeared from society. But the audience still wanted these stories, so the same plots and characters got recycled again and again.

But then it stopped. Maybe not completely, but the brand lost is power. People decided they wanted a different kind of story—more realistic, more psychologically nuanced, more aligned with their own lives and times.

That new style of storytelling was called the novel.

When the novel began gaining popularity, those old stories about King Arthur started to look stale by comparison. Even worse, serious readers treated those knightly adventures as little more than a joke—maybe something to amuse youngsters, but not worthy of comparison to the sophisticated, multifaceted novels that were now showing up everywhere.

This is an important shift in the history of storytelling, and we need to pay close attention to it—because this is how Star Wars ends. This is how the Marvel Cinematic Universe loses its mojo. This is how the movie business will eventually reinvent itself.

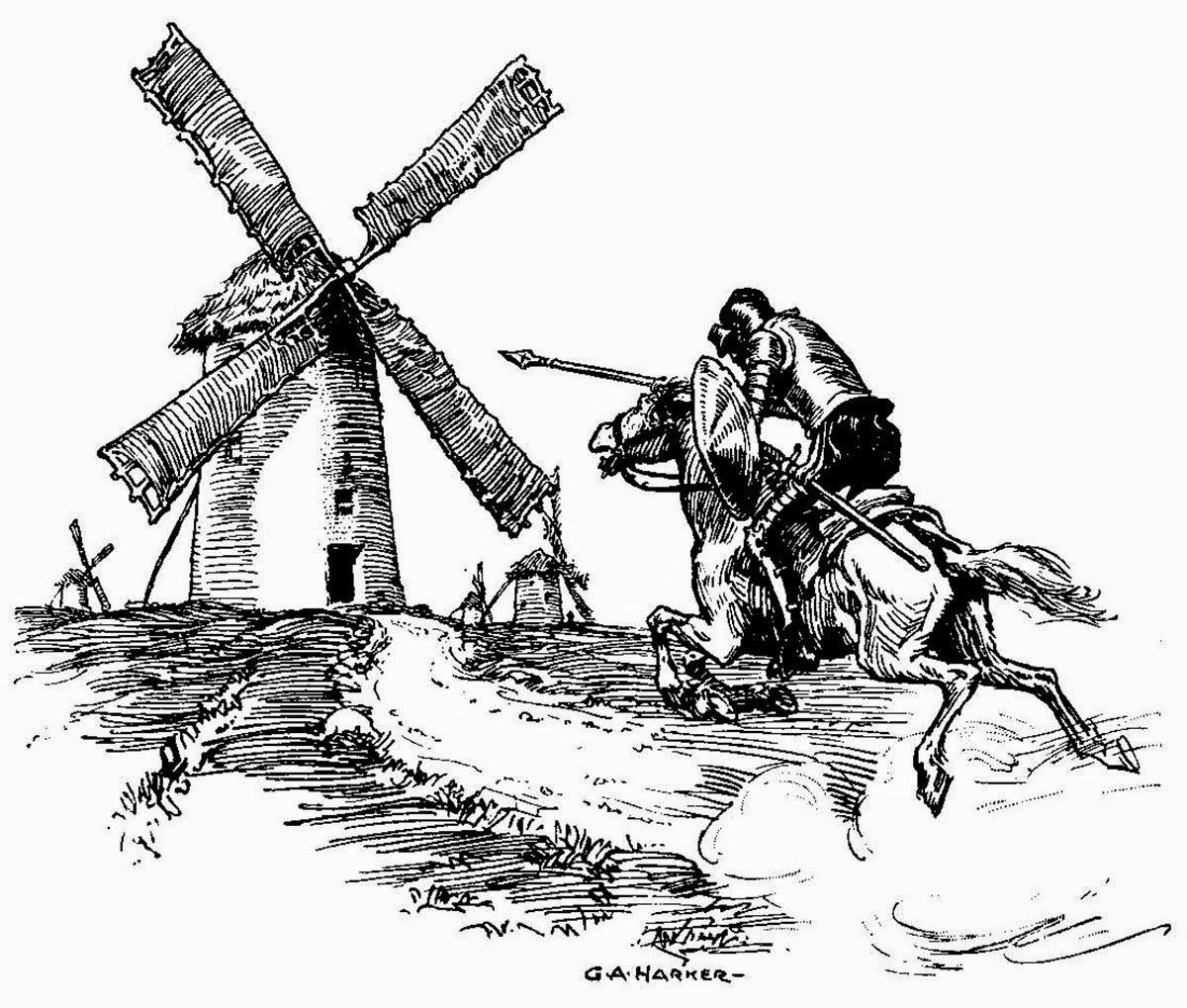

The key person here is Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616). And the amazing thing is that he relied on a knight to kill all the other knights, and clear the way for the rise of the novel.

Cervantes’s knight was the famous Don Quixote, celebrated in the book of the same name. And we could argue endlessly whether this book was, in fact, the first novel. The exact chronology here isn’t the key issue. The more pressing point is that Don Quixote made all the earlier books about knights look ridiculous. In other words, Cervantes pursued the literary equivalent of a scorched earth policy.

The title character in his book is a shrunken and shriveled man of about 50, who has gone crazy by reading too many stories about knights and their adventures. In a fit of delusion, he decides to leave home and pursue knightly adventures himself—but the world has changed since the time of King Arthur, and our poor knight errant now looks like a fool. Other characters mock him, and play practical jokes at his expense—and simply because he believes all those lies in the brand franchise stories.

We start to feel sorry for Don Quixote, even begin cheering for our hapless hero. Thus this protagonist, in Cervantes’s rendering, is both absurd and endearing. This is what raises the novel above mere satire—because we eventually come to admire Don Quixote for holding on to his ideals in the face of a world where they don’t fit or belong.

In other words, there is much to praise in this book, but this three-layered approach to reality is perhaps the most interesting aspect of them all. Here are the three layers:

Don Quixote is just an ordinary man, not a hero by any means.

But in his delusion, he pretends to be a hero, following rules and procedures that are antiquated and irrelevant. They merely serve to make him look pitiful and absurd.

Yet by persisting in this fantasy, he actually does turn into a hero, although a more complex kind that anticipates the rise of the novel. He is the prototype of the dreamer and idealist who chases goals in the face of all obstacles.

The end result was that the old fake stories of knights were now obsolete, but something smarter and more sophisticated emerged in their wake. After Cervantes, readers demanded better stories—and not just the intellectuals and elites. The novel soon became the preferred narrative format at all levels of literate European society.

Believe it or not, this could happen again, even in Hollywood.

I can’t give Cervantes total credit for this cultural shift. For example, Shakespeare created a comic knight character around this same time—Sir John Falstaff, who proved so popular he appeared in three separate plays. But, as with Don Quixote, Falstaff falls far short of the knightly ideals of the past. Yet this is what audiences, circa the year 1600, now wanted. They preferred to laugh at a failed knight rather than admire a successful one.

The cumulative impact was devastating for the Arthurian brand franchise. It never completely disappeared, but that hardly mattered. The larger truth was that the audience moved on, and would never embrace knightly adventures with the obsessive enthusiasm of previous generations. A brand franchise that had dominated popular culture for centuries had finally grown old and irrelevant.

Will the brand franchises of today end in the same way?

It’s not only possible, but inevitable. The companies promoting them are so greedy that they keep pushing harder and harder. Disney needs to grow every year, in order to please shareholders—so it can’t sit still for a minute. That whole corporation now depends on a small number of story franchises, and they must keep putting them out faster and faster to reach their financial targets.

That’s why Star Wars and Marvel won’t last anywhere as long as the Arthurian franchise, which thrived in a simpler day. The corporate owners are pushing too hard—serving up more and more lookalike films based on repetitive formulas. And it’s not just movies, but thousands of other brand initiatives based on the same fragile foundations.

Superman is strong, but not strong enough to hold up the share price when audiences lose interest.

Those living inside the corporate offices can’t avoid this eventual downfall. They’ve become addicted to prequels and sequels and spinoffs, and can’t reach their corporate growth targets without them. That alone will prevent them from stopping the train before it goes off the cliff.

Every morning they look in the mirror and tell themselves that fans will never abandon their favorite superheroes and the other cardboard characters on which pop culture financial empires are now based. And they’re so convinced that if you suggest that they try something smarter, deeper, more true-to-life, they will laugh at you. Audiences aren’t that smart, they will respond. They just want simple escapist entertainment, and the more predictable the better.

But that’s why the purveyors of pop culture should learn from the death of the Arthurian franchise around the year 1600. The audience did want something smarter, deeper, and more true-to-life. And that’s what they got from the novel. Once they had a taste of it there was no turning back.

By the way, if Netflix or some other competitor really wants to kill Disney, they ought to study that whole period from 1600 to 1800. In particular, they need to pay attention to Cervantes and Don Quixote.

If they did, they would learn to stop imitating the stale franchises, but actually turn them into targets of mockery and ridicule. That’s what Cervantes and Shakespeare did, and the strategy would work just as well today.

That might even be the next stage. Before the superheroes disappear, they first get turned into a joke. As far as I can reckon, they’re almost at that point already.

A number of years ago, I concluded that the superhero appeal came from the same place that made mythology so enduring. Replace the word "Superhero" with "demigod" and you've got Hercules. A little later, I discovered that Joseph Campbell said the appeal of Star Wars was because it tells a story we never ever get tired of - the hero's quest. King Arthur is a variation on that same thing.

Something may ultimately kill the profitability of DC, Marvel, Star Wars, and Disney itself, but these fantastic stories of epic characters on heroic quests will most likely never die. They might just move out of the movie realm and into VR once the bugs are worked out.

Time for Spaceballs 2?