Did the Blues Originate in New Orleans?

In his new book The Blues, musician Chris Thomas King asserts that the “blues was invented in the 1890s by Black Creoles in New Orleans.” That’s an extraordinary claim, although not entirely unwarranted, as we shall see below.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

King’s confident proclamation puts him in conflict with a host of other experts, each with a pet theory about the origins of the blues. Almost every regional blues style in the US has fervent advocates. And there are other possible sources for the genre outside the Americas.

I’ve written elsewhere about the pride of Texas blues advocates, who have offered strong arguments for the primacy of their tradition. I’ve also written a book about Mississippi blues, and though I’ve never claimed it was the birthplace for the idiom, I’m convinced that the blues was played at Stovall plantation in the Delta at least two generations before Muddy Waters made his first recording there in 1941. New York also has a key role to play here, if only because so many early hit blues recordings were made there—but my view (outlined in more detail below) is that blues flourished in rural areas long before it came to the major American cities.

Finally, we need to take seriously the claims that blues originated in Africa—as many have asserted. Samuel Charters traveled to West Africa fifty years ago to find these roots of the blues, and eventually abandoned the hypothesis. He reached the conclusion that African ingredients evolved into the blues, but this happened in the New World—hence blues is genuinely African-American rather than purely African.

I find his argument plausible, but I was shaken in my views by a snippet of a 1906 recording from Africa, uncovered by Dr. Lewis Porter, which clearly incorporates blues phraseology. It’s hard to judge from one track, which could be a random moment, but it’s a significant fact. Porter tells me that he continues to research this matter, noting that he has now listened to “over 200 recordings of African music made in the early 1900s” and surmises that the blues phrasing on the cited example may have been atypical and perhaps even unique. And, he adds, there’s a genuine possibility that the recording from 1906 "could have been influenced by African-American music, even at that early date." He will have more to share about this intriguing subject in the future.

And there are other theories about the blues, linking its origins to a whole host of other precedents: the Islamic call to prayer, vaudeville acts, Native American traditions, etc. Every one of the hypotheses has some evidence to support it, although not every case is equally convincing.

Given this complicated and conflicting evidence, I’m hardly surprised that King argues in favor of New Orleans. I’m merely surprised by the confidence with which he makes this assertion. Almost every claim he makes is in the face of numerous counterclaims from other knowledgeable parties with their own theories to support.

King builds much of his case around Mamie Desdunes, born in 1879, who was clearly playing blues in New Orleans around the year 1900. This is not a new discovery. Jelly Roll Morton told us about Desdunes during his Library of Congress sessions with Alan Lomax back in 1938. He even made a recording of her signature song, noting that it was the first blues he ever heard.

Other sources confirm Morton’s account. Bunk Johnson (1879-1949) also recalled performing with Desdunes, and cites that same song. Dates are elusive here, and unfortunately both Morton and Johnson sometimes played fast and loose with chronology in order to strengthen their own claims as originators of jazz. But archival research has filled in many gaps—so we now know that Desdunes’s trademark three-finger piano style was developed after an accident crushed her right hand at age fourteen. We can even date this event with precision because the accident was covered in the Times-Picayune newspaper on July 21, 1893.

This suggests (although it does not prove conclusively) that the oldest known blues song from New Orleans, “Mamie’s Blues,” was composed some time after that date. King provides useful perspectives on the pianist’s father Rodolphe Desdunes in his book, but his discussion of the latter figure as the “Father of Blues Thought” is more imaginative than empirical.

Other bits of evidence provide further clues to the date when blues first appeared in New Orleans. For example, the lyrics to “Mamie’s Blues” include this revealing stanza.

Two nineteen, done took my baby away.

Two nineteen took my babe away.

Two seventeen will bring her back some day.

Advocates for the primacy of Texas blues will point out that the 2:17 train mentioned here went to San Antonio and Houston. This train line flourished after the discovery of oil in Beaumont, Texas in 1901. These various facts and dates don’t undermine Desdunes’s significance, but they make it difficult to give her credit for performing blues before the period 1895-1905 when she was in her teens and twenties.

But there’s more evidence about New Orleans blues to consider before we can pass any verdict on this matter. The so-called spasm bands were almost certainly playing blues in New Orleans during this same period. These were street bands formed by youngsters, who typically relied on homemade instruments and performed for spare change. Jelly Roll Morton derided their musicianship, but confirmed that blues songs were performed on the streets of New Orleans in this era. “Even the rags-bottles-and-bones men would advertise their trade by playing the blues,” he recalled many years later, adding that you heard “more lowdown, dirty blues” from these street performers “than the rest of the country ever thought of.”

The oldest documented spasm band dates back to 1895—which is probably around the same time that Mamie Desdunes started performing. So we are seeing a convergence of data here—with most of the available evidence pointing to the late 1890s as a period when we have solid evidence of New Orleans blues.

“My considered judgment is that the blues does not fit the pattern of an innovation. It looks more like a tradition. There’s a huge difference between the two.”

The clincher in this argument comes from our knowledge of the activities of jazz pioneer Buddy Bolden around this same moment in time. Bolden is often lauded as the originator of jazz, but commentators rarely consider how much this innovator relied on the blues—long before W.C. Handy, the so-called ‘Father of the Blues’, had any notion that this kind of music even existed.

Surviving accounts of those who heard Bolden perform refer again and again to his blues sensibility. “Buddy Bolden is the first man that ever played a blues for dancin’,” Papa John Joseph told researcher Bill Russell in 1958—and Joseph, born in 1876, would have been around to hear (or hear about) earlier examples, if they had existed. Trumpeter Peter Bocage, born in 1887, told the same story about Bolden’s band: “He played a lot of blues, slow drags, not too many fast numbers. . . . [B]lues was their standby, slow blues.” Bolden’s first musical affiliations date back to 1894, according to his biographer Donald Marquis—so we now have a third intersecting point highlighting this same moment in time.

These may seem like ordinary facts, but anyone who knows the history of American music will understand how significant they are. There is no convincing evidence that the blues flourished in any other large urban area back in the mid-1890s. So, by my reckoning, New Orleans holds preeminence over New York, Chicago, Memphis, and other major cities—musicians in the Crescent City knew about the blues long before those other communities discovered it.

Is there more evidence we can cite in favor of New Orleans’s precedence? In 1957, Manuel Manetta told Russell about other early blues singers in New Orleans, and specifically mentions Ann Cook (born circa 1888), Mary Thacker (born 1891), and Alma Hughes (likely born in 1893). None of these singers can plausibly pre-date Desdunes—and Manetta was born in 1889, so his testimony is only reliable for the period after the arrival of Buddy Bolden on the New Orleans music scene. I could cite other examples, but they don’t help us validate blues in that city before the mid-1890s.

All this is significant and enlightening, but insufficient to prove that New Orleans was the birthplace of the blues. But it does suggest that blues was a significant ingredient in its commercial music scene at a fairly early stage. My considered judgment is that New Orleans was the source of “blues-inflected jazz”—but that’s a very different claim than citing it as the home of all blues. And as all the available evidence shows, early jazz borrowed ingredients from every imaginable source—military music, spirituals, opera arias, etc. The fact that an idiom showed up in a New Orleans jazz performance is no proof that it was invented in New Orleans.

How did the blues get to New Orleans? The preponderance of evidence points to its origination in rural areas, not urban centers. I’ve studied the process of how innovations emerge and are disseminated with some of the leading experts in the field—starting with Everett Rogers, back when I was at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business. Rogers, who coined the term early adopter, understood how innovations spread better than anyone, and his work influenced me profoundly. I even earned my living for a spell analyzing the diffusion of innovations for companies who paid me for my expertise. This is a precise, quantifiable science, and you soon learn how to recognize the patterns.

Innovations tend to happen in cities, but traditional practices flourish in more isolated areas. When a traditional practice migrates to a bustling city, it starts to morph and change—and this is precisely what happened to blues, in my opinion, when it arrived in New Orleans. As we have already seen, it got transformed into ensemble music for dancing. It got incorporated into jazz, and via that channel entered into the popular music of mainstream America.

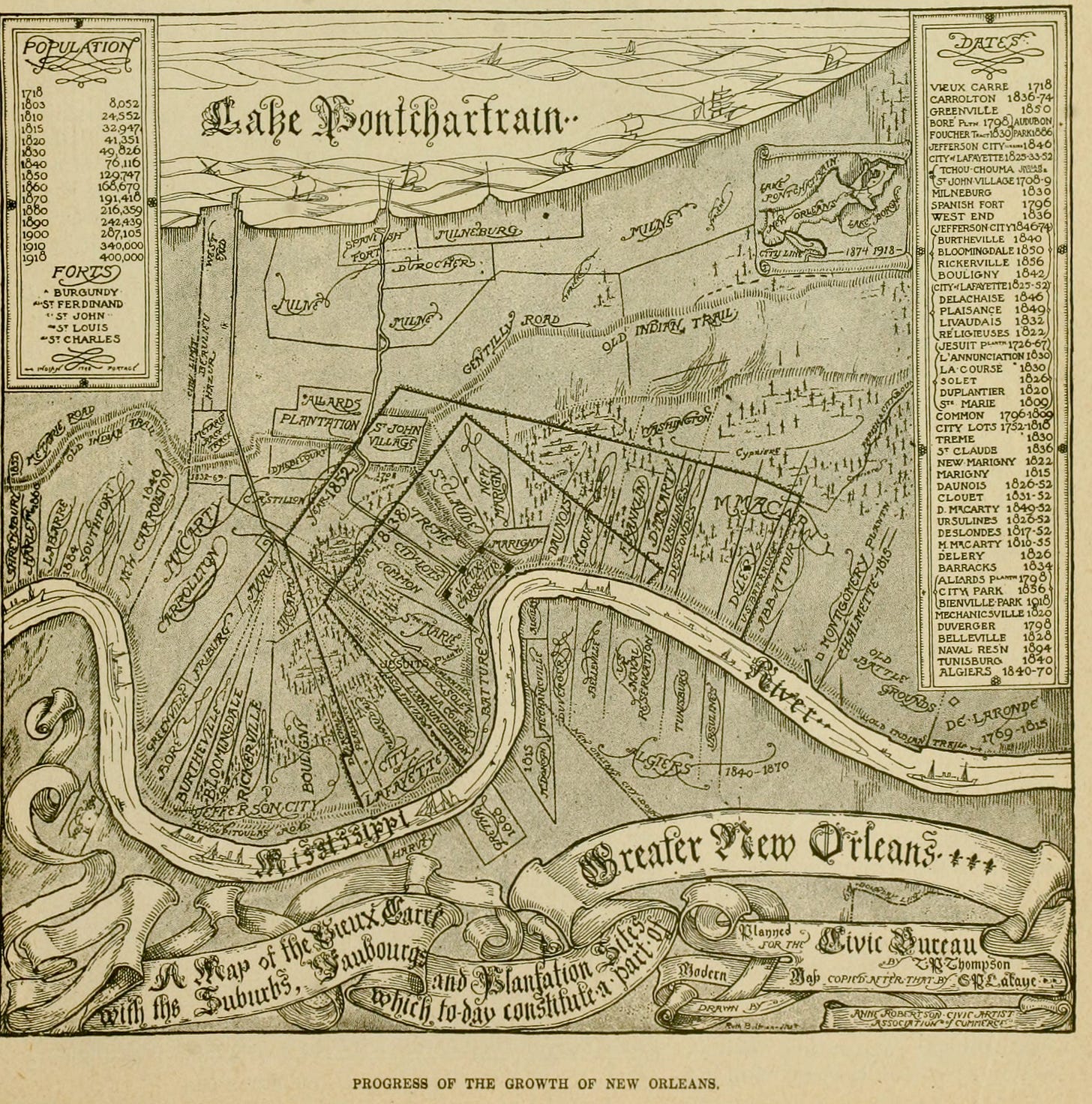

If you did a scatter plot on a map with a pinpoint for the birthplace of each early blues recording artist, you would find it resembles a map of African-American farming and sharecropping activities. The lyrics of early blues songs reinforce this connection with their frequent and repeated reference to various farm animals and rural practices. I conclude from this (and various other bits and pieces of evidence) that the blues is an old survival among African-Americans, with origins in agricultural communities—and the more these musicians were cut off from city influences, the better they were at retaining the blues. Some of the elements that went into these rural blues almost certainly had even older origins, going back to Africa, although it’s quite possible that these ingredients didn’t coalesce into actual blues music until they migrated to America.

One of the reasons why the blues flourished in Mississippi is because of its isolation. During the key years for the Delta blues, Mississippi had the lowest per capita adoption of radios, automobiles, and telephone lines of any state in the US. The very communities where the blues flourished were those most cut off from the rest of the country. A similar phenomenon can be found in many other locales where traditional blues flourished.

The blues-tinged music heard by Charles Peabody at Stovall Plantation in 1901 or 1902 was sung by a very old performer born before the end of slavery. This is one of the most significant differences between blues in New Orleans and other communities at the turn of the century. In New Orleans the music was associated with younger performers, while in the rural areas it was connected with older practices. That’s an important clue when we try to assess the migration of the musical style.

My assessment of the totality of this evidence suggests that the blues has very old roots, originating with performers who found new ways of playing African-inflected music in the New World—but typically in rural areas where they could remain immune to many of the influences linked to commercial trends in American music. The blues style eventually became urbanized in the closing years of the 19th century, and New Orleans was probably the first city where this style of music rose to prominence. It almost certainly arrived there as part of the larger migration from country to city—just as it later participated in the ensuing emigration of African-Americans from South to North. The idea that this path of dissemination went the other way around—with city musicians from New Orleans relocating to remote sharecropper plantations—is much harder to accept. That simply wasn’t the way people moved in those years.

Even so, I give New Orleans its proper respect. It was a major force in the history of the blues, and was way ahead of other big American cities. It launched blues-oriented jazz, and eventually shared that exciting sound with the rest of the US—and ultimately the whole world. Even it wasn’t the birthplace of the blues, those are extraordinary achievements that still reverberate in our musical culture.

It would be worthwhile to investigate the music school for enslaved people that existed in New Orleans prior to the Civil War. I understand we can trace most American music to descendants from that school's students who became the music teachers to the poor across the south after Emancipation. Students met on Sundays for decades at Congo Square, and it became a melting pot of French, Spanish, British and African oral tradition music.

A wonderful (and blessedly sensible) account. Many thanks.