Did Bach Draw on Native American Musical Traditions?

Here's a fascinating case study in how dirty dancing gets turned into the music of elites

In 1539, a poet in Panama named Fernando de Guzmán Mejía referred to a dance called the zarabanda. His poem provides very few details, and later sources are equally vague.

Some two decades later, a Mexican manuscript from Pedro de Trejo preserved the lyrics of a çarauanda, which is likely the same dance. In 1579, the Spanish missionary Diego Duran shared more information, describing the zarabanda as a “brisk and saucy” Aztec dance.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Then the same dance showed up in Europe—or at least a dance with the same name. We don’t really know how it happened. Maybe some Aztec dancers actually crossed the ocean. That’s a mind-blowing notion.

But we can’t even prove that the European sarabande is a direct descendant of its Native American predecessor. But whatever its origin, the zarabanda was well known in Spain by the mid-1580s.

Here it was typically sung to guitar music and castanets. A few years later, Cervantes refers to the zarabanda as “new at that time in Spain”—wording that suggests the dance had come from somewhere else.

Almost from the start, this dance stirred up controversy—and was even prohibited in 1583. That makes me all the more certain that the sarabande originated from the Americas—as I have documented elsewhere, there’s a long history of feared or conquered foreigners as musical innovators. But their new musical styles are initially attacked and suppressed, although they eventually enter the mainstream. This seems to be the case with the Aztec zarabanda.

Over the course of several decades, this saucy Aztec dance became the stately sarabande, beloved by Bach, Mozart, and others.

But this is hardly the only instance of Native American incursions into classical music. The chaconne, too, probably originated in Latin America before showing up in Spain in the late sixteenth century. Early source documents describe the dance as Peruvian, although some believe it came from the Caribbean coast areas of Mexico. As with the zarabanda, the chacona was attacked as sexy and disreputable.

That is hardly how these dances are viewed today. The sarabande and chaconne are squeaky clean categories of elitist European music—at least that’s how we are taught to view them. And to confirm this, I did a YouTube search. For ‘chaconne’ the first results are by Bach, and for ‘sarabande’ the first results are by Bach and Handel.

In other words, if you’re looking for dirty dancing, look elsewhere. The chaconne and sarabande aren’t even dances anymore—they are forms of classical music.

But how did Bach learn about these musical forms?

I’d love to tell you that Bach studied Native American music. And I bet he would have done so, if that had been possible, circa 1700.

Bach was much more worldly and cosmopolitan than you think (I plan to write about that topic some time, although not today). And I suspect he was curious about the music of the New World, given what we know about Bach’s attitudes. But no book devoted to Native American music appeared in print until 1882, more than a century after his death. That’s when Theodore Baker published his dissertation, based on field research with the Seneca tribe in New York.

There’s a curious fact here, however. Baker earned that PhD from the University of Leipzig—the same city where Bach flourished 150 years earlier. I’m sure they would have had many interesting conversations had they resided there at the same time. But during Bach’s day, there was no book or person he could consult about Native American music.

It’s much more likely that Bach discovered the sarabande by dancing.

Concert hall snobs have no idea how much Bach learned on the dance floor. Hundreds of his compositions refer to dance forms in their titles—and that’s not just coincidence. We know that at least three of Bach’s friends were dancing masters. One of his buddies, Johannes Pasch (1653-1710), even published two treatises on dance, one of them notates several elaborate French choreographies.

So we have every reason to think that Bach was a smooth operator in the ballroom. [Cue up the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack here.]

But if you study the literature on Bach, you might assume he relied mostly on mathematics or astronomy or some other scientific discipline to create his compositions. Douglas Hofstadter even earned a Pulitzer Prize for his book Gödel, Escher, Bach, which plays up these connections. But I’d skip the algebra and geometry if I were trying to get to the heart of Bach’s musical inspirations, and pay a visit to a dancehall instead.

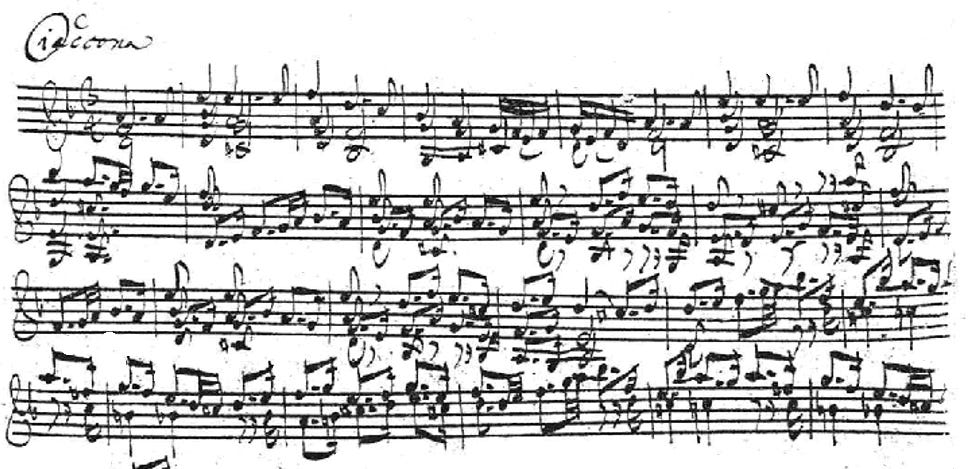

In all fairness, what he did with these dance forms goes far beyond what your typical EDM—or even IDM—artist delivers nowadays. Bach’s “Chaconne” from Partita No. 2 BWV 1004 (in which every movement derives from a dance) is one of the most profound works of the era, or any era for that matter. It is, in the words of violinist Joshua Bell, “not just one of the greatest pieces of music ever written, but one of the greatest achievements of any man in history. It's a spiritually powerful piece, emotionally powerful, structurally perfect."

Even earlier, Brahms remarked about this same piece:

“The Chaconne is for me one of the most wonderful, incomprehensible pieces of music. On a single staff, for a small instrument, the man writes a whole world of the deepest thoughts and the most powerful feelings.”

It’s likely that this work was written in response to the death of the composer’s first wife Maria Barbara Bach in 1720. Certainly the intensity and beauty of this work, as well as its duration—it’s one of the longest and most demanding solo works in the standard violin repertoire—suggest that the composer took a special interest in this composition.

I also have a hunch that Bach had danced chaconnes with his now dead wife, and those memories contributed to the emotions on display here.

So we give Bach the highest praise for this, and also recall the dead wife. But we also must acknowledge the dance that inspired it. And in turn, this lineage brings us back to Latin America, where it all started.

The whole process is emblematic of the cleansing process at work in musical reputations. The sinful and sexy dance of the outsider eventually evolves into a revered concert hall work among the elites of Western classical music.

In the case of the chaconne, this process took place over the course of around 150 years.

That kind of purification has happened before in music—and will happen again. It’s probably even happening right now, if only we knew where to look for it. Those new grooves are dirty dancing today but will be legit tomorrow.

And then the process starts all over again.

In Patrick O'Brian's novel "The Ionian Mission" British ship captain and violinist Jack Aubrey comes across some old sheet music in a London shop. Aubrey knows of J.S. Bach as "old Bach", and this passage details his reaction to the chaconne after playing through the score:

..it was the great chaconne which followed that really disturbed him.... There was something dangerous about what followed, something not unlike the edge of madness or at least of a nightmare; and although Jack recognized that the whole sonata and particularly the chaconne was a most impressive composition he felt that if he were to go on playing it with all his heart it might lead him to some very strange regions indeed.

A reminder of just how porous our cultural boundaries actually are. And, how cultural bits and pieces, shreds and patches, get passed around through the ages.