David Foster Wallace Tried to Warn Us About these Eight Things

This author, who committed suicide in 2008, is more timely now than ever before—for the worst possible reasons.

Rolling Stone magazine had not published a profile of a young writer in more than ten years. Literature was too boring for them. But journalist David Lipsky somehow persuaded his editor at Rolling Stone to send him on a book publicity tour with rising literary star David Foster Wallace.

But there’s a catch. The folks at Rolling Stone were convinced that Wallace was a heroin addict—and this would be the exciting hook in the story.

So Lipsky keeps prodding Wallace to talk about addiction and illegal drugs. Wallace, in turn, tries to avoid the conversation, but finally makes a shameful admission:

“My primary addiction in my entire life has been to television….That’s of far less interest to readers. Than the idea of heroin…”

Wallace knows this is an embarrassing situation. “Some addictions are sexier than others,” he notes. And his screen addiction is the least sexy of them all.

Please support my work—by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

So it’s not surprise that Rolling Stone lost interest in the story. Nobody cared about screen addiction back in 1996. The editors wanted something grittier and edgier. So they shelved the project.

But it came back to life after Wallace’s suicide in 2008. Lipsky turned his interview tapes with Wallace into a memorable book, and the book got made into an outstanding 2015 film The End of the Tour.

I encourage you to watch this riveting scene. The words are almost exactly what Wallace said in real life.

The release of The End of the Tour came at the same moment when smartphone sales were taking off, and youngsters around the world began experiencing their own high tech version of screen addiction. It was, as it turned out, far more widespread than heroin—and more profitable for the purveyors.

No drug cartel makes as much money as the screen-and-app companies. It’s not even close.

Those same youngsters are now showing up on college campuses, and we can begin to gauge the societal impact of a screen-driven life. It ain’t pretty.

So this is a good time to revisit what Wallace tried to warn us about thirty years ago. He was ahead of his time in the worst possible way, experiencing firsthand all the debilitating symptoms that now plague millions.

That’s why his writings feel so eerily contemporary. They read like commentaries on what’s happening right now.

Of course, Wallace knew very little about the Internet—he deliberately avoided it. He also refused to own a television. He understood how susceptible he was to screen addiction, and took drastic steps to reduce his exposure to all screens.

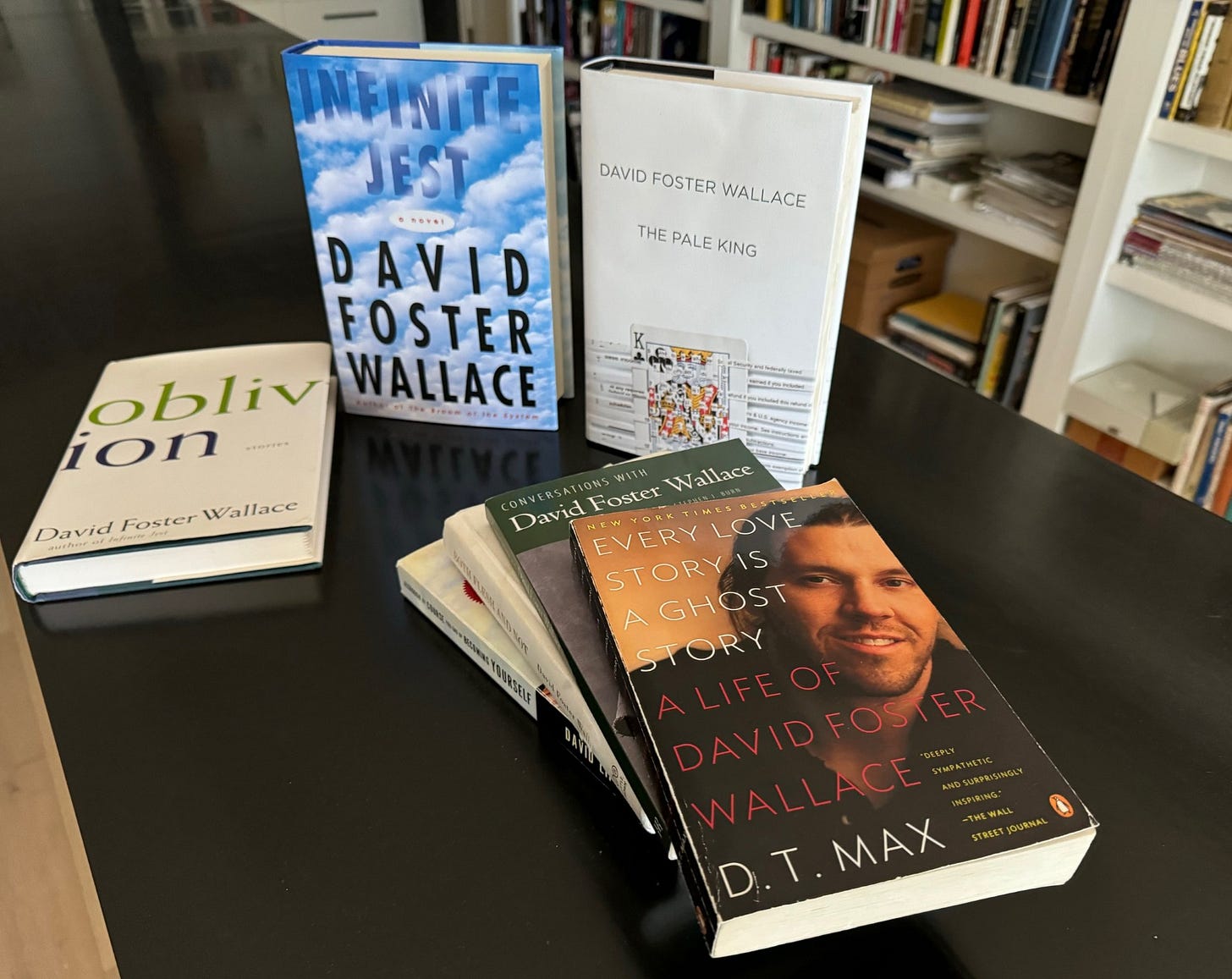

But he wrote about it—most tellingly in his huge novel Infinite Jest. The title refers to a film that is so addictive that people who watch it can’t stop. They literally watch it to death. It’s an infinite diversion, much like the endless scrolls on today’s social media apps.

He returned to the topic in his final book The Pale King, and also discussed it in interviews and essays. I’ve read through all of these including more than thirty interviews with the author. These allow me to put together a point-by-point summary of what Wallace tried to tell us.

We ignore his warnings at great risk.

(1) Screen technology will cause a crisis of loneliness, especially among young people.

In almost every interview, Wallace eventually talks about loneliness. It was a looming crisis, he insisted. But he was one of the first to link this to the ways we divert ourselves via screens.

Wallace told Lipsky that Infinite Jest was “about loneliness” and added:

If there is sort of a sadness for people—I don’t know what, under forty-five or something?—it has to do with pleasure and achievement and entertainment. And a kind of emptiness at the heart of what they thought was going on….

When asked why he wrote, he once answered: “I think what I would like my stuff to do is make people less lonely.”

(2) This will lead to widespread depression.

Wallace also knew this firsthand. He suffered intensely from depression. His inability to find a suitable treatment led to his suicide in 2008.

He knew that screen entertainments were his escape from depression, but they led to even more disconnection and loneliness—so ultimately the screens made things worse.

He called it a “stomach-level sadness” and a “kind of lostness” in his 1996 interview with Laura Miller. “Whether it’s unique to our generation I really don’t know,” he added. But his comments in other settings make clear his fear that young people were especially at risk.

(3) This will also happen at a larger scale. Society will grow more fragmented and disconnected.

As each person falls into an isolated relationship with a screen, larger communities begin to fray. Wallace anticipated a “new vision of the U.S.A. as an atomized mass of watchers and appearers.”

Instead of participating in a “community of relationships” we become locked into “networks of strangers connected by self-interest and technology.”

He wrote that in 1993, at a time when most people had no awareness of the Internet, but he might as well have been talking about Instagram, Facebook, and the other pervasive social media apps of our current moment.

(4) Screen technology promises to liberate us, but the reality is that it controls us for the benefit of others.

The most dangerous part of the screen entertainment is the illusion that it serves us. But the reality is that we actually serve tech platforms and their advertisers.

Those entities are very skilled at hiding their agenda. So we can stare at screens for hours every day without stopping to ask about the driving purpose behind the entertainment.

“Entertainment’s chief job is to make you so riveted by it that you can’t tear your eyes away, so the advertisers can advertise,” Wallace explained. He went so far as to describe this as “sinister”—surprising many who saw these things as harmless diversions.

He said that back in 1996. But the problem has metastasized since then—because the technology has gotten much better at control and manipulation.

(5) The people who control the technology work to hide their purposes and goals.

“They’re trying to lock us tighter into certain conventions, in this case habits of consumption,” Wallace told Larry McCaffery in 1993. “This is McLuhan right? ‘The medium is the message’ and all that? But notice that TV’s mediated message is never that the medium is the message.”

So screen media providers will never tell you the truth about the screens themselves. These interfaces appear—falsely!—as innocent and without agenda. But just follow the money trail, and it’s not hard to figure out what’s really go on.

The richest people on the planet are the ones who control our screens. That doesn’t happen by coincidence.

This is why the battle for transparency is so important as we deal with new tech—and why its purveyors are so resistant to even basic disclosure (for example, in the use of AI).

(6) Our survival will depend on our ability to remain independent of these forces.

If we abandon ourselves completely to the tech (as many now do), we become pawns in the corporate agenda to monetize us—at a tremendous cost in loneliness, depression, and social disconnection.

We only avoid this by taking personal charge of our life, based on our own agenda.

Wallace told Lipsky:

At a certain point we’re gonna have to build up some machinery, inside our guts, to help us deal with this. Because the technology is just gonna get better and better and better and better. And it’s gonna get easier and easier and more and more convenient, and more and more pleasurable, to be alone with images on a screen, given to us by by people who do not love us but want our money.

I remind you, again, that Wallace said this back in 1996. He had no experience with the internet or social media. But his sense of their future impact is uncanny.

Then he continues.

Each generation has different things that force the generation to grow up. Maybe for our grandparents it was World War II. You know? For us…[we] have to put away childish things and discipline ourself about how much time do I spend being passively entertained?

Then he adds: “If we don’t do that, then (a) as individuals, we’re gonna die, and (b) the culture’s gonna grind to a halt.”

Perhaps that’s an extreme statement, but we already see signs of both his gloomy predictions coming true.

(7) We don’t have many tools, but kindness and compassion will be the starting point.

We need to replace irony, sarcasm, and cynicism—which have contributed to our self-debasement—with softer, gentler attitudes. Cynicism is useful in criticizing, but is impotent when we need to build something better. Irony only destroys, never builds.

That’s why the age of irony (in TV, comedy, etc.) coincided with decline and degradation. The irony and sarcasm only made us feel better—we were above all this, it told us—as things got worse.

Wallace constantly criticized the ironic tendency in culture, and made a plea for more kindness. He knew that was unfashionable in hip literary circles, but he didn’t care. He thought that part of the solution was a willingness to appear unfashionable—that’s why he was so willing to share his own vulnerabilities and weaknesses in interviews.

He writes in Infinite Jest: “It takes great personal courage to let yourself appear weak.” But this nurtures compassion in a way that cynicism and irony never do.

After all, we are all weak—just in different ways and degrees.

(8) Art can help us heal.

He wrote his big books with the hope that they would help us find a way back to a more caring and connected world—but connected via people, not screens.

When asked about the goal of his vocation, he said something very unhip: “It’s got something to do with love.”

Can art really help all the lonely people? Wallace believed so, and focused his life’s work on doing just that.

The statistics tell us that there are more of those lonely people now than ever before. And we know from Wallace’s own tragic end what this kind of loneliness and depression can lead to.

What can we do to help? For a start, we can talk more openly about these things. Even that is a radical step—given how much the app-and-screen companies want to avoid those deep kinds of conversations.

So let’s be honest and admit the scope of the problems we’re facing. And the next step is to hold people accountable. These problems didn’t come out of nowhere, but were designed by powerful interests to achieve very specific, self-serving ends.

The perpetrators now need to take responsibility for the dysfunctional results.

And finally, on a personal level, we can embrace Wallace’s plea for more kindness and compassion. We don’t need anybody’s permission to do that, and we can start immediately.

I’d like to think some of us already have.

Awesome article. As a total DFWhead, I wanted to add a few more from his fiction, since I think that's become under discussed thanks to all of his amazing essays and interviews.

9. Depression Feels Like Truth

The short story "The Depressed Person" from Brief Interviews With Hideous Men is largely a demonstration of this point, explaining the various degrees depressed people go to convince everyone in their life that their worldview is purely fact-based, and how apt the mind it at convincing you it's right about everything, permanently.

10. Suicide Is A Constant Temptation--And Its Temptation Is Oblivious To Those Around You

"Good Old Neon" (from the story collection Oblivion), is a first-person monologue of Neal, a handsome, smart, successful man who struggles with impostor syndrome and feels like a complete fraud. He eventually decides to kill himself in a car accident and as the frame drops, we realize the story is actually a writing exercise from the perspective of David Wallace, who was desperate to understand why someone who had such a good life on the outside succumbed to suicide. Of course, this is only made more haunting by the fact that four years after the story's publication, Macarthur-winning best-selling author and happily married David Foster Wallace killed himself too.

11. Attention Is More Important Than Intellect

The Pale King, DFW's unfinished final novel, follows a group of Midwestern IRS agents to show, essentially, what it is like to be bored out of your mind. Chris Fogle, a drifting, distracted young man is treated as a hero as he struggles to find focus in the midst of paperwork, exams, and endless bureaucratic repetition. One scene stands out: watching As the World Turns in his dorm, Fogle realizes his own aimlessness isn’t just adolescent laziness, it's nihilism. He learns that paying attention, even to the dullest tasks, is a choice that creates meaning, and that heroism can exist in mundane work if you engage with it fully. Wallace repeatedly returns to these repeated forms, drills, and rituals to show that sustaining attention is the real work of life.

12. Surrender, Not Smarts, Leads To Survival

In Infinite Jest, DFW's magnum opus, Don Gately is a recovering addict, former burglar, and live-in staffer at Ennet House, a sober living facility. Early in the novel, he struggles to stay clean while facing constant temptation and the consequences of his past, including violent confrontations and the shadow of his own self-destructiveness. He eventually realizes that his intellect alone can never outsmart his addiction, it will only feed it. What enables his survival (and triumph) is embracing the simple, ritualized structure of AA: repetitive steps, corny slogans, routines, and service to others. Wallace shows that meaningfulness and resilience come not from cleverness or insight but from disciplined attention and humble surrender. Like all of his fiction, DFW's lessons here came from his own life: Infinite Jest was based on his struggles to get clean before writing the novel (and his amateur tennis career, of course!).

“At a certain point we’re gonna have to build up some machinery, inside our guts, to help us deal with this. Because the technology is just gonna get better and better and better and better. And it’s gonna get easier and easier and more and more convenient, and more and more pleasurable, to be alone with images on a screen, given to us by by people who do not love us but want our money.”

I think about this all the time. The more we tolerate it the easier it gets to accept.

Thank you for writing this.