Dave Hickey on Dolly Parton and Richard Pryor

I share passages from the expanded 30th anniversary edition of 'The Invisible Dragon'

I recently wrote about renegade critic Dave Hickey (1940-2021) in my essay on beauty. That article was entitled “The Most Dangerous Thing in Culture Right Now is Beauty.”

Hickey was an appropriate influence for my essay. He wrote bravely on beauty at a time (like now) when few critics dare discuss the subject. And Hickey, of course, was quite the expert on dangerous things—which often served as subjects in his articles or objects in his life.

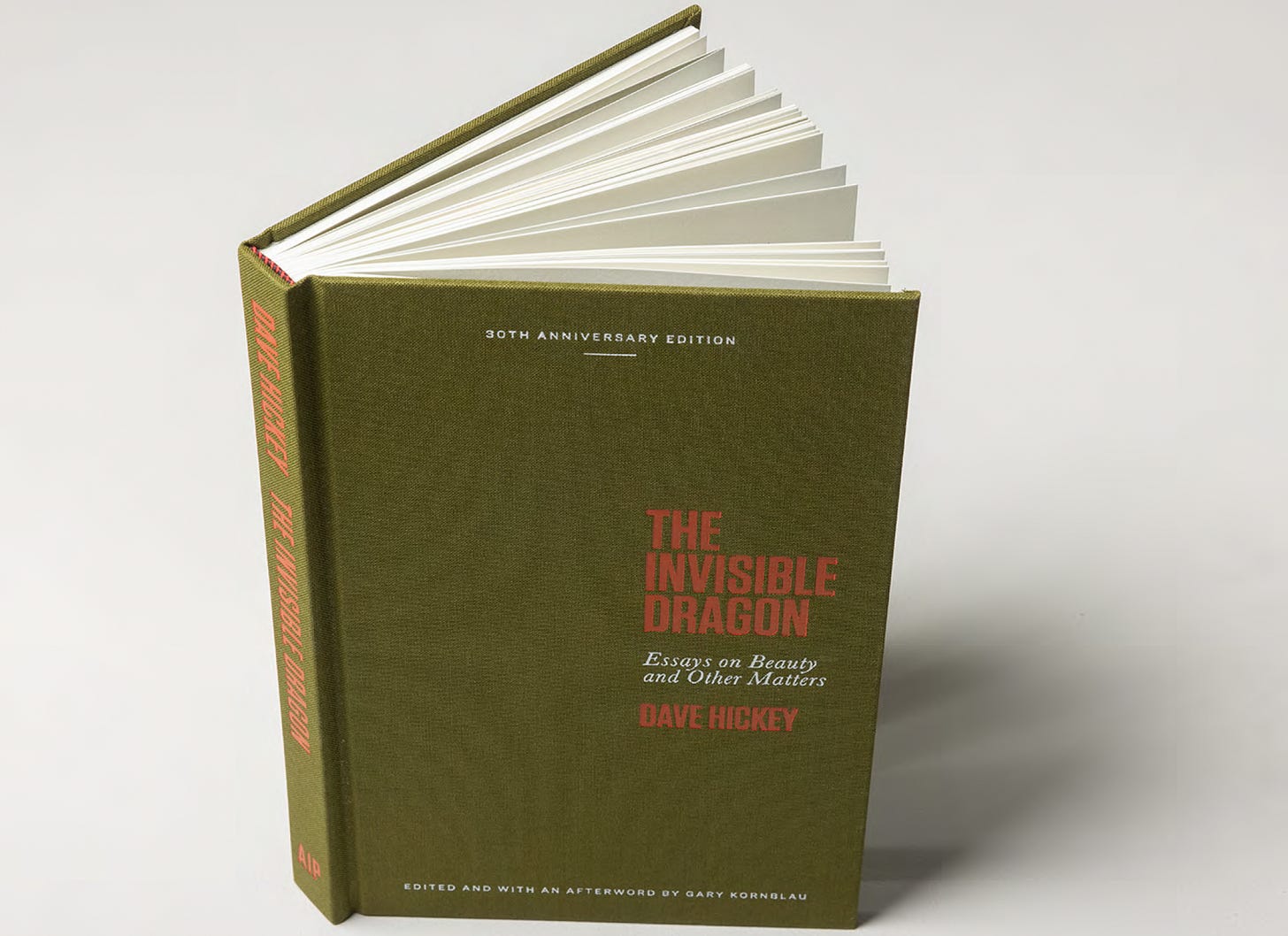

My timing, however, was especially good. That’s because the 30th anniversary edition of Hickey’s influential book The Invisible Dragon (1993) is coming out today. The new version, prepared lovingly by Hickey’s longtime editor Gary Kornblau, also includes additional essays—including the two articles quoted below on Dolly Parton and Richard Pryor.

I won’t try to sum up Hickey’s biography here—it resists quick overview. Where would I even begin? With his time writing country songs in Nashville? Or hanging out with Andy Warhol in New York? Or using his MacArthur ‘genius grant’ cash to play Texas Hold ‘Em poker in Vegas? Or running an art gallery in Austin?

I’ll let somebody else tell Hickey’s life story. I’ll just say that it deserves to be told.

Instead I will share some of the labels attached to him. I’ve heard Dave Hickey called:

“a cowboy-wannabe-slash-intellectual”

“the bad boy of art criticism”

“a chain-smoking white man given to all-black clothing”

“Texas-born, New York-adjacent, Nashville-infused”

“the Ronda Rousey of criticism”

“a cartoon villain”

“a whipping boy for the tenured minions”

“the philosopher king of American art criticism”

That ought to be a sufficient CV—better than anything you’ll read on LinkedIn—and enough to get a job, or certainly fired from one.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

I’m sure some readers of The Honest Broker have already picked up on ways Dave Hickey has influenced me. I’ve certainly learned from his stylish writing with its conversational tone, marked by raw honesty but full of fireworks and erudition. And I admire even more his willingness to take on the powerful interests imposing their sterile bureaucratic visions on the arts.

Hickey resisted the trend du jour, almost as a matter of personal integrity. He grasped what few critics understand—namely that the processes making or breaking artistic reputations deserve criticism even more than the artists themselves.

Few critics wrote with more authority about how we ought not give critics too much authority. Hickey pointed out—rightly!—that we always critique the history of earlier art by analyzing the institutions influencing and supporting it, but rarely scrutinize the behind-the-scenes power brokers who control our own culture.

Hickey embodies the role of critic as anti-critic in my cultural pantheon. That’s a holy vocation, a literal iconoclast going back to the roots of the word as a descriptor of those who clear away our false idols.

“The transactions of value enacted under the patronage of our new ‘non-profit’ institutions,” Hickey writes in The Invisible Dragon, “are exempted from this cultural critique, presumed to be untainted, redemptive, disinterested, taste-free, and politically benign. Yeah, right.”

Right indeed, and right on. A culture that gives a free pass to these ideologies of command-and-control creativity is a broken culture. I know because we’re living in one right now.

So The Invisible Dragon earns a place along other books that broke away from the ruling precepts of criticism—where Hickey can rub shoulders with Susan Sontag, Walter Benjamin, Roland Barthes, and George Steiner, among others. I’d love to see them all playing Texas Hold ‘Em at the same table in the Kingdom Come Casino.

I want to thank Gary Kornblau for giving me permission to share these passages with readers of The Honest Broker. You can learn more about The Invisible Dragon at the Art Issues Press website.

Dave Hickey on Dolly Parton

From “Dolly Triumphant!” (Country Music, 1974)

When the show was over, the curtain closed and the crowd stood up, but it didn’t leave. The promoters set up a long table in front of the stage, and when it was ready, Porter Wagoner, Dolly Parton, and Speck Rhodes came out and sat behind it, as nearly two thousand people formed a misshapen but orderly line to pass by. These weren’t flashy people, just folks from in and around Joplin, Missouri: farm families numbering in the teens; couples: she, semi-formal, he, in his service station uniform (Jim Bob stitched above the pocket); local honchos in roping boots, felt Stetsons covering army haircuts; preteen girls with disastrous complexions and autograph books; housewives, alone, in bouffant and pantsuits; old couples. They all filed slowly past the table, extending whatever they had to sign.

The people walked away clutching their autographs with strange smiles on their faces, especially the men. Since I had received one of Dolly’s smiles earlier in the evening, I knew the devastation they spread. But it was so nice: the people in their working clothes passing by the table, politely smiling, stars receiving them without condescension, thanking them for coming. It was so pleasant and decent that it upset my big-city reserve, and I walked out into the lobby. The concession stand was closed, so I lit a cigarette and read the names on a plaque honoring Joplin’s war dead from the First World War and Vietnam. I always read all the names on these plaques, one-by-one, war-by-war—it seems the least you can do. It’s not the same in the big city, but in a town the size of Joplin each of the names represents an empty place in the life of the town—the dead end of a family history, a family business—a small rent in the fabric of a community.

As I turned to walk back into the auditorium, I found myself thinking that, somehow, country music was about those names on the plaque, those people waiting patiently in line, and those three entertainers in spectacular costume signing their scraps of paper. All you get in Nashville is the prelude to this and its aftermath; this was the center. Down in front of the stage, Dolly and Porter were posing with a teenage girl while her friend fumbled with an Instamatic. The flashcube wouldn’t work; the girl with the camera was becoming steadily more flustered, and her friend was getting a little hysterical. She was taking up the stars’ time! People were waiting! Finally, she took the camera from her friend, made an adjustment, and handed it back. One more pose and poof! It worked. For an instant, Porter and Dolly were ablaze—with blinding smiles, sequins and blond hair, hovering like guardian angels around the frazzled teenager in her pedal pushers and sloppy skirt. People in the crowd applauded as the flash went off. They weren’t annoyed by the wait; they were glad the girl got her picture.

“I never really thought about it being work,” Dolly was saying an hour later. “I mean, they’re my fans. They’re who I work for. You know, they really care about you, at least country fans do. They’ll come up to you afterwards and tell you what they like and what they don’t like, as if you were a member of the family. They don’t tell you what to do, but sometimes they don’t like you to change, to explore everything you can do. It’s like the fans are parents who hate to see their child grow up—who want her to stay that pretty little girl. But they won’t stop loving you if you grow up right.”

I’m far too young to be so foolish, but I’m sitting in the coffee shop at Mickey Mantle’s Holiday Inn in Joplin and telling myself: Come on, boy! You’ve been to the fair and seen the bear. You’ve been to Terre Haute, Wilkes-Barre, and New York City. Are you gonna let a little yellow-haired girl turn you into silly putty? Huh? As if on cue, Dolly Parton looks up from her after-show dinner, unleashes a darling thousand-watt smile, and says: “Hon, you’re not gonna write down how much I’m eating, are you? . . .”

Dave Hickey on Richard Pryor

From “Plop, Squeak, Sniffle” (Art issues., 1999)

. . . The primary cultural benison of Pryor’s art, of course, has been the permission he issued with his liberating candor. He understood, early on, that content is nothing when heart is everything, that you can talk to anybody about anything, using any words you want, if they perceive the heart behind it. So, he talked to the whole world about Black culture in America from the heart—from the inside without excuses, apologies, or bowdlerization, explaining his project like this: “You know, I love Bill Cosby. Well, I was watching him one night when I thought, ‘Gee, he’s really good, but what if he just told the real truth about everything? Would he still be good?’” Pryor tried it. He told the truth about everything, confessed it all, and it was not the whole truth, of course. It was his own combination of heart, the facts, and lacerating candor, but we recognized it as the truth because he was good at it. A whole generation of artists, musicians, writers, and filmmakers, I think, recognized the breadth and depth of this permission and took it. This was his wonderful gift.

His primary gift to me, however, was his ability to portray everything from the inside—the scariness of it. To this day, I am shocked and amazed at the very idea that a human being would have the courage to walk out there on stage, to stand alone in the light with a sensibility that delicate and protean, with a sense of self so fragile and fluid that it can’t help but evanesce into the world around it and animate that world from within. That’s courage, my friend. And that is what I miss the most: the rich, effortless paganism Pryor evokes, the living world of living bodies he totally inhabits. Because Pryor not only chats with monkeys and German shepherds, he converses with God, with his dick, his heart, and his liver, with Malamutes, horses, deers, junkies, cops, lions, aunties, white ladies, evangelists, snot bubbles, and the wind off the lake in Chicago—and he chats with them about everything: mothers, murders, junk, shit, pissing, fucking, dreaming, presidential politics, and your first date.

Everything speaks in Pryor’s world and speaks through him. The gorgeous anxiety of watching him perform resides in the ease with which he slips into a character and the obvious difficulty he has finding his way back out. At times, returning, he seems drifty and confused, as if he were waking up from some oracular trance. Because Pryor is not just an inspired mimic like Robin Williams. The man really goes there, and, upon his return, you always sense that he was just barely tough enough to make it back. In my experience, the ability to just go is the gift of America at its edges, the product of its chaos, transience, and tumult. Creatures of tribes and communities, those with strong fortresses and walled subdivisions may cultivate their secret “selves,” may prune and shape their inner lives like handsome shrubs. Children of the drift just go—then try to get back. If you have ever played a sport, a game, an instrument, or done anything else that takes you profoundly out of yourself, you know this feeling. It helps you understand what a refuge the solipsistic blessings of booze and cocaine must have been to Pryor, because, in the realm of vertiginous affect, Walt Whitman is Emily Dickinson compared to Pryor, Ralph Nader is Pat Buchanan.

So, perhaps it speaks well for the democratization of cultural attitudes that a sensibility like Pryor’s, which in the nineteenth century would have been wholly segregated into the realm of belles-lettres, would, in our time, find expression in the louche medium of stand-up comedy and change the world a little bit. Or perhaps it doesn’t speak well of anything. Perhaps it speaks to the gentrification and isolation of “high culture” in our time, to its obsessive cultivation of fallow fields in well-fenced pastures, its ruthless pruning of bright children into tenured topiary. Chaotic America roars on outside the walls, so when I hear folks on C-SPAN complaining about the decline of art and literature in our time, whining about its loss of urgency and appeal, I think of all the loud songs and dirty stand-up routines that make the same magic through other means.

I think of all the children of the drift out there, bereft of privilege, who are just dying to do it—and who know from whence it comes. I think of Dickey Betts and Butch Trucks of the Allman Brothers slumped down in their first-class seats listening to Debussy on their Walkman, stealing moves, keeping it fresh. I think of Billy Joe Shaver, the prince of Texas songwriters, copping Yeats and singing about the pressure (“I’m just an old chunk of coal but I’m gonna be a diamond some day”)—and of my pal Will Jennings, lifting a verse-form we studied in Anglo-Saxon Lit for an Academy Award song (“Lord, Lift Us Up Where We Belong”)—of the rapper on the car radio whose cadenced narrative of “arms and the man” in the streets falls, magically, into Virgilian hexameters—and always, forever, I think of my brother in time, Richard Pryor, on that stage in New Orleans, brave as hell, doing Lewis Carroll in jive for a crowd of fucked-up Tapachulas. And I just think, Oh my!

You can learn more about The Invisible Dragon (or purchase a copy) at the Art Issues Press website. Wholesale distribution is handled by Distributed Art Publishers.

What I’m taking away from this piece is -- a person writing from the heart, about an author who wrote from the heart, about performers who performed from their hearts.

My god, I think I'll never write again. Ever, ever, ever. My heart is pounding, and I mean that literally. I feel as if I've been lifted into the air and the words up there are rarified and other-worldly and maybe not even real.

That is some damn fine writing and I can't believe I've never read Dave Hickey before. I'll have to proceed with caution now, and if I find the courage to read him at all, it'll have to be in small doses. Like this.

I'm still recovering, still trying to breathe. I don't even know what I'm saying.