Cruising for Classical Music in LA

A section from Dana Gioia's new book

I often mention my brother Dana here. And I don’t do it just because of family ties.

He’s my ultimate source on all matters cultural. Others feel the same. That’s why Dana has been called an “information billionaire” by Tyler Cowen, who adds that my brother is one of the few interview guests “who can answer all of my questions.”

I know what that’s like.

If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

Dana has been answering my questions since our childhood days. Even when I was a student at Stanford, I learned more from Dana (who started his MBA there the same year I entered as a freshman) than from my professors.

That’s why I often tell stories about my interesting brother here. And occasionally I share his writings too—with particular pleasure, because Dana is the most talented author in the Gioia family.

Today I have the privilege of publishing a section from his new book: Weep, Shudder, Die: On Opera and Poetry.

Official publication date is December 3, but you can already pre-order online.

Cruising for Classical Music in LA

By Dana Gioia

I have been fascinated with modern classical music since my teenage years. When my classmates were buying albums by Jimi Hendrix, Cream, and the Byrds, I borrowed their records so I could spend my money on Stravinsky, Hindemith, Poulenc, and Britten. I bought the few contemporary American operas that were available, such as Barber’s Vanessa, Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti, or Copland’s The Tender Land. I was lucky to have a high school friend who shared my passion for music and literature. Jim Laffan played trumpet. I played clarinet. He played piano brilliantly; I played piano. We explored music together. I had a vague dream of being a composer.

Fifty years ago, it was difficult to hear contemporary classical music, especially opera. Today the internet has created a cultural economy of unmanageable abundance. Nearly everything is one click away—available anywhere you can get a digital signal. A listener is no longer dependent on record companies or commercial media. Technology has allowed musicians to record and share their own performances. There is more music available on my cellphone than there was at the Stanford Music Library during my undergraduate years.

I grew up in a culture of scarcity. The shortage was especially keen in my rough-edged hometown in which the only cultural institution was the public library. There was no live music, theater, or visual art. The problem wasn’t merely finding the arts; we didn’t even know what to look for. There was no one to talk to, no older person who knew about these things to advise us. It took effort to hear new music, see a play, or find an unusual book. These difficulties, however, had an advantage. It made us value each encounter. As economics avows, scarcity increases value.

The problem wasn’t just the lack of a global distribution system such as YouTube. Back in the sixties little modern American music had been recorded, and less still had been released on commercial labels. The few pieces that made it to vinyl usually went out of print. Contemporary music was seldom broadcast on the radio. Orchestras and opera companies did not perform as many new works as they do today. We attended performances at colleges and conservatories. We searched for out-of-print recordings in used record stores. We found piano scores to work through on our own. Music didn’t come to us. We hunted for it. Searching was part of the experience.

I had one cultural advantage. I owned a 1955 Ford Fairlane, which I had bought for $100. Gas was twenty cents a gallon. Jim and I drove all over Southern California, which is admittedly something teenage boys don’t mind doing, to attend free concerts and performances. It was the age of high print-culture, each Sunday the Los Angeles Times listed every forthcoming concert in Southern California. Any concert within a hundred-mile radius was fair game.

Wordsworth and Coleridge talked about poetry and philosophy as they hiked the mountain paths of the Lake District. Jim and I had the San Diego and Harbor Freeways for our wandering. We discussed literature and music for hours as we drove to our distant destinations. My comparison is comic but only partially so. Young artists can only begin where they find themselves, be it late eighteenth-century Cumbria or mid-twentieth-century Los Angeles. Exploring and talking is what young artists do. They need to experience as much art as possible and then assimilate it by asserting, arguing, and revising their opinions. It is a brand of education, different from sitting in a classroom, and it is the best way to discover and develop individual taste. Oscar Wilde observed, “It is only an auctioneer who can equally and impartially admire all schools of art.” The rest of us have special insights, passionate loves, tenacious antipathies, and blind spots. To assume otherwise is a delusion. Some people have better taste than others, but no one’s taste is infallible. The important thing is to feel one’s true response and not subsist on a diet of second-hand opinions.

As a teenager, I saw a remarkable number of modern operas, mostly for free—The Love for Three Oranges, The Bassarids, The Rape of Lucretia, Die Kluge, La Voix Humaine, The Crucible, Amahl and the Night Visitors, Albert Herring, Dialogues of the Carmelites, and Bomarzo. I came to know opera without academic supervision. I liked The Bassarids so much, I went back to USC the next evening to hear it again. After all, it was free. (It was performed in English with its superb Auden-Kallman libretto.) I listened to the weird “world premiere” of Bernard Hermann’s Wuthering Heights—the composer’s self-produced recording was played on a local radio station. Hermann said a few words—perhaps by phone—and the announcer played the entire work. I bought the expensive box set of Hermann’s opera to support the project. I have hardly listened to it over the past half century—Wuthering Heights is a disappointing work—but when I see the old album, I still feel the frisson of its invisible premiere on my bedroom radio. Even disappointment can be sweet.

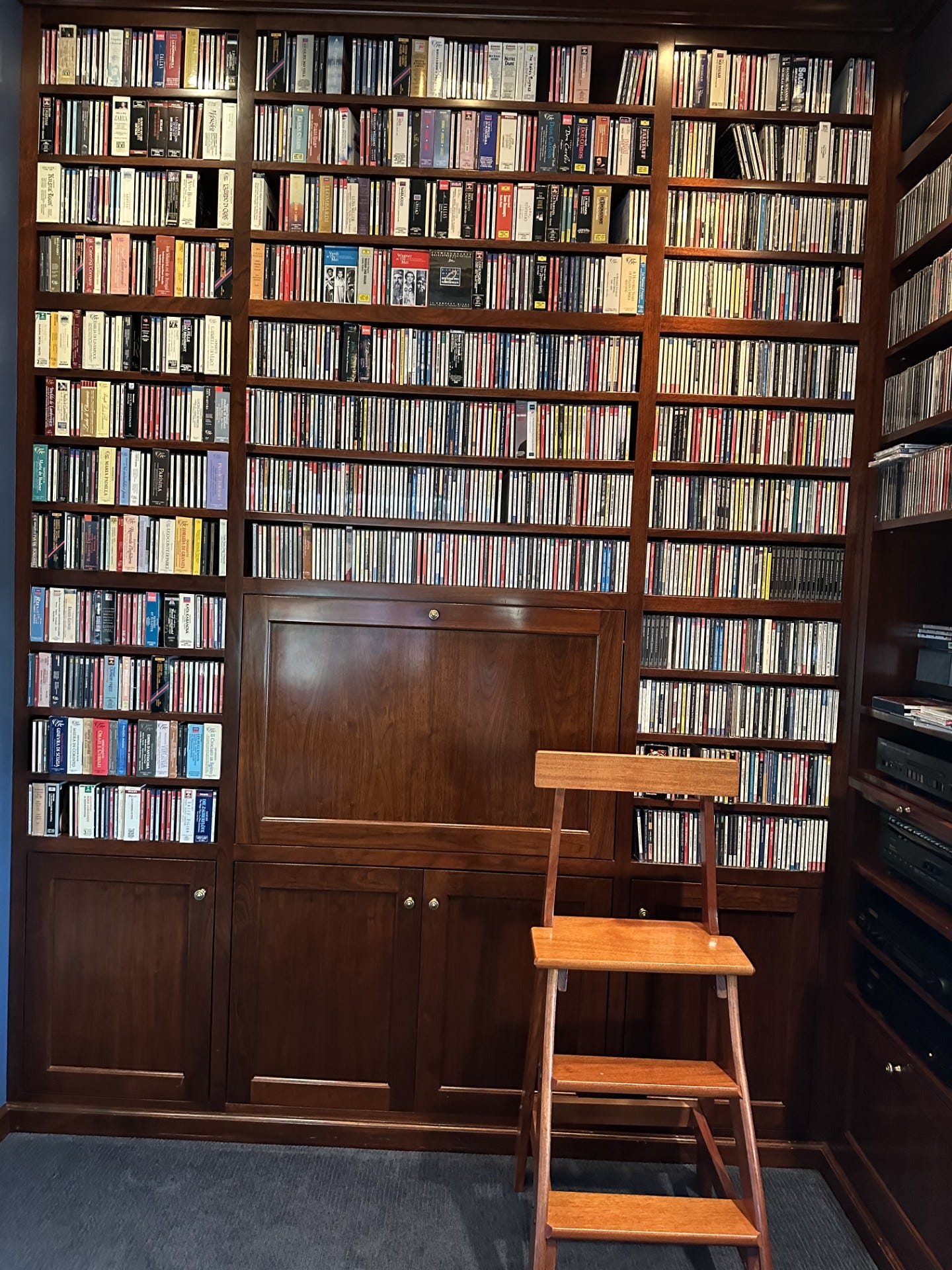

I’ve stayed engaged with contemporary music. As an adult, I’ve attended every production of modern opera I could manage. I have two walls full of opera recordings, especially modern works. For several years I worked as a classical music critic for San Francisco magazine. During my six years at the helm of the National Endowment for the Arts, I helped fund dozens of world premieres and revivals. In early middle age my involvement became more personal. Although I had long ago given up my notion of being a composer, I now began writing texts for composers. As a librettist, I’ve added five operas to the tradition. American opera is something I have heard, seen, and thought about. I have concluded that it is a puzzling and thwarted enterprise—as befuddled as current American poetry but with a bigger budget.

You can learn more about Dana Gioia’s Weep, Shudder, Die at this link.

I was resting on my sofa when "Nixon in China" by John Adams came on the tv. Woke me right up. I still like that one, now nearly 40 years later, especially when they find a proper soprano for "I am the Wife of Mao Tse Tung". That's a good aria.

I worked at a mainframe computer manufacturer starting in 1974 so Menotti's overrated and overplayed work will always be "Amdahl and the Night Visitors" to me. Those of you who know, know.

\(*_*)/ Ted, your family's talents are truly inspiring! I'm also a follower of Mike's Substack on AI:

https://intelligentjello.substack.com/

I'd love to hear more about your upbringing and how your parents nurtured your gifts.

Your insights would be invaluable!