Can We Stop Talking About "Rebranding" Classical Music?

I offer some skeptical views based on my own (often painful) experiences with rebranding

Can We Stop Talking About "Rebranding" Classical Music?

I need to say upfront that my bullshit detector starts ringing every time I hear the word rebranding. Not long ago, only big corporations used fancy buzzwords of this sort. But now they’re everywhere. Almost daily, I encounter people who tell me, in all seriousness, that they’re building their personal brand or working on an individual rebranding project.

When I first heard someone say this, a few years back, I thought it might be an ironic comment. Or perhaps a playful postmodern deconstruction of institutional semiotics. They must be making fun of marketing talk, no?

Sad to say, that’s not the case. I can’t peer into people’s souls, but I’ve looked into their eyes and listened carefully to their voices. I can attest to the fact that these people are dead serious about wanting to be a brand.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported newsletter. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. Those who want to support my work are encouraged to take out a paid subscription.

Me? I’m working on my personal BS detection project. That’s something worth having.

Everything, it seems, can be rebranded nowadays—first it was cattle, then it was tennis shoes, now it’s people. What’s next? Maybe a remake of The Wizard of Oz, with the Tin Man, the Lion, and the Scarecrow hiring Oz Consulting to do a brand redesign? If I only had a brand!

It’s just a matter of time, before your children or your pet dog show you their new logo and mission statement. Are there any limits to this corporatization of private life?

More to the point, can you rebrand a music genre or art form? And, if you can, should you?

Almost every music genre seems to be undergoing a crisis of confidence right now, accompanied by demands for rebranding. It’s happening in jazz and country and hip-hop and a bunch of other genres. But the anxiety seems the most acute in the field of classical music.

Certainly there are no shortage of issues in classical music—from abuse scandals to a hidebound repertoire that barely changes from decade to decade. I take these matters seriously. But are they really a branding problem?

“I once got involved with a $100 million business that was shrinking, and decided to change its name. A year later, the business was still losing customers, so it changed its name again. By the time of its third name change, there wasn’t much left to salvage. . . . They rebranded themselves into oblivion.”

The “experts” have few doubts about it. Consider some headlines:

Classical Music Should Rebrand to Appeal to the Young, says Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Chief

New Movement Launched to Rebrand ‘Classical Music’ as ‘Old Popular Music’

But how do you rebrand classical music? San Francisco Symphony recently gave us a glimpse of the playbook. This organization pulled out all the stops on its rebranding project—even adopting an animated logo and bold new font.

Here’s the font—which is named “ABC Symphony.”

Here’s the logo:

Pretty cool, huh? To be honest, I’d have opted for something more akin to Saul Bass than Looney Tunes. But maybe I’m not the right demographic.

Not to be outdone, the Brooklyn Symphony Orchestra has an animated logo with its own musical accompaniment. Please don’t call it a jingle. It sounds more like an orchestra tuning up.

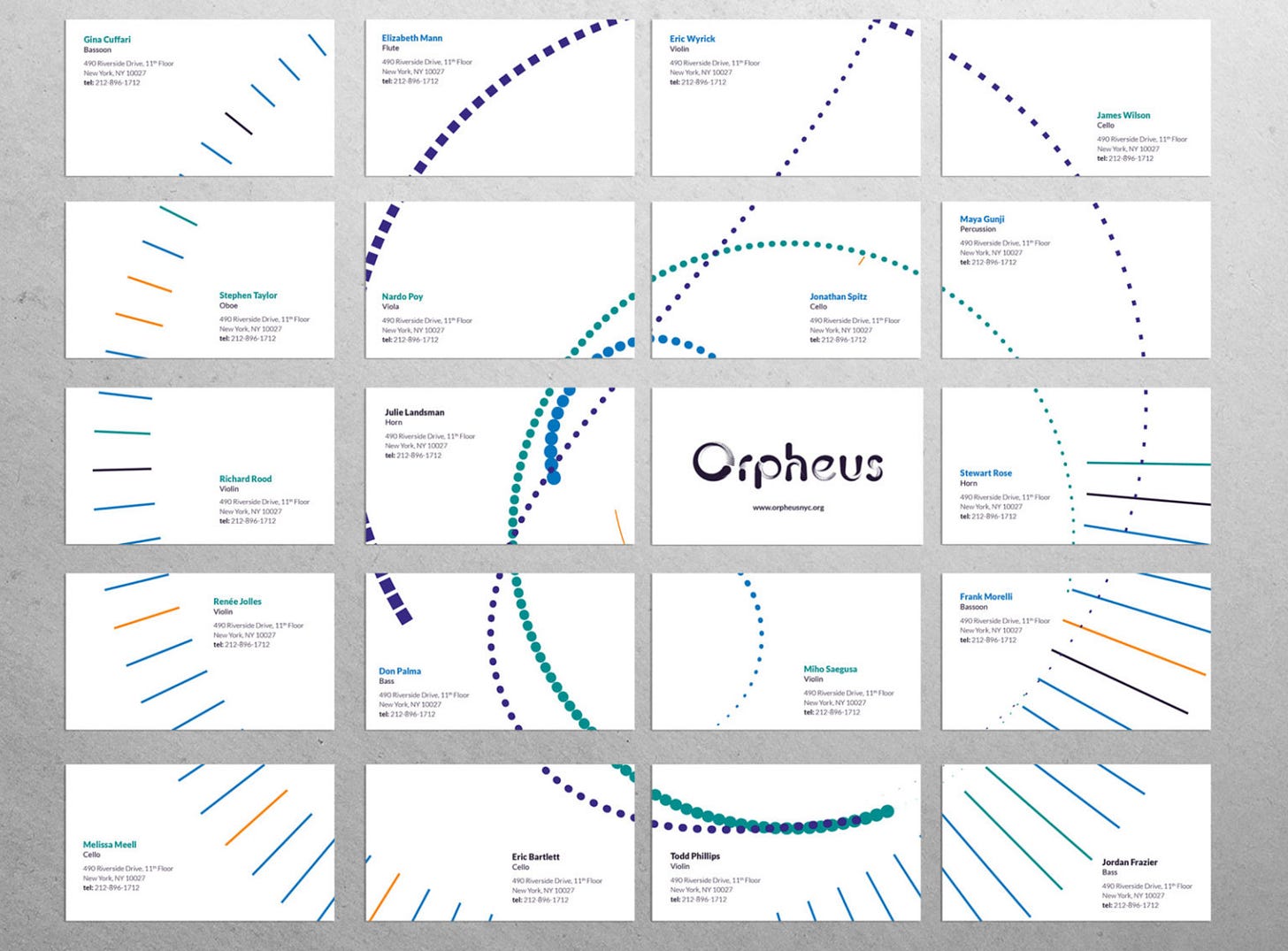

Circles and curves are especially favored as symbols. I’m not sure what they symbolize—unity? inclusiveness? circling the wagons against attackers? But they seem essential to the rebranding of classical music.

But nothing can match the ingenuity of the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra in using circles and curves. If you lay out the business cards of the orchestra members, it looks like this.

I’ll admit, it’s clever.

But surely the rebranding of classical music is more than just a logo redesign? Or laying out business cards like you’re playing solitaire. Rebranding classical music has to cut deeper. That would seem obvious.

Yet if you search through the many news stories and press releases announcing the results of rebranding projects, you will see an obsessive interest in the logo. This is hardly restricted to the world of classical music. I’ve found that even many professional managers tend to think of a company’s brand as identical to its logo.

That simply isn’t true. The brand is the cumulative impact of everything an organization does. The logo is the smallest part of that endeavor. It’s like the lock on the bank vault, and shouldn’t be confused with the riches inside.

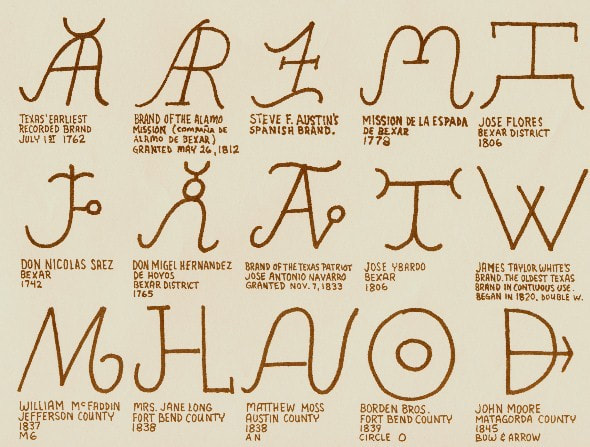

Even so, I can understand why so many people get confused about this matter. The origin of the term brand was an identifying mark burned into the flesh of livestock—the practice originated with the ancient Egyptians. So it’s easy to understand why people would confuse branding with a mark.

Even so, it’s absurd to put too much faith in those squiggles and swooshes. And certainly any rebranding of classical music has to aim higher. The issues in the field are daunting, and you’re bragging about circles and fonts?

I’ll let you in on a secret. I participated in many rebranding projects early in my career (more on that later). And there’s a reason why they look so ridiculous and accomplish so little. In every instance where I was an inside observer, the rebranding projects were undertaken by people with little or no authority in the organization, and most typically by an outside firm. These individuals have zero decision-making power. Their expertise is graphic design and marketing jargon, not substance. Anything more than that is above their pay grade.

If the real decision-makers made rebranding their top priority, they wouldn’t worry about squiggles. The wouldn’t sit around laying out business cards in patterns like a storefront fortune teller. Even more to the point, they wouldn’t call it a rebranding project. They would be practicing leadership, not massaging an image. They would be making hard choices on priorities. They would be hiring a team of people who were committed to genuine change, not spin and buzzwords.

In other words, true rebranding doesn’t even use that term. It has no need for marketing speak. More to the point, it has no time for it. The people making it happen have too many other pressing priorities.

As I have described elsewhere, my day gigs in my early years frequently involved high-stakes projects in Silicon Valley and overseas, and I eventually came to view rebranding projects with extreme skepticism. Heaven knows, I saw enough of them. I once got involved with a $100 million business that was shrinking, and decided to change its name. A year later, the business was still losing customers, so it changed its name again. By the time it embarked on a third name change, some months later, there wasn’t much left to salvage. It was now a tiny company. But they still did one last name change before disappearing, leaving behind almost no trace.

They rebranded themselves into oblivion.

It would be laughable, if it wasn’t for all the people who lost their jobs.

In the aftermath, I became an ardent opponent of rebranding. I always advised against changing names of companies or products or services—because this destroyed customer loyalty and brand equity. I managed dozens of corporate acquisitions back in those days, and in every instance argued that the acquirer make no change to the acquired business’s name and image. (Advice that was rarely received with enthusiasm—because what fun is it to buy a company if you can’t slap your name on it?) And I fought with particular vehemence against any fixation on logos, which in many situations seemed to border on a quasi-religious fetishization. I cautioned that time and energy devoted to these matters almost always distracted attention from more pressing matters.

I even lived through this firsthand as a CEO (albeit on a very small scale). In the late 1980s, some venture capitalists convinced me to launch a jazz record label with headquarters in Palo Alto, and generously gave me ample funds to make it happen. (There’s a whole story there, but it will have to wait for another day.) One of the first things I needed was a logo. I was referred by my VC friends to various firms that specialized in that very service. They each told me the same thing: I needed a corporate identity project, which would cost at least $25,000.

What did I do? I told the design firms that I wasn’t interested. Instead, I hired a part-time graphic designer to make me a logo. I think I paid him $300. That was my branding project. (By the way, he later won a design award for the work he did for me.)

Needless to say, this wasn’t how things were typically done in Silicon Valley. And my anti-branding views frequently met with pushback. Yet my ingrained skepticism was almost always validated by subsequent events. In particular I learned the following (often painfully, by observing failures and collapses):

(1) Rebranding is usually practiced by struggling or incompetent enterprises. In the short term, this vacuous project creates a burst of enthusiasm and optimism, but the long term impact is negligible. In many instance, it’s even destructive, because you’ve just thrown away any value your previous imaging possessed. It’s shocking how often these projects lead to further rebranding, ongoing decline, and sometimes even collapse.

Consider the case of the KGB.

It hardly needs to be said, but let’s say it anyway: The problem here had nothing to do with branding. And rebranding wasn’t going to solve it.

(2) Rebranding is typically pursued as a substitute for making more difficult decisions—namely, the bold moves that might create genuine change and improvement. When leaders lack the courage or confidence needed to pursue real change, the more likely they are to launch a rebranding project.

(3) The more someone talks about rebranding, the less likely they are to grasp what really needs to happen. Transformative change has little in common with messaging, graphic design, and marketing speak.

(4) The real strength in a brand is based on substantive actions, not messaging (and certainly not squiggles). That’s become increasingly clear in recent years with the rise of brands that achieve dominance while spending almost nothing on marketing and TV advertising. Amazon became huge without a TV ad campaign. Starbucks grew to dominance while spending next to nothing on advertising. The same is true of Google, Netflix, Facebook and almost every other mega-success story of recent memory. In other words. . . .

(5) If you make the right decisions, the brand takes care of itself.

And what about music? Here’s the bottom line: Classical music faces many problems—but constant talk of rebranding is itself one of the problems.

The real need is to revitalize the repertoire; celebrate our traditions but also create fun and exciting new ones; make the performance situations less stuffy; reach into the community (and especially the schools); transform the entire experience of concertizing into something more thrilling and engaging; above all, inspire and change lives.

And the only way to do this is by focusing on the music.

As a reviewer who devotes hours each day to listening to recently released recordings, I know how much fantastic new classical music is out there right now—and it’s genuinely mind-expanding and enjoyable too, something that couldn’t always be claimed for the entrenched academic composition trends of the not-so-distant past. Yet I’m also painfully aware that almost nobody knows about this music, and the very institutions that should be showcasing it are caught up in other, lesser priorities.

I love this new music, but that doesn’t mean we need to apologize for Bach or Mozart or the cherished masterworks of the past. Music is not a competition. That’s one of the lessons of genuine diversity. But even the canonical composers of the past are more meaningful when they’re part of a vibrant practice that’s alive and flourishing in the present day.

How do we manage the trade-off between past and present? When I launched a jazz website some years back, I decided that my preferred balance was 50/50—half of the coverage would focus on current music, and the other half on the rich jazz heritage. Others might have different views, but I thought that was the ideal mix. And though classical music is different from jazz, with a much longer tradition, we won’t have a healthy art form if 80 or 90 percent of our attention goes to the same works that were programmed fifty or a hundred years ago.

Looking at the leading classical music institutions from the outside, I can only guess what causes the current dysfunction, but my hunch is that decision-making is too dominated by internal boardroom meetings, office politicking, and a deep-seated reluctance to do anything new and risky. I’ve also learned from personal experience that even the top people at leading classical music institutions often seem unaware of what’s happening right now in their own art form—caught up instead on media-promoted trends and fashionable names.

You shouldn’t be surprised by that. In many instances, the heads of these organizations were hired for fund-raising skills or managerial expertise, not love of the music or deep knowledge of the art form. Given that gap in their background, maybe they should be out listening more, and rebranding less.

The first step is to put away the squiggles, circles, and fonts. Forget about finding a new name that will fix everything. Focus on the music. It’s why we went into this field in the first place. It’s why we stay, and why the audience comes and sits down in our expensive plush chairs. Even when the music is the problem, it’s also the solution. When we forget that, no amount of rebranding can help us.

Hey Ted, you gave me a great idea. I will rebrand myself as 48 years old.

Terrific observations about rebranding in general. As an ex-business librarian I have been a close observer of them in the business sector. And I saw the same problems in the nonprofit organizations I worked for.