Brian Wilson Is My Brick

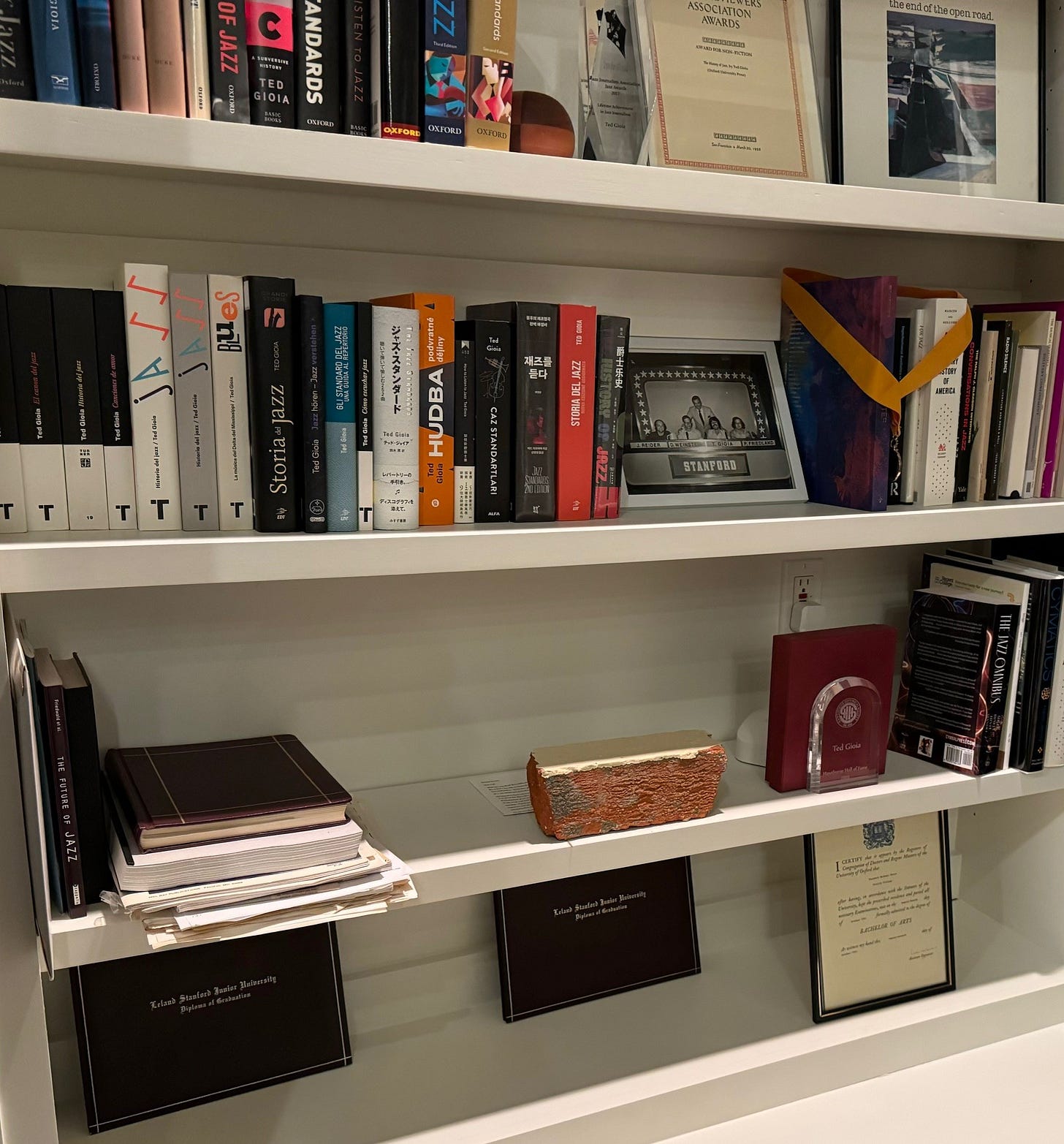

I keep a brick on display in my home. Visitors are puzzled to see it, especially because it holds a place of honor.

The brick sits among the milestone markers of my vocation—and enjoys a central position above my college degrees.

I cherish that brick. It comes from the demolished building 19 of Hawthorne High School in Hawthorne, California.

That’s my high school. And it’s Brian Wilson’s high school too.

He wrote about our school in a song. You may have heard it—it’s called “Be True to Your School.”

That’s not one of his better songs. But it hardly matters.

This brick is my way of keeping true to my school. It’s also a tribute to my roots and working class origins. It reminds me of where I came from.

And I don’t ever want to forget that.

I learned a lot at that school, but most of all I found myself. Sometimes it was a painful process. But everything that happened afterwards in my whole blessed life is built on what I discovered there—about myself and the world.

I bet Brian and his brothers had similar coming-of-age experiences at Hawthorne High. In fact I’m sure of it—because they sang so many songs about that period of their life. Those songs will endure longer than even my lonely brick.

Something about youth and hope and disappointment and fleeting triumphs and the fear of failure are preserved forever in those songs. And not just for me and my buddies from Hawthorne High. It feels like the whole world became our soul mates and eternal classmates because of those hit records.

Years later, I was gigging with jazz musicians in England, and I was surprised at how their responses to the Beach Boys were similar to my own—although they grew up 6,000 miles away from the surfing spots of my youth.

We were all riding the same waves, thanks to Brian Wilson.

I’ve long wanted to write about Brian and what he meant to me. And I have tried to do so repeatedly—putting almost ten thousand words on paper.

But I can never publish it.

If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription (just $6).

I always feel that I’ve left out the most essential part. There’s something about how I connected with the spirit and fragility of Brian Wilson during my youth that I just can’t put into words.

I’ve been working on an essay called “Surf Music and Me” for more than twenty years. But every time I look at it, I feel frustrated. I make some small tweaks and changes, but it never says what I want it to say.

I’ve written other things about Brian, and they also sit unpublished on my hard drive.

Now that he’s left us, I’ve returned to those scattered texts. I’ve asked myself if now is the right time to release them.

But I still can’t manage to do it.

After I learned of Brian’s death yesterday, I kept thinking about this. I felt that I had to say something. But the best I could come up with was a short, ineffectual note.

The problem is that I keep writing about my tangible, physical connection to the Beach Boys. People like hearing those things. Brian and I ate at the same hamburger stand (but he turned it into a hit song). We went to the same beaches (but he turned them into another hit song). And so on.

But the real impact Brian made on me was a secret one. It happened in private—in my inner life. In my daydreams. Above all in my room—something else Brian somehow turned into an unlikely hit song.

He and I shared that desire for an inner sanctum. We knew how important it was to retreat into a quiet place where we could be alone.

I was a strange child. I didn’t fit in.

I knew it. My teachers knew it. My classmates knew it.

In third and fourth grade, it got bad. Real bad. I was often bullied. I’ve blocked out a lot of those memories, but on two occasions large gangs of children—my classmates!—waylaid me after school, and beat me.

There was nothing I could do. There were a dozen or so of them, but just one of me. I wasn’t much of a fighter anyway. They didn’t need to bring such a large crew.

I’ve never written about that period in my life. I don’t even talk about it. But I realized today that this is part of the actual story of me and Brian and surf music and all the things I struggled to express in those unpublished essays.

This may sound strange. But I really don’t blame the youngsters who harassed me. They were just kids, after all.

No, they shouldn’t have hit me. But I was an odd boy, and must have been unsettling to be around.

How could they understand me, if I didn’t even understand myself?

Fortunately I had my room. As soon as I got away from the bullies, I ran back there as fast as I could.

It was my safe space, just as it had been for Brian Wilson.

And, like Brian, I also had my music. Even back then I turned to the piano for consolation, for serenity. For a way to commune with myself.

Outsiders often think that the biggest perk of music is getting on stage and performing to acclaim. But for many of us, we’re drawn to music as a kind of healing meditation—as a way of finding wholeness in our soul.

I’m sure that was the case with Brian Wilson. I know it’s the case with me.

If I could have articulated what I felt back then, it would have sounded like the lyrics to Pet Sounds, especially Brian’s song “I Just Wasn't Made For These Times.”

I keep lookin' for a place to fit in

Where I can speak my mind.

And I've been tryin' hard to find the people

That I won't leave behind.They say I got brains

But they ain't doin' me no good.

I wish they could.

Each time things start to happen againI think I got somethin' good goin' for myself,

But what goes wrongSometimes I feel very sad.

Sometimes I feel very sad. . . .I guess I just wasn't made for these times.

Brian expressed my world with such raw honesty. How did he know how it felt?

Well, I guess he lived it too.

I know he did—because this same story keeps repeating in so many of Brian Wilson’s songs. His music returns, again and again, to this sense of being the odd kid, the strange child, the boy nobody understands.

Just hearing this expressed in a song felt liberating to me. But even better was how Brian Wilson turned this difference into his superpower.

Over time, his weakness became his strength. He succeeded in the music world because he heard sounds differently from everybody else. He wrote songs like nobody had ever written them before. While others were still composing tunes, Brian was constructing elaborate multilayered tracks—almost like putting pieces together in an infinite aural jigsaw puzzle—and inventing a playbook that record producers still study decades later.

Even the Beatles started imitating Brian. Others wished they could imitate him—but they couldn’t even begin to wrap their ears around what he was doing in the studio (that now was his room). It was just too different.

Like I say, difference became Brian’s superpower

Along the way, he could take a group of crack LA studio musicians and get them to play things they didn’t even know they had in them. He did the same thing with his brothers and dopey cousin.

Sure, they had talent, and their voices blended beautifully. But Brian created outlandishly creative melodies for them to perform—the jigsaw pieces now locking together—unlike anything on the radio, or anywhere else for that matter.

Just listen to these 50 seconds of unreleased music from the Pet Sounds sessions, and marvel at the magic he extracts from a family gathering. Here, as so often, he gets others to share in his expansive vision—but it all originates from those mystical soundscapes of his inner life.

I rarely got bullied after fifth grade. I was still strange—but I did a better job of hiding it. I learned how to put on protective armor in my dealings with the world. I even took pride in succeeding in challenging situations, despite my oddities.

Others helped me. They supported me. I’m grateful for that. I would not have been able to do any of this on my own. (There’s a lesson there—and I’ll talk about it at the end.)

So I learned how to leave my room, my sandbox. Brian had done it. Maybe I could too.

During my last two years at Hawthorne High I really flourished. Along the way, I decided that my different ways of seeing the world could be an advantage—but I used this skill cautiously.

I couldn’t be so far out that I went off the deep end. I needed to find a balance.

No, I would never really fit in—not in any totally comfortable way. I would never be just like everybody else. And sometimes that made me very sad, like the narrator of Brian’s song.

But I had my own thing going on. I was determined to nurture it. I wanted to see where it would take me.

And so my journey began…

And that’s the story about Brian Wilson and me that I can never quite put into words.

That’s because it can’t be reduced to the songs or music criticism. It’s about all the inarticulate things those songs stirred in me. And maybe in you, too. That because I’ve learned that many others have gotten that same feeling from Brian Wilson’s music.

For us, the Beach Boys aren’t about surfing. Or the beach. Or fast cars. Or any of that fancy stuff.

These songs are about growing up, and all the pain that comes with it. And about the things you gain by maturing, but also the things you don’t want to let go of—even if they set you apart.

You feel all those things in his music. Even when Brian performs for others, he’s singing for himself—drawing on what Shakespeare calls “such stuff that dreams are made on.”

This is about as psychically exposed as you can be while sitting at a piano.

I eventually found my place in the world by holding on to my different way of looking at the world. Many of you have played a part in that—you’ve embraced me here despite my Brian Wilson strangeness, and I thank you for that.

I thank Brian too.

[And I have to thank Susan Bierman King Joynt, who gave me the brick—she personally saved it from the demolition crew—and Konnie Krislock who taught me how to write in her classroom in Building 19, now sadly razed to the ground.]

They are all part of this story too.

I know that there are others like Brian out there. And not all of them can turn their differences to such advantage. Some only suffer from being different. I’d like to think that Brian speaks to all of us through his music. And he can still do so after his passing.

He was my brick. He can be your brick too.

He tells the people on the outside that their difference can be superpowers. And he also speaks to those on the inside—reminding them to nurture those oddballs who see the world differently. Even if just a little of that rubs off on us, we are the better for it.

I want to make one last comment here—and this is to parents. Or to teachers or any adult that deals regularly with youngsters.

You may encounter a child who doesn’t fit in. They aren’t like everybody else.

That’s worrisome as a parent. And it’s painful for the child.

But don’t be afraid. Don't worry, baby. Everything still might turn out alright.

Seeing the world in your own way is no fun at age 10 or 15 or maybe even 20. But it can be a great blessing at age 30 or 40 or 50. It can even be a game-changer. I know that, because it was true for me.

So many good things happened in my life because I could see things others didn’t see. But I didn’t realize that until I was quite old.

Your child might be like that. I know this kind of specialness is a gift for many musicians or artists or writers. It’s probably true for a lot of vocations, from comedians to entrepreneurs.

If you treat this difference as a gift, the child might too. And if you can manage to see it in this way, you’re already halfway towards making it so.

I’m sure Brian Wilson would agree. I think he already told us that—in his songs.

Ted, I feel you just wrote what you needed to write about Brian Wilson. Perhaps the reason that you haven’t published previous writings is that - forgive my sentimentality - “the universe“ knew that the right moment would be now. You’ve captured that magical commingling of the fragile human being that Brian was with his staggering genius. You have centred him to a physical and internal geography that you both shared. This piece has touched my heart at this time as we all honour Brian’s life and art and observe his passing. Thank you, Ted.

I just forwarded "Wouldn't it be nice..." to my teens. They regularly meet with their group of friends simply to sing (hymns, a capella pieces, folk songs) - this song seems right up their alley and a fitting tribute to Brian Wilson. Stories like yours keep his memory alive, as will a young generation who continues to sing his songs.