Audiences Prove that Experts Are Dead Wrong

Or why 'Abundance' is more than just a political agenda

Much of my work here is focused on anticipating the future of our shared culture—which is under threat in complex, interconnected ways.

In particular, I’ve tried to show that many of the dominant digital trends are causing great harm. But they are unsustainable.

So they will reverse.

Things will get better. And that will happen even though the forces aligned against creative vocations and human flourishing appear to be huge—so much so that many have given up hope.

Today I want to give an example of a reversal that is happening right now—but few have noticed. I’ll explain the shift, and then I will describe in some detail why this is happening.

This is very useful information for anyone working in the creative economy—or anybody who wants to live in a culture that supports artistic expression and the life of the imagination.

By the way, this article was initially planned as a paywall-protected analysis for premium subscribers. But I want to give wider visibility to these huge, hidden changes (which are taking place in shocking contradiction to the conventional wisdom). So I’ve decided to make this installment of The Honest Broker freely available to everybody.

If you like it, feel free to share it with others. Or consider taking out a premium subscription.

Please support my work by taking out a premium subscription—for just $6 per month (even less if you sign up for a year).

HOW CULTURES HEAL

By Ted Gioia

When I saw the numbers, I couldn’t believe them.

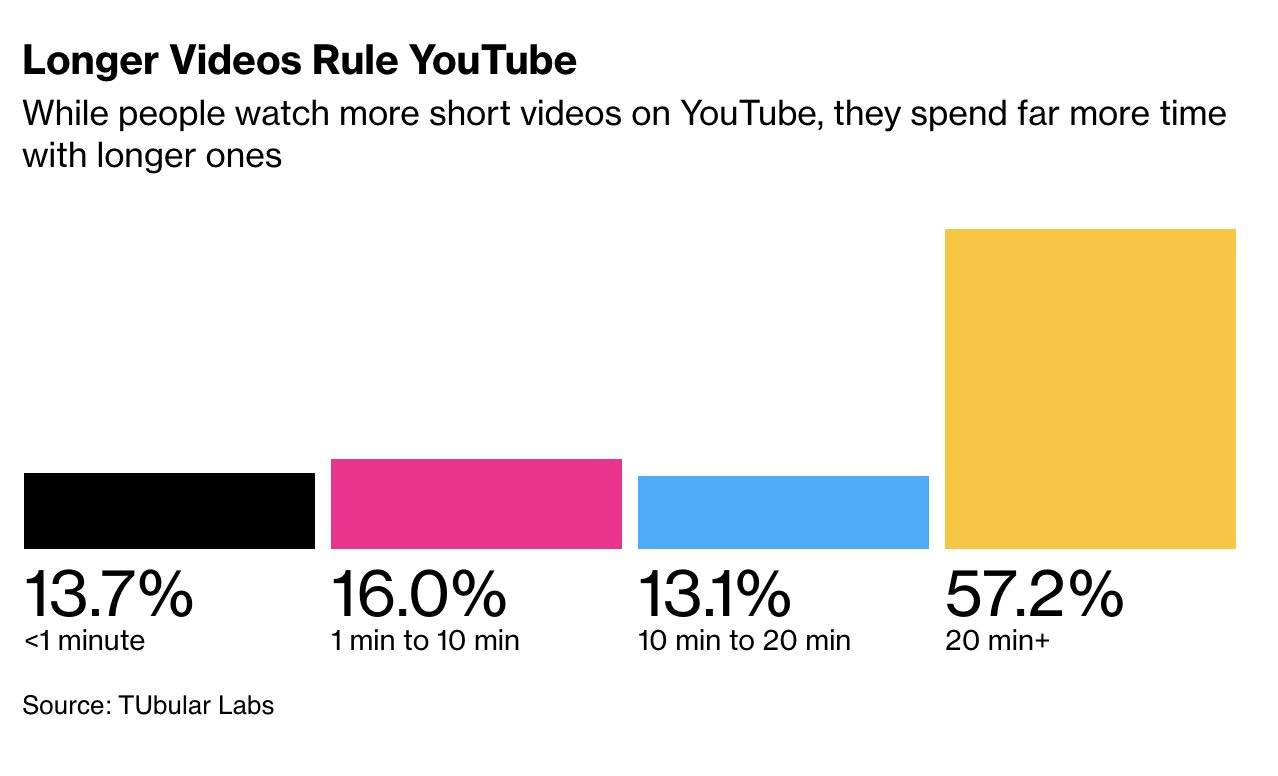

Every digital platform is flooding the market with short videos, but the audience is now spending more time with longform video—and by a huge margin.

Some video creators have already figured this out. That’s why the number of videos longer than 20 minutes uploaded on YouTube grew from 1.3 million to 8.5 million in just two years.

That’s a staggering six-fold increase. But even short videos are now getting longer. Social media consultants call this the “long short” format. Sometimes they are used as teasers to draw viewers to still longer media (often on another platform).

Movies are also getting longer. At first glance, that makes no sense—more people are watching films at home on small digital devices, where Hollywood fare has to compete with bite-sized junk from TikTok and Instagram.

“The rebirth of longform runs counter to everything media experts are peddling. They are all trying to game the algorithm. But they’re making a huge mistake….”

You might think that filmmakers would feel forced to compress their storytelling, but the opposite is true. They are learning that audiences crave something longer and more immersive than a TikTok.

At first, Hollywood insiders tried to imitate the ultra-short aesthetic, but they failed—sometimes in colossal fashion. (Does anyone remember the Quibi fiasco?)

Now they not only embrace long films, but happily release sprawling mega-movies longer than the Boston Marathon. Dune Two ran for 166 minutes—not even Eliud Kipchoge does that. Oppenheimer clocked in at 180 minutes. Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon lasted a mind-boggling 206 minutes.

The studios would have vetoed these excesses just a few years ago. Not anymore.

Songs are also getting longer. The top ten hits on Billboard actually increased twenty seconds in duration last year. Five top ten hits ran for more than five minutes.

Two of those long hit songs came from Taylor Swift—who has been a champion of longer immersive musical experiences, most notably in her insanely successful Eras tour. She set the record for the biggest money-generating roadshow in music history, and did it with a performance twice as long as a Mahler symphony.

These Swift concerts run for three-and-a-half hours (just like Scorsese at his most maniacal), and include more than 40 songs. They’re grouped in ten separate acts, each built around a different era in her career.

Ten acts? Really?

Even Wagner stopped short of that. But the Eras tour generated more than $2 billion in revenues. And all this happened while experts were touting 15-second songs on TikTok as the future of music.

I’ve charted the duration of Swift’s studio albums over the last two decades, and it tells the same story. She has gradually learned that her audience prefers longer musical experiences.

The New York Times complained about the length of her most recent album—calling it “sprawling and often self-indulgent.” It mocked her for believing that “more is more.”

It summed up her whole worldview with a dismissive claim that she has fallen in love with “abundance.” In fact, the Times opened its article with that accusation.

But I note that a year after the Times laughed at Swiftian abundance, the hottest topic in the culture is a book with that same word as its title. (Full disclosure: I’ll be doing a live Substack conversation with its co-author Derek Thompson in a few days.)

Abundance has dominated the New York Times non-fiction bestseller list for the last several months. Even more to the point, the word seems to tap into the public’s hunger for something bigger, deeper, and more expansive than it’s been getting.

Perhaps Taylor Swift understands the zeitgeist better than the New York Times.

In the culture arena, abundance is not just a highbrow concern. As the above examples make clear, the biggest winners in the new longform game are targeting mass market and lowbrow tastes.

Just consider those ultra-long podcasts by Joe Rogan. Or look at the popular fantasy romance novels by Rebecca Yarros—they clock in at 500 pages or more, but readers devour them like Joey Chestnut at a Fourth of July cookout.

Yarros’s new book Onyx Storm is the fastest-selling adult novel in two decades. It’s 544 pages, and weighs 29 ounces. That’s heavier than the javelin thrown by Olympic athletes.

Onyx Storm is part of a wider trend towards longer fiction bestsellers. Back in 2022, experts were complaining that the novels on the NY Times bestseller were shorter than ever—averaging 386 pages.

But that’s not true anymore.

I calculated the average length of the current fiction bestsellers, and they are longer than in any of the previous measurement periods.

Or look at all the longform writing on Substack. When I launched The Honest Broker, I assumed that readers would prefer shorter articles—but I soon learned that the opposite was true.

At first I was puzzled—but pleased. By now I just take it for granted.

Thompson’s (former) employer The Atlantic is another example of this revival of longform writing. Even as other legacy print media outlets shrink and disappear, The Atlantic can boast of an amazing turnaround.

Just three years ago, The Atlantic struggled with a $20 million deficit. Traffic was down. The magazine was laying off staff. Prospects looked bleaker than Jarndyce versus Jarndyce.

But the magazine is now profitable and attracting subscribers at a healthy rate—even after raising subscription prices by 50%. And The Atlantic is doing this in the most surprising way imaginable, namely by hiring top talent at high salaries and letting the writers tackle in-depth articles.

I recently got featured in an article in The Atlantic. And that article was almost eight thousand words—that’s longer than many novellas.

So like Substack, The Atlantic is achieving unprecedented success by totally ignoring the digital world’s obsession with short meme-oriented material.

Why is this happening?

The rebirth of longform runs counter to everything media experts are peddling. They are all trying to game the algorithm. But they’re making a huge mistake.

They believe that longform is doomed. They see that digital platforms reward ultra-short videos on an endless scroll. And they understand that this works because the interface is extremely addictive.

So short must defeat long in the digital marketplace. That’s obvious to them.

But all the evidence now proves that this isn’t happening.

Many media companies went broke trusting their advice. It was dead wrong—but many still haven’t figure out why.

Let me lay it out for you. Here are the five reasons why longform is now winning:

The dopamine boosts from endlessly scrolling short videos eventually produce anhedonia—the complete absence of enjoyment in an experience supposedly pursued for pleasure. (I write about that here.) So even addicts grow dissatisfied with their addiction.

More and more people are now rebelling against these manipulative digital interfaces. A sizable portion of the population simply refuses to become addicts. This has always been true with booze and drugs, and it’s now true with digital entertainment.

Short form clickbait gets digested easily, and spreads quickly. But this doesn’t generate longterm loyalty. Short form is like a meme—spreading easily and then disappearing. Whereas long immersive experiences reach deeper into the hearts and souls of the audience. This creates a much stronger bond than any 15-second video or melody will ever match.

All cultural forms create a backlash if they are pushed too far—and that is happening now with shortform media. People have digested too much of it, and are ready to exit for the vomitorium.

People now view anything coming out of Silicon Valley and the technocracy with intense skepticism and resistance. The pushback gets more intense with each passing month. This resistance has already killed the virtual reality market (despite billions spent by Meta and Apple), and will soon impact many other tech services—especially those based on turning the public into scrolling-and-swiping chimpanzees.

Longform isn’t like a drug. It’s more like a ritual. Instead of promoting addiction, it possesses a hypnotic power that creates an almost cult-like devotion among its audience.

Just consider the obsessive fandoms of Wagner’s Ring, Proust’s prose, Joyce’s daylong Dublin stroll, the Harry Potter novels, Christopher Nolan’s movies, DFW’s Infinite Jest, Beethoven’s Ninth, Taylor Swift’s concerts, etc.

No TikTok will ever generate that kind of passionate long-lasting response. They come and go. But longform fandoms will last a hundred years or more, and get passed on from generation to generation.

That’s why longform is making a comeback—in total defiance to the wishes of Silicon Valley and their scroll-driven strategies. Maybe that should be a lesson to them. Perhaps they should reconsider some of their other social engineering initiatives before they also meet with a painful reversal.

As someone who worked in Silicon Valley for 40 years but found her balance every weekend back in rural America, I have long believed that the experts are narcissists and will push anything if they can get rich on it. People the world over have allowed themselves to be manipulated by the sparkle of tech. Finally, the glare is hurting their eyes.

I hope this trend holds. On my YouTube channel, all of my short videos get about 1000-1500 views, while my longer ones rarely achieve more than 30 views. Personally, I think the longer ones are better, but the algorithm pushes the short ones into people's feeds. To even find one of my longer ones you have to search and scroll.