Are Harvard Graduates Better Than Harvard Dropouts?

Or how I spent $503,402 on college education

My wife and I have two sons. Like all children they needed an education—so we sent them off to college.

The price tag for their undergraduate degrees added up to $503,402.64. (I’m a numbers guy—I keep track of everything.)

And this is a number worth repeating: $503,402.64!

That’s a whole lot of education goin’ on. I wrote those big checks—but what did I really get for it?

I thought I’d earned a photo opp with the president of the university (or at least one of the 7,024 administrators)—like those photos I see in the news of other people writing big checks.

But no dice.

Wouldn’t it be better to set my sons up with a Los Pollos Hermanos franchise, or another small business? For that kind of cash, I could surely buy some profitable enterprises, and let them spend four years making money instead of spending it.

Son, here is your own coin laundromat—run it wisely.

We opted for college instead. I believe in the value of a well-rounded humanistic education. (Sometimes I think I believe in it more than the colleges themselves.)

But, honestly, is a high-priced degree really worth it?

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

I heard a story about a dropout back in 1976. I still recall it vividly.

I was a sophomore in college, and got the story from a classmate who played in my jazz band. He had a childhood buddy a couple years older than us—this buddy was super-smart, a real brainiac (as we called them back then).

But his buddy had recently started doing very strange things.

This boy wonder—a star student in high school, with outstanding grades and a world-beating SAT score—got accepted at Harvard. But he had now made a very stupid decision (at least by my judgment).

The buddy had gone off to Harvard, but decided to drop out after two years. He hadn’t been expelled. He left college voluntarily.

This story absolutely shocked me at the time.

I was 18 years old, and couldn’t even imagine the mindset of someone almost getting an Ivy League degree, and then walking away.

I had worked hard to get into a good college. The entire aspirations of my working class family were focused on me (and my siblings) getting degrees.

My father had been a servant (chauffeur for a wealthy real estate developer) for many years before opening up a small retail shop. My mother worked for decades as a telephone operator. They wanted something better for their children. So my success at college was much bigger than just me—I had my whole clan’s family pride to think about.

I might dream of dropping out and living as a musician. (In fact, I did dream of that.) But I’d never actually do it—that would be a huge mistake. My college degree would serve as the foundation for everything.

But I wanted to know more about this Harvard dropout, and asked my friend for details. What possible reason could he have for leaving college?

My friend said his buddy wanted to start a business. Something to do with computers.

Okay, this is back in 1976. So perhaps you have guessed the outcome of my anecdote?

My jazz musician friend had grown up with Bill Gates—Bill’s parents were family friends. And the young Bill Gates was the person he was describing to me back in 1976. But at that juncture, nobody knew who Bill Gates was—he had no fame or power or wealth.

He was just a dropout.

Back then, I assumed that this kid from Seattle was some kind of loser. He had worked hard (like me) to get into a good college but now was giving up.

I now see that maybe I was the stupid one. Even back then Bill Gates was setting up the business we know as Microsoft. A few years later he became the richest person in the world.

Nowadays, I’m not so shocked by this story. In fact, it makes perfect sense to me.

I’ve seen the pattern too many times. In 2005, Mark Zuckerberg left Harvard—also to run a business. You can call it Facebook or Meta or some expletive of your own choosing, but you can’t deny his financial success.

Consider this fact: If you were ranking the richest former Harvard students, Gates and Zuckerberg must be the top two—and they were both dropouts. I suspect that number three would be Steve Ballmer, who lived down the hall from Gates at Harvard. Ballmer did get his undergraduate degree before making his billions, but he dropped out of Stanford Business School after only a few months.

There are plenty of other wealthy people who are dropouts—Larry Page, Sam Altman, Larry Ellison, Michael Dell, etc. I could give dozens of examples. And if you study the careers of earlier American success stories (Thomas Edison, Walt Disney, Henry Ford, etc.) you see that this connection between innovation and dropping out is no recent development.

And it’s not just the United States. I recently read about billionaire Gautam Adani—the richest person in Asia. He dropped out of Gujarat University during his second year. He later became the second wealthiest individual in the world.

Those are too many examples to be mere coincidence.

Some of you will tell me money isn’t everything. What about arts and culture or (drum roll, please!) academic scholarship? How can you possibly become a great scholar if you drop out of college?

That might seem impossible, but it really isn’t. Just a short while ago, the Fields Medal, the most prestigious honor for a young mathematician, went to June Huh, who dropped out of high school to write poetry.

And dropouts in creative and artistic fields are the most successful of all. I could give hundreds of examples from the music world, but here are just a few:

Mick Jagger is a dropout from the London School of Economics.

Miles Davis left Juilliard after three semesters.

Bob Dylan dropped out of the University of Minnesota after one year.

Joni Mitchell is a dropout from the Alberta College of Art in Calgary.

Brian Wilson, who went to my high school, spent some time at El Camino, the local junior college, but dropped out after a year-and-a-half.

Jimi Hendrix dropped out of Garfield High School in Seattle, and formed a band instead.

Madonna dropped out of the University of Michigan and moved to New York to start a music career.

Taylor Swift never took a college class and stopped attending high school after tenth grade—because she was too busy recording and performing.

Frank Zappa dropped out of multiple schools.

Paul McCartney was accepted at a teaching college in Hereford, but started the Beatles instead.

“I ruined Paul’s life,” John Lennon later joked. “He could have gone to university. He could have been a doctor. He could have been somebody.”

Lennon, for his part, had more formal education than Paul—he attended the Liverpool College of Art, which is now part of Liverpool John Moores University. But Lennon got expelled because of his poor academic performance.

However, the campus now boasts a building named after its most famous dropout. It’s called the John Lennon Art and Design Building. They even showcased one of his drawings on the building’s facade.

Take a moment and savor the irony.

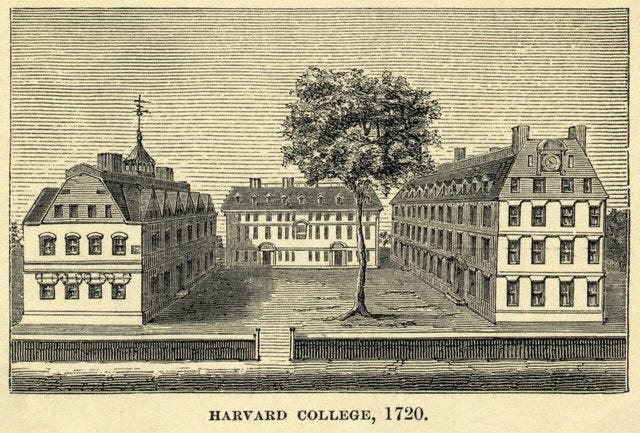

If I’d paid attention, I’d have noticed the power of dropping out even back in my own college days. I was an English major at Stanford, and the university was very proud of its most famous author: John Steinbeck. Even today, Steinbeck is the only former Stanford student to win a Nobel Prize in Literature.

But Steinbeck never got his degree.

The other great writer of that era with Stanford connections was Ken Kesey, but he constantly ran into hostility and rejection in Palo Alto. The head of the creative writing program Wally Stegner repeatedly rejected Kesey’s application for a fellowship. Stegner’s successor Richard Scowcroft was just as dismissive, stating that “neither Wally nor I thought he had a particularly important talent.”

Kesey had to use deception just to sit in on graduate writing classes. Denied a fellowship, he was forced to take menial jobs, including work at the Veterans’ Administration Hospital near the Stanford campus.

Here’s the best part of the story: Kesey got the idea for his breakout novel while working at the VA Hospital. You may have heard of that book, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest—later turned into a movie that won five Oscars.

It’s the most successful novel ever to come out of the Stanford writing program. But it only exists because the program directors punished Kesey at every turn.

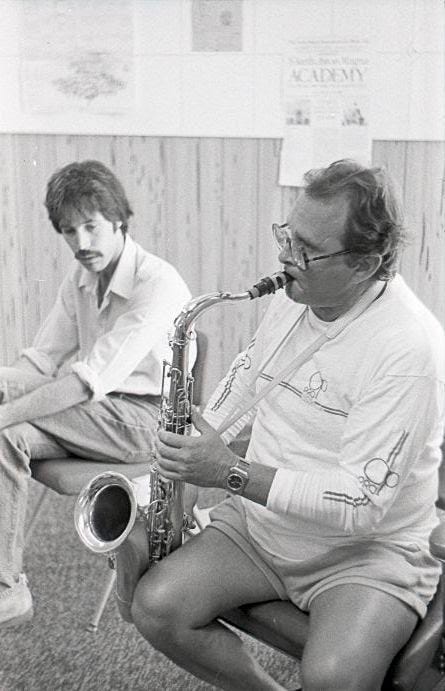

Years later I dealt firsthand will this bureaucratic backlash when Stan Getz joined Stanford University as an artist in residence. A wealthy entrepreneur offered to donate money to make Getz a professor, but it never happened.

Why?

Stanford administrators were horrified that Getz—who never finished high school—would have the title of professor. They refused to allow it. Artist-in-residence was the best they would do.

Dave Brubeck told me that he only received his degree in music after promising the dean (at the College of the Pacific) that he would never teach the subject. He later became the most famous graduate in the history of the college.

I’ll let you judge whether Getz and Brubeck had sufficient credentials to be music professors.

Now let’s take a look at famous writers—many of them dropouts, or never attending college at all:

F. Scott Fitzgerald dropped out of Princeton.

William Faulkner dropped out of the University of Mississippi after three semesters.

Doris Lessing’s education ended at age 14, when she went to work as a nursemaid.

Jack Kerouac dropped out of Columbia.

Ernest Hemingway never went to college, taking a job as a reporter instead.

Ray Bradbury never attended college.

Maya Angelou never attended college.

Samuel R. Delaney dropped out of City College of New York after one semester.

Cormac McCarthy dropped out of the University of Tennessee twice!

This is, of course, just a small sample.

But here’s the final twist—my own life showed me, again and again, how little I relied on my college education for my vocation. And this was despite my extreme focus on attending classes.

I spent almost a decade and huge sums of money—much of it borrowed in the form of student loans—to earn multiple degrees from elite institutions.

But I don’t have a degree in music—the field that became my vocation. And I never took a single course or lesson in jazz (my specialty) during my entire life.

I wasn’t a dropout, not even close. But it’s sobering to consider my life in retrospect, and see how much it relied on what I taught myself outside of the classroom. So I now have a very different view of college than I did back when I was a student.

My more mature view is as follows:

(1) A college degree is more about signaling your worth than about learning.

This is hardly a brilliant insight—many are now saying this. But when you’ve lived it yourself, it changes your perspective on everything.

People opened doors for me and gave me a chance on a few occasions because of my academic degrees. But what I did with those opportunities was mostly built on what I learned outside of college. It’s reasonable to ask whether a signaling advantage deserved almost a decade of my life.

There must be a quicker and less expensive way to send that signal. (By the way, there’s a huge business opportunity for an entrepreneur who creates that signaling alternative.)

(2) College provides inspiring role models—but they also exist in other settings.

I was blessed with a small number of teachers and mentors who taught me by example—and most of this happened at high school and college. There is no substitute for seeing greatness in the flesh at close hand.

But this can happen outside of college—my wife, for example, had those experiences working as a dancer and choreographer in New York. She learned more from her mentor Erick Hawkins than from any college professor.

Is college the best place for a young person to experience great role models in the current day? I have my doubts. And it doesn’t help when colleges spend most of their money setting up huge bureaucracies—my son’s alma mater has more administrators than undergraduates!—instead of hiring inspiring people with demonstrable excellence in their fields.

(3) Dropping out is a real option with genuine upside, but it’s not for everybody.

Let me put it as simply as possible: Many successes are dropouts, but few dropouts are successes.

I would advise against abandoning your education for simple reasons of avoidance—because classes are a hassle, tests are a bummer, etc. But if you have a genuine vision of your life and the skills to achieve it, college is purely optional. And perhaps even hazardous.

(4) As the college experience becomes more expensive and close-minded, the appeal of alternatives increases exponentially.

At what price does college become a bad deal? I don’t have an answer to that, but we must be close to a tipping point.

If I tried to replicate my formal education today, it would cost ten times as much. I would have student loans as large as the national debt of a mid-sized country. That’s just ridiculous.

But this kind of irrational endpoint results when a bloated bureaucracy increases tuition at more than the inflation rate every year—and continues doing so for a half century. The people running our major universities think they can get away with this because customers want impressive diplomas, and can be squeezed to an infinite degree.

But infinity doesn’t actually exist in human affairs. And unsustainable trends eventually prove just that, namely that they are unsustainable.

(5) The smartest people will increasingly bypass the system.

I can’t emphasize this enough. My advice to young people today is very different from what I would have said just 5 years ago.

I now tell them to find ways to work outside of bureaucratic legacy institutions.

If I were starting out as a writer nowadays, I wouldn’t waste time sending out manuscripts and articles as a freelancer (which I spent years doing). I’d work to bypass the system. Maybe I’d launch a podcast, or YouTube channel, or a Substack—or maybe all three.

Or I’d set up my own online courses. Or I’d form an artists’ collective. Or I’d start some other entrepreneurial effort where I didn’t need favors from tired pencil-pushers working in moribund organizations. The digital economy has given us a thousand ways to bypass the system.

Even if these institutions still have lingering prestige (or so I am told) from their past triumphs, that prestige is decaying with an ever shrinking half life

(6) Dropouts really do change society.

As someone who invested so much time and money in big-ticket credentials, that’s painful to admit. But I’ve seen too much to ignore the facts. I now grasp that people who are genuine visionaries know at an early stage that they can teach themselves, think for themselves, and manage themselves. Those are more valuable skills than any degree.

So maybe I didn’t drop out like my friend’s buddy at Harvard, back in the mid-1970s. But I wouldn’t laugh at the idea nowadays, the way I did back then. And if I had everything to do over again, I might drop out myself.

I couldn't agree more with your conclusions about the reverse-signaling involved in academic degrees. My father used to say that BS actually meant "Bullshit", MS meant "More of the Same" and PhD meant "Piled higher and deeper."

Harvard voted against offering Nabokov an associate professorship in Russian Literature after one of the incumbent professors asked the committee, "Do we really want an elephant teaching zoology?"

The greatest Shakespeare scholar, whose books I have but whose name escapes me, never earned a PhD. When asked by a student why he didn't just go ahead, submit his next book as his thesis, and get his Doctorate, he asked, "And who would examine me?"

Let's face it, especially these days, a college degree increasingly signals its owner to be a mid-wit.

The other development I see is that the economic aspect of a four year degree has come to be emphasized at the expense of academics or learning. Why would anybody study Sanskrit at an elite university? The cost-benefit ratio makes such an endeavor tantamount to financial suicide.

Is the purpose of college to earn a good living or to learn how to lead a good life? If it's the former majoring in business, engineering, etc. on the way to a law degree or MBA is the way to go. If it's the latter time spent in the library reading poetry or listening to jazz might be more productive. Is there any question that in the modern university the balance has been tilted overwhelmingly in favor of career and profession? That's why humanities departments across the country are going bankrupt even as college enrollment has climbed.

And there's one final, even more pernicious effect: college as professional finishing school encourages conformity and acceptance of authority. Keep your head down, your nose clean, study hard for the test, pursue the right extracurriculars: that's the pathway to acceptance at a good school. I recommend _Excellent Sheep_ by William Deresiewicz as an exploration of this topic.