An Assortment of Links, Videos, Comments, Quotes, and Amusements

My thanks to all who subscribed to The Honest Broker in the 10 days since launch. There will be more longform music & culture writing in the next week, but meanwhile here’s an assortment of links, videos, comments, quotes and amusements.

Feel free to share this post with friends.

My favorite performance on International Jazz Day involved two musicians you’ve probably never heard of. Alexey Kruglov played the saxophone from the Ivangorod Fortress, on the Russian-Estonian border, while across the Navra river Estonian guitarist Jaak Sooaar joined in the music-making from another castle.

Even as tensions rise between the two nations—Russia put Estonia on its “unfriendly countries list” at almost the same moment as this performance—these musicians reached for a different kind of dialogue and understanding.

The hottest new music video concept: Igniting your royalty check on the barbecue as protest.

Bad gigs, medieval version: It’s always a bad gig when your instrument starts talking back (from the Howard Psalter and Hours in the British Library, circa 1320).

This reminds me of a quote from Chicago jazz pioneer and raccounteur Eddie Condon, who said of another musician: “He could make the clarinet talk. What it said was ‘Put me back in the case.’”

Speaking of Chicago jazz, here’s a firsthand account from a taxi driver who heard jazz legend King Oliver (1881-1938) perform live—shared by Peter Gerler, who tracked down this source.

“It was dance music, all dancing….And it was before microphones—they didn’t have all this electrified stuff.” And from another source: “Whites on one side of the aisle, blacks on the other, and a rope down the middle.”

Gerler is in the final stages of writing a much-needed biography of King Oliver, who did more than anyone to lay the groundwork for the Jazz Age (not least by hiring Louis Armstrong, and bringing him to Chicago).

People familiar with my writings may know about my (perhaps obsessive) interest in bells and bell towers—and especially with their significance in political debates and even violent conflicts. In many instances, battles were fought specifically to take control of a bell tower, as the ultimate sign of political authority—or, in other cases, revolutionaries sought to destroy the bells because of their alleged tyrannical control over workers and citizens.

Hence I note the new bell tower regulations issued last week in Jefferson, Iowa, a sleepy community of 4,345 residents:

“The Board of Supervisors approved a music policy that outlines requirements that must be followed in order for live and pre-programmed music to be played on the bell tower. Some of the main requirements include not allowing outside requests for music to be made, only certain days and times will be allowed for live performances that are performed by an approved list of 80 maestros, and pre-programmed music will be played after every top of the hour chime from 8am-8pm. . . . Fifty percent of the music that is played must be sacred and patriotic.”

I wonder how one gets added to the “approved list of 80 maestros.”

I predict the next big popular music trend (from a guest Zoom talk I gave to a music history class at a university last week)

Question from Student: In your book you show how innovations in musical styles and trends come from marginalized groups and more oppressed groups in society. I was wondering which way you see this trend going in the future?

TG: I will talk about this, and I will make a prediction—and you can hold me to it. This is one of the most interesting things I discovered in my research. When I started I thought—like everybody—that the key divide in music is between highbrow and lowbrow. Or, put another way, there’s music for the elites and different music of the great masses of people. I thought these were opposed to each other. What I learned is that the high music borrows from the low. I know those are pejorative terms, as they are typically used, so you need to understand I’m talking metaphorically. The key fact is that the music of the masses of people is the engine room of innovation. But here’s the twist: ultimately the people at the highest levels—the elites and authorities—crave the energy of that innovative outsider music.

So here’s my prediction. I just saw an article yesterday about how Sony and other record labels want to expand their positions in Africa. They have ambitious plans to record more African music and, of course, to sell more music in Africa. I listen to a lot of this music, and much of it is very exciting. I believe you will see an extraordinary number of amazing musicians and bands come out of Africa over the next 10 or 20 years.

It makes sense because the music of Africa deserves this attention. It also makes sense because this is the most obvious source of outside innovation in the current-day music world. You’ve heard about K-Pop and J-Pop, but get ready for A-Pop. It will be the next big thing.

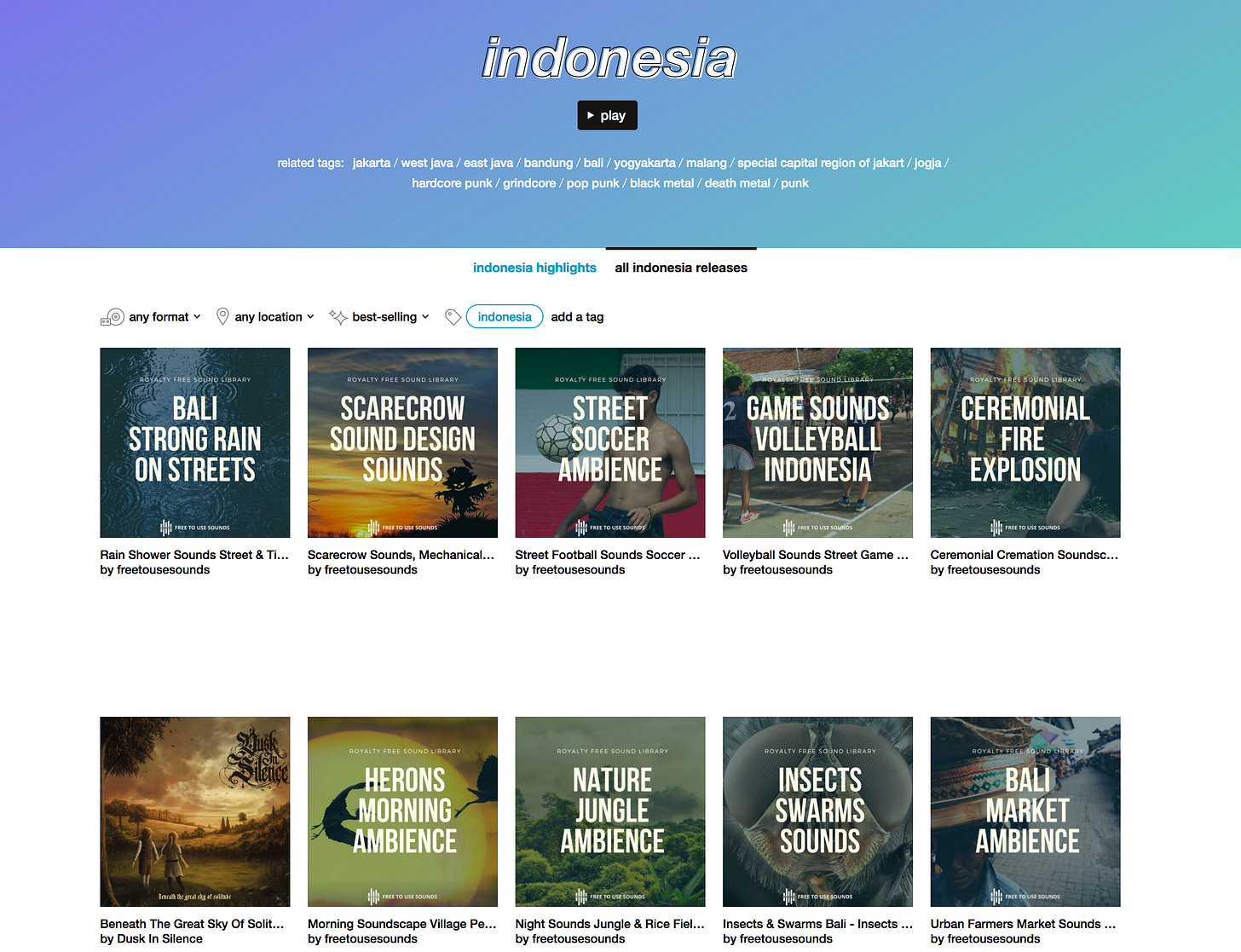

What does musical marginalization look like? Consider a country of almost 300 million people with a rich musical tradition, but when you go to the Bandcamp tag, 9 out of 10 albums shown are collections of sound effects.

Here are 5 recommended recent Indonesian albums (that aren’t sound effects): I hope to do a full article about Indonesian music at some point, but if you’re looking for more interesting albums, consider these.

Meta is an album of jazz duets for prepared piano and guitars from Indonesian musicians Gerald Situmorang & Sri Hanuraga.

Idjah Hadidjah, born in 1956, is one of my favorite singers, and has long resisted Western music industry concepts in favor of a distinctive (and very sensual) regional sound. Check out her work on Jaipongan Music of West Java, recorded at Jugala Studios in Bandung in 2007, but released on Bandcamp last year.

Jono Terbakar X Arc Quartet’s Naturale, released earlier this year, is Indonesian art pop with chamber music ingredients.

Anthology of Contemporary Music From Indonesia is a recent collection of underground and experimental tracks.

Malam Minggu: Saturday Night in Sunda is a recent collection of gently grooving Sundanese dream pop from Indonesia (1978-85).

And, of course, there’s Joey Alexander….

The “blues movement” in Ben Johnston’s Suite for Microtonal Piano grooves along in 13/16. You can follow along with the score here (cued at the 5 minute mark).

The first person officially diagnosed with beat-deafness is Mathieu Dion, a 26-year-old reporter in Montreal. "I just can’t figure out what’s rhythm.”

Here’s a sweet new transcription of Ahmad Jamal playing “Moonlight in Vermont” at the Pershing Lounge in Chicago on January 16, 1958. if you want to learn how to use texture and space in piano trio music, Jamal is your unsurpassed teacher.

You could write a book on boasting, taunting and strutting in the music world—which has a long and venerable tradition from the Hymn of Hammurabi to hip-hop. But a special place in the pantheon belongs to George Bernard Shaw, who wrote this in The Perfect Wagnerite: A Commentary on the Niblung's Ring.

“It is generally understood, however, that there is an inner ring of superior persons to whom the whole work has a most urgent and searching philosophic and social significance. I profess to be such a superior person; and I write this pamphlet for the assistance of those who wish to be introduced to the work on equal terms with that inner circle of adepts.”

From now on, I may start referring to you, dear readers, as “that inner circle of adepts.”

I believe the target of Eddie Condon’s barb was Ted Lewis, whose clarinet prowess was fairly rudimentary.