After 100 Years, Stanisław Lem Is Having His Moment

The melancholy Polish sci-fi sage was obsessed with the dark places where technology veers into incoherence. Have we reached that juncture today?

Have you been following the recent government disclosures on UFOs? If not, you’re missing some truly bizarre news—and it’s straight out of a Stanisław Lem novel.

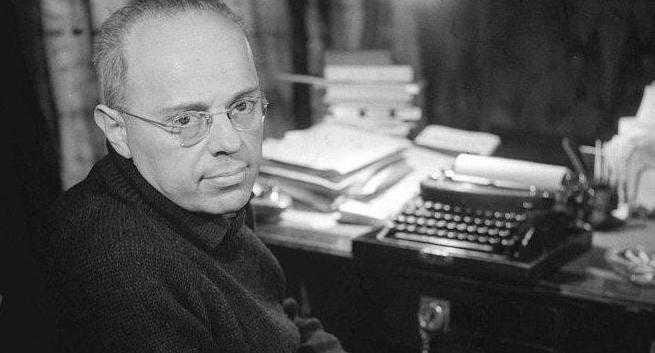

This pessimistic Polish sci-fi writer died 15 years ago, but he is finally having his moment. And it’s not just because we are celebrating his centenary. He’s gotten more relevant because the news is starting to resemble his sci-fi stories.

That’s not a good thing.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Lem was a smart guy, but his stories were all about ignorance. His protagonists never really understand what’s going on—even worse, they don’t have a chance. The situation is beyond human reason. The fact that they are often scientists or intellectuals—the very people we expect to have answers, not just questions—only makes matters worse.

This epistemological fatalism was Lem’s lasting contribution to the subgenre of sci-fi known as “first contact” stories. In these tales, humans encounter extraterrestrials for the first time. Some of the most famous science fiction books are built on this premise—from H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds to Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem. The notion of a meeting of galactic minds never loses its appeal, and some authors devote a whole career to exploring its ramifications. Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhoods End was such a compelling page-turner, he returned to the concept in 2001: A Space Odyssey and Rendezvous with Rama, as well as in other settings. My favorite examples range from the historical zaniness of John Fowles’s A Maggot to the clinical monomania of Philip K. Dick’s VALIS, both mind-expanding in the extreme. Plenty of movies draw on the same theme, and usually in the most dramatic form possible—the extraterrestrials arrive on planet Earth ready for conquest.

Lem took this concept and turned it into something eerie and majestic. The aliens in his stories aren’t trying to conquer anything. We can’t communicate with them or even grasp their motives. In most instances they aren’t remotely like any life form we can understand.

That’s why I thought of Lem when I heard the head of NASA trying to explain the recent rash of UFO sightings, many of them made by experienced military personnel. When asked what these pilots and radar technicians encountered, NASA head Bill Nelson responded:

“They don’t know what it is, and we don’t know what it is. We hope it’s not an adversary here on Earth that has that kind of technology. But it’s something. And so, this is a mission that we’re constantly looking—what, who is out there? Who are we? How did we get here? How did we become as we are? How did we develop? How did we civilize? And are those same conditions out there in a universe that has billions of other suns in billions of other galaxies? It’s so large I can’t conceive it.”

That, my friends, summarizes government wisdom on the phenomenon. In other words, they don’t have a bloody clue. Even worse, what the military pilots saw violates the most basic rules of physics—objects changed positions in inexplicable ways, and moved at incalculable speeds. In fact, there’s as much evidence that these objects came from the ocean as from outer space. The strangest sightings to seem to happen when the UFOs are near the surface of water.

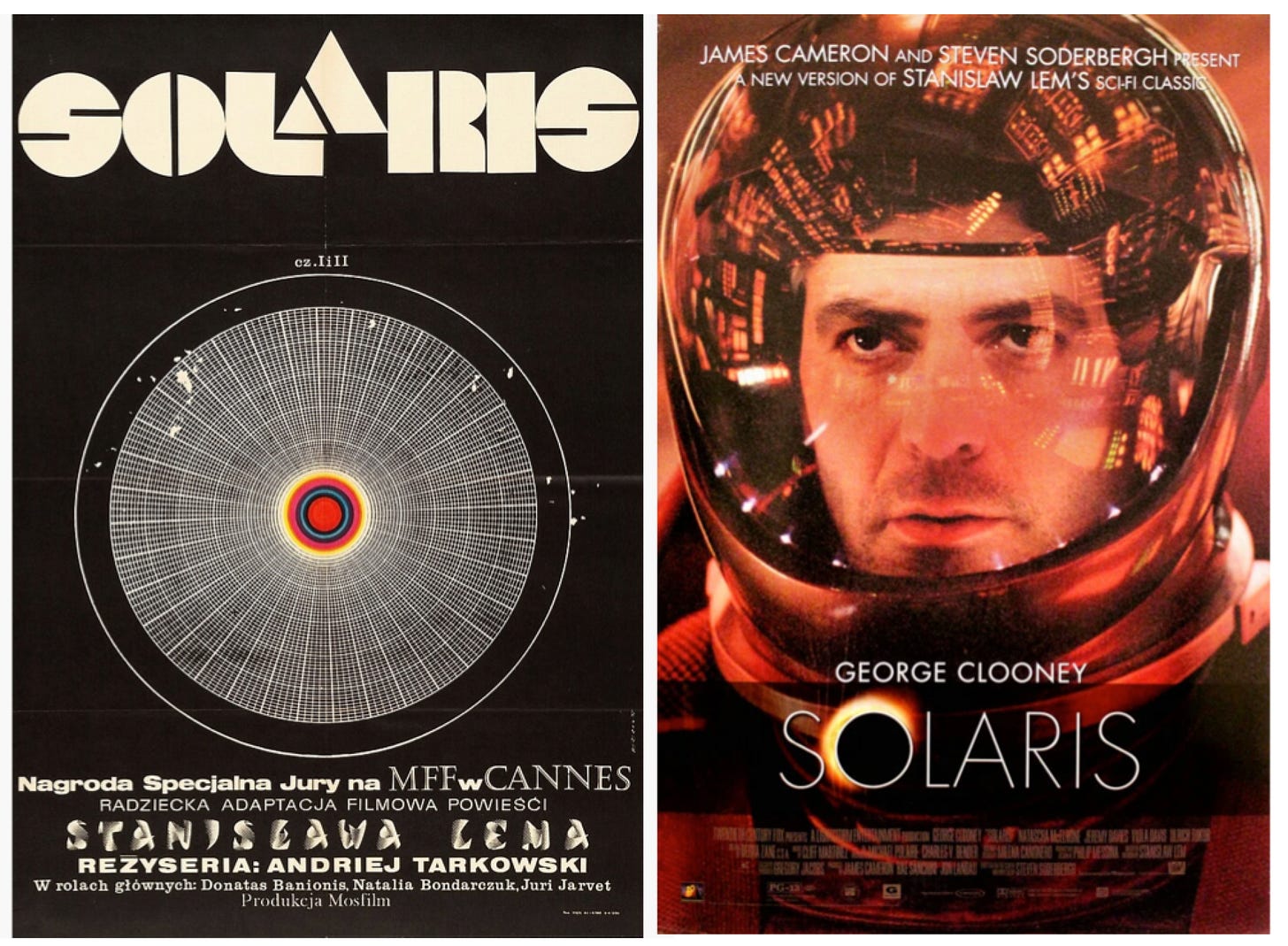

Lem could have predicted this decades ago. His most famous novel, Solaris, describes an attempt to colonize a planet which is simply a large ocean. Yet strange things start happening—inexplicable manifestation that are dismissed as hallucinations. But the more scientists probe, the more inexplicable the results. The ocean of Solaris seems to be causing all this—but what are these strange visible phenomenon and how does a body of water make them happen?

Lem refuses to answer these questions, and it’s not because he’s coy. Or because he couldn’t figure out a better ending for his novel. He wants to tell us that some powerful forces may be impossible for us to grasp. At best, we can learn more about ourselves, and how we handle dark and obscure situations.

With this story in mind, consider the CNN report entitled: “New Leaked Video Shows a UFO Disappear into Water.” I hate to tell you this, folks. But we’re now living on the planet Solaris.

My favorite Lem novel, His Master’s Voice, is one of the most elaborate first contact stories in the annals of science fiction. A team of 2,500 scientists convenes at a secret location in the Nevada desert to analyze mysterious messages from outer space. Lem shows off his smarts and technical knowledge at every turn in this book, and the scientists in his story also have tremendous scope to exercise their ingenuity—and do everything they can to rise to the occasion. But will that be enough to solve the mystery?

No, not in the world of Stanisław Lem. His bleak view of human reason doesn’t allow it. But don’t minimize the achievement here. As hard as it is to write sci-fi that unleashes the imagination, Lem does something far more difficult: he casts light on the limits of imagination. That’s no small matter.

Maybe there’s a lesson here, albeit a painful one to learn. Even after all the warning signs from history, we haven’t advanced much from the blind positivism of the nineteenth century. We live immersed in an technocratic worldview that refuses to grasp any evolutionary path for society that’s not driven primarily by Moore’s law. Even those of us critical of the behemoth digital platforms that define every aspect of our day-to-day life can’t imagine any way of operating outside their scope. We’ve reached a point of incoherence, but only can push more deeply into it. That’s something Lem feared decades ago.

I suspect that the author’s cataclysmic early years contributed to the recurring pessimism of his stories. At the start of his childhood memoir Highcastle, Lem writes:

“I really don’t know when it was that I first experienced the surprise that I existed, surprise accompanied by a touch of fear that I could just as easily have not existed, or been a stick, or a dandelion, or a goat’s leg, or a snail.”

That’s an extraordinary type of childhood anxiety. Do kids really worry about turning into a dandelion? But Lem’s formative experiences were built on a repeated sense that the world genuinely didn’t make sense. In Highcastle he describes his early obsession with inventing things, but these inventions were merely haphazard collections of machine parts and random objects incapable of doing anything—except provide an imaginative outlet for a restless youngster.

Lem reached adulthood at the very moment German tanks were rolling into his native Poland. The liberation of the war led merely to a different tyranny, this time ruled out of Moscow. He cuts off his book-length memoir right before World War II, almost as if the rest of the story is too painful to describe.

We know that his university studies were interrupted by war and annexation. He eventually finished a medical education, but never took his final exams—apparently out of fear that he would be assigned a lifetime job as an army doctor. Instead, he started working as a science research assistant, while writing on the side. His first novel Człowiek z Marsa (“The Man from Mars”) was published in a magazine in 1946, but he also wrote poems and science essays.

Lem’s first major work, Hospital of the Transfiguration, reveals the darkness of his worldview at every turn. This is not a science fiction novel, but a Kafka-esque account of doctors and patients in a mental asylum in the early days of the German occupation, who will soon have the Nazi invaders at their doorstep. The Communist Party censors didn’t like the book, and it was suppressed until Lem could overcome their objections.

His career took off in earnest after the loosening of censorship in the late 1950s. He published an average of one or two books per year, and began gaining a global reputation—extraordinary for any Polish writer during the Soviet Era, but especially for a newcomer to the sci-fi genre, where Anglo-American voices dominated the field.

His works have now been translated into more than 40 languages, but English-language readers are still learning more about this author in his centenary year. MIT Press is releasing new Lem books, including an extraordinary collection The Truth and Other Stories. Many of these tales deal with the same ‘first contact’ themes familiar from his other works, but in surprising new ways.

There are many gems in this new volume, but “The Journal” deserves particular praise—a first-person narrative that might be a manifesto from God, or perhaps the output of a powerful AI system, or maybe the musings of a lunatic, or a voice from an alternative universe. It imparts a sobering lesson: namely that omniscience might simply be a different type of ignorance—a new take on Lem’s favorite subject. In other stories from this collection, protagonists wrestle with inexplicable communications from the most unlikely sources: a computer in a newspaper office, meteors from outer space, perhaps even patterns on the surface of the sun.

Often the inexplicable forces in these stories are a type of artificial intelligence created by humans themselves, but now beyond their ability to control or comprehend. This is another way in which Lem’s fiction from decades ago anticipates the present moment. There are too many news stories to cite in this regard—I even have a hunch that AI is already writing many of the journalistic reports about AI. Just consider the irony and implications of that state of affairs. Suffice it to say that we’ve arrived at a juncture where our own digital creations operate in ways we can barely understand. Even more to the point, that’s the goal of the whole AI project, namely to outstrip human thinking with machine thinking. Here again, we’re living in Stanisław Lem’s troubling universe.

There are now more than forty Lem volumes available in English, but not all of them earn my praise. He often tried to write in a quasi-comical or fabulistic vein. Books of this sort, such as The Cyberiad (1965) or The Futurological Congress (1971), are about as amusing as Robert De Niro’s comedy monologue in The King of Comedy. In other words, the laughs are awkward and unpersuasive. Perhaps the translations don’t capture the zest of the original, or maybe these stories don’t work as well when removed from their original social context in Poland. My hunch is that Lem’s dark humor is 90% dark and only 10% humor—not an appealing mix for the mass market. In any event, I’d suggest you give them a pass.

Even so, the best Lem stories are the most disturbing. In fact, I was struck recently, in returning to this author, how often his tales remind me of H.P. Lovecraft. At first this made no sense to me. I had always considered Lem a densely technical author, a specialist in what they call hard science fiction. This should have nothing in common with Lovecraftian horror. But I’ve come to realize that Lem’s vision of a society in which strange things occur beyond our comprehension is straight out of Arkham. Lem’s science deserves to be taught at Miskatonic University.

The most striking example of this is Lem’s unsettling novel The Investigation. There’s plenty of science here, married to a detective story. But the crime involves dead bodies coming back to life at mortuaries and cemeteries. I never hear Lem’s name mentioned in relation to the horror genre, but he has written some of the scariest tales you will ever read.

That’s one more reason why I’m unhappy when the daily news reminds me of this author. And UFO sightings and AI projects are hardly the only areas in which technology seems to be heading directly into incoherence. Lem gave us a guide to precisely these kinds of experiences. Sad to say, it was a guide that steadfastly refused to provide solutions. That created an uncanny kind of fiction, but one I’d prefer to read rather than inhabit.

In the '70s a friend who owned an SF bookstore had to special order Lem books from the UK and they didn't sell as well as he had hoped.

40 years later I helped another friend sell some of his huge SF collection on Amazon. The same UK Lem editions sold almost as fast as I could list them.

It is telling that many of these sightings take place near water or the ocean. It brings to mind C.G. Jung's essay on UFO's.