A Landlubber’s Guide to Sea Shanties

You don't need to be a sailor to put these songs to work

Few music trends delight me more than the sea shanty revival. In recent months, I’ve encountered them in surprising places, far away from sea and shore. I’m told that shanties even go viral on TikTok—which shivers my timbers big time.

But I’m hardly surprised. There’s something infectious about these songs. You hear them and you immediately want to sing along.

That’s where I can help.

Because if you plan to sing shanties, you need to know the ropes (literally, in this case—see below). You can’t pass as a real salty dog just by shouting out “Ahoy” and “Heave Ho!”

Today I’ll teach you the main types of shanties. Just come on board, and you’ll soon walk the poop deck, or at least cover the waterfront, with confidence.

Don’t worry. I’ll go easy on you.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

If this were an advanced class, I’d make you memorize every part of he Henry B. Hyde. By the time we were done, you’d never confuse a mizzenmast and a spanker boom again, and could distinguish jibs at twenty paces.

But we will skip all that. And head straight to the music.

ROWING SONGS

Rowing songs have flourished separately from the shanty tradition—in fact, these are the original seafaring tunes. A model of an ancient Egyptian boat from 2000 BC, and now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, shows a singer and harpist providing musical accompaniment for the rowers. Even older depictions can be seen in Bronze Age rock carvings found in Sweden.

In ancient Greece, there was a specific job title for the person setting the beat for rowers. This term, keleustes, is often translated as “rowing master.” But beatmaker might be a more accurate rendering.

Long before the rise of sea shanties, almost every society with boats relied on music for exhortation or motivation. Viking ships often employed bards or skalds for this purpose. Christopher Columbus even brought choir boys along on his voyage to the New World. But in other situations, instrumental music was favored—in Venice, for example, regulations specified the number of trumpeters and drummers required, based on the ship’s tonnage.

I suspect that many shanties originated as rowing songs, brought on board by sailors from the Polynesian islands or other places with their own boating traditions. Many of these are upbeat call-and-response songs.

A good example is “John Kanaka,” which probably originated in the Hawaiian Islands before traveling all over the world via sailing ships. As the videos below demonstrate, shanties of this sort can easily turn into drinking songs—but make sure you have a designated helmsman on your crew.

SHORT DRAG SONGS

Have I mentioned ropes yet?

Of course, I did, and for a good reason—there were miles of ropes on some ships. And you were usually pulling them one way or another. The songs varied depending on the demands of the job.

For simple jobs, you sang a short drag shanty. In the words of one sailor, these tunes were used for “only a few pulls, but they had to be good ones.”

So don’t expect a whole oratorio here. A simple song like “Haul Away Joe” will usually do the trick.

LONG DRAG SONGS

Are drag song shows still legal? If you’re a salty sailor, the answer is always yes.

More challenging tasks, such as hoisting the yards, absolutely require an especially spirited drag song—hence these shanties are sometimes call halyards.

These tunes were most often associated with raising or lowering sails. But they were sometimes used in other tasks, such as carrying an anchor or some other heavy object.

PUMPING SONGS

“There is nothing very hard in working the pump-brakes up and down,” explains Frederick Pease Harlow in his memoir The Making of a Sailor (1928), “but to keep them moving, hour after hour, tires the most hardy.”

“Words befitting a pumping shanty were certainly not fit for publication.”

This can be boring work—but also much worse. Harlow complains that there’s often “rain and spray flying in one’s face” in these situations. So pumping shanties were often expressions of utmost irritation. Harlow was unwilling to give many details because “words befitting a pumping shanty” were “certainly not fit for publication.”

Story songs were also popular in these situations. They kept the sailors distracted over a long stretch and made it possible to complete otherwise burdensome tasks.

A good example is “A-Rovin’”—also known as “Amsterdam” or “The Maid of Amsterdam.” This song dates back to Elizabethan days, but the versions preserved in documents have obviously been sanitized, and the more colorful phraseology has probably been lost forever.

According to The Traditional Ballad Index, this song in its original form tells the story of a sailor who “meets an Amsterdam maid, fondles portions of her body progressively, has sex with her, and catches the pox. She leaves him after he has spent all his money.”

Of course, we have apps for that now.

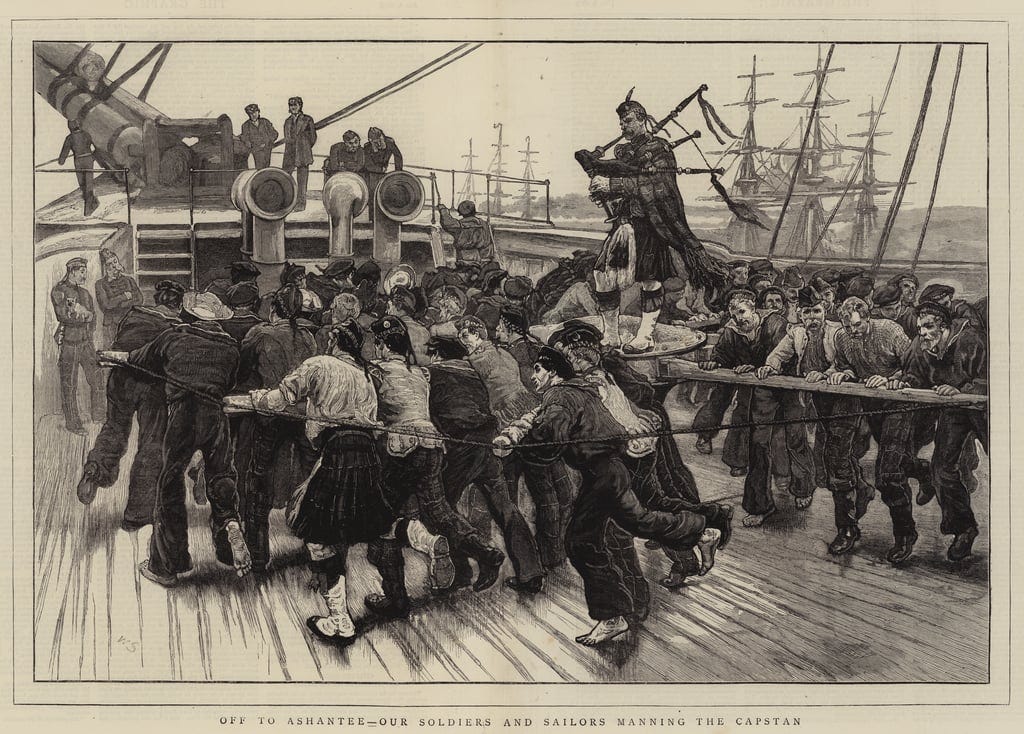

CAPSTAN SONGS

The most physically demanding work on ship often took place at the capstan or windlass, rotating machines that pulled in cables or ropes—some of them huge and supporting heavy anchors. Sailors saved their most inspiring songs for this task, which could require four or more at the handles.

Sailors developed a superstitious faith in their favorite capstan songs. If the work wasn’t going well, they often blamed the tune—and some songs were avoided as cursed due to bad occurrences in the past. But melodies that produced results were viewed as almost magical in their properties. As a result, some of the most popular shanties originated from hard labor at the capstan.

FOREBITTERS

Sailors sang at work, but they also sang at leisure. This shouldn’t surprise you—they didn’t have Netflix or Nintendo back then. So you created your own entertainment, and a sailor who had some skill at it was a valued addition to the crew.

Forebitters were sung for pure enjoyment. A good example is “Spanish Ladies”—which even shows up in the movie Jaws. This song probably dates back to the Napoleonic wars, when the British Royal Navy carried supplies to Spain, and the sailors engaged in a different kind of cross-border commerce.

That wasn’t so hard, was it?

If you’re looking for more information on sea shanties, here’s a visual bibliography drawn from my library. I especially like Stan Hugill’s book on the left, and Richard Henry Dana’s memoir on the right.

I bought Stan Hugill's book a few years back, thinking it would be fun to learn some authentic shanties with my young kids (we are avid sailors). I quickly found that there's not a whole lot of authentic shanties that can be taught to a young kid without quite a bit of "explaining", as in "Let's just not worry too much about the ladies of Timbuktu ok kids?..."

Fascinating stuff, but a pity you didn't mention Stan Rogers, the Canadian songwriter who wrote one of the best shanties ever. If you have a second, I think you'll find this link well worth your time.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B6Nl3PaTimA