A Failed Rock Adaption of Dune Might Have Starred Mick Jagger, Orson Welles & Salvador Dalí (with Music by Pink Floyd)

This gets the top spot on my list of never-made films I'd like to see

I lament many movies that might have been. Here are a few:

Orson Welles wrote the script for his adaption of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and planned out 165 scenes along with special effects—but it proved far too costly to film.

Martin Scorsese once planned a biopic about George Gershwin and had a script by Paul Schrader ready to go, but the project got vetoed by Warner Bros—allegedly because they wanted the director to film a Dean Martin biopic (starring Tom Hanks!) instead.

On the topic of Martin Scorsese, I’ll mention that, many years ago, I sent him a copy of the gritty jazz memoir Straight Life by Art and Laurie Pepper—and suggested that this would be a perfect film project for him. I got a polite letter back from one of his assistants, but the idea went no further. I still think he should do it, but the cast I originally envisioned (a young Ray Liotta as Art Pepper) is no longer feasible.

And I’ll add Spike Lee’s unfulfilled dream of filming Porgy and Bess, Ridley Scott’s never-made version of Blood Meridian, and a nixed sequel to The Sting starring Richard Pryor and Jackie Gleason.

But at the top of my list of dream projects that never happened is a psychedelic adaptation of the sci-fi classic Dune envisioned in the 1970s, with a mind-blowing cast and supporting team.

It was doomed to failure—if only because it aimed so high.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

I’ve written elsewhere of my fascination with this book (here and here), which I tried reading as a young teen and gave up after a few pages, only to return to it thirty years later. On my second attempt, I had low expectations—my standards for literary excellence by this point in my life were based on Proust, Dostoevsky, Woolf, Joyce, Mann, and Faulkner, and even my favorite science fiction books now seemed slipshod by comparison. At an even more basic level, I was a middle-aged man, and thus unlikely to get swept up in some teen cult classic from the past.

Yet Dune the novel genuinely shook me up. Herbert’s planet of Arrakis was just as richly textured as Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County or Joyce’s Dublin, and the multilayered thematic development was ridiculously ambitious. Herbert had written a galactic adventure story, but you could also read it as an ecological parable, or a sociopolitical study or a proto-feminist tract, or a deconstruction of religious systems, or in many other ways.

So I’d have no problem putting Dune on the list of the ten best novels of the 1960s. But for all my admiration, I couldn’t imagine turning this into a movie. And until recently, the history of Dune on the screen seemed to bear out my dark premonitions.

For decades, Dune was a cursed franchise.

Arthur P. Jacobs, who had produced Planet of the Apes and Dr. Dolittle, acquired the film rights from Herbert in 1971, and planned on hiring the best talents in Hollywood for the project. David Lean, famous for Lawrence of Arabia and other screen epics, was slated to direct—who could film desert scenes better than him? Two-time Oscar winner Robert Bolt would write the screenplay. But Jacobs died before filming got underway.

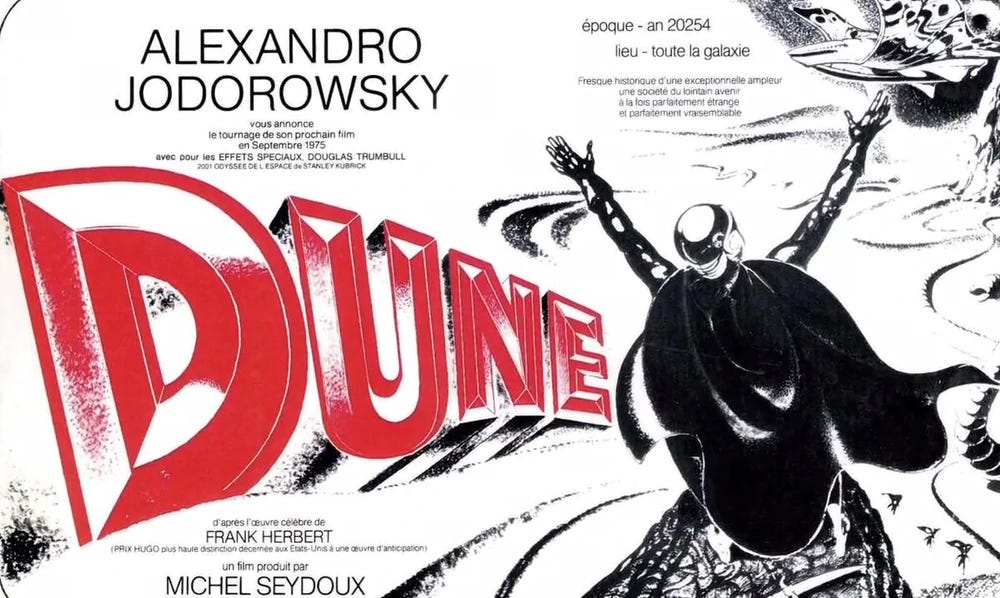

A few months later, Dune film rights were acquired by a French group, and Alejandro Jodorowsky signed on as director. He was an unusual choice, known more for underground cult classics El Topo (1970) and The Holy Mountain (1973)—neither of which made much money.

“Salvador Dalí agreed to play the Emperor at a rate of $100,000 per hour—which would make him the highest-paid actor in the world.”

But Jodorowsky was respected in the counterculture. John Lennon was such an ardent fan that he convinced Beatles’ manager Allen Klein to contribute a million dollars to The Holy Mountain. With these impressive connections, Jodorowsky hatched big plans for a Dune movie that would be even stranger and more ambitious than the book.

He didn’t just want to make a film, but transform society. “I wanted to create a prophet to change the young minds of all the world,” Jodorowsky later explained. “Dune would be the coming of a god— an artistic, cinematic god.”

Maybe the 1960s were over, but Jodorowsky still wanted to change the world. He certainly picked the right book—Dune was a sprawling tale about a charismatic young prophet who remade an entire planet.

And why can’t you make the world a better place with a sci-fi movie?

Jodorowsky raised money to start the project, and spent it wildly. He rented a castle just as a place to write the script—and churned out so many pages that no budget would have been enough to turn them into a film. When novelist Frank Herbert flew overseas in 1976 to check on the status of the project, he discovered a screenplay “the size of a phone book.”

The film would last 14 hours if they had used this script.

Undaunted, Jodorowsky hired comic book artist Jean “Moebius” Giraud to draw storyboards—and soon had 3,000 illustrations to guide his filmmaking. “I used him as a camera,” the director explained. “He drew as fast as a computer.”

Dan O'Bannon was enlisted to do special effects—and was left homeless and destitute after the project collapsed. But George Lucas was sufficiently impressed by his work to hire him for Star Wars a short while later. H.R. Giger was also approached, on the recommendation of Salvador Dalí, and he also went on to a huge success, alongside O’Bannon, on Alien.

But the casting decisions were even more ambitious than the process here. Jodorowsky wanted extraordinary individuals to play the key roles. Mick Jagger was the top candidate to play Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen. Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí would take on the role of the Emperor. Orson Welles was slated to play the Baron. Gloria Swanson would take on the part of the Revered Mother of the Bene Gesserit. David Carradine would be Duke Leto.

And what about the key role of Paul Atreides? Jodorowsky planned to cast his own 12-year-old son Brontis in that part.

And it gets crazier. The director decided that Mick Jagger alone didn’t give him enough rock gravitas. So he decided to hire Pink Floyd to do the soundtrack. The band had just released The Dark Side of the Moon, and was as hot as any rock group in the world.

You might think this was all just a pipe dream. But Jodorowsky started negotiating with these superstars. Orson Welles was perhaps the easiest—he was always chronically in need of cash. He agreed to do the role after the director promised to buy him dinner at his favorite Parisian restaurant after every day of filming.

Salvador Dalí was much tougher in the negotiation. But he agreed to play the Emperor at a rate of $100,000 per hour—which would make him the highest-paid actor in the world.

Most directors would give up at this point. But Jodorowsky agreed, although he slyly planned to get all the footage he needed in just an hour or so, filling in the rest with a robotic mannequin resembling the artist.

Dalí had other conditions. He refused to use a script, because his own lines would be much better. As Emperor of the galaxy, he would sit on a throne that was a toilet seat made from two intersected dolphins— Dalí provided a drawing to ensure that the design was understood. Also, the Emperor’s court would be played by the artist’s real life friends.

Despite these pyrrhic victories, a film of this scope could never be made. Jodorowsky had already spent $2 million on his madcap dream project, and needed to raise another $15 million. But nobody stepped forward to write a check.

Italian producer Dino De Laurentis acquired the film rights to Dune in 1978, and hired David Lynch to direct the project—thus setting the stage for an even bigger financial debacle when the film was released in 1984. That version is now a cult classic, but was considered a failure at the time. Planned sequels were canceled, and most Hollywood experts concluded that Dune could never become a film franchise.

But Jodorowsky’s extravagant concept for Dune continued to have a strange afterlife. A documentary about it was released in 2013, and won several awards. And the director issued a limited edition book with the script and illustrations for his unfilmed movie, which became a collector’s item.

Only twenty copies were made. But one of them led to a bizarre final chapter in this behind-the-scenes saga. A group of blockchain enthusiasts raised $3 million dollars to buy a rare copy of the Dune script and images, via a Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO). They announced their plans to make the material available to the public, while also creating an animated series based on the work.

They also aimed to create Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) of the individual illustrations. Best of all, they would increase the NFT’s value by burning the copy of the book they had acquired.

There was just one teeny-weeny problem. Nobody told the investors that buying a copy of a book doesn’t give you rights to its intellectual property.

I’d like to laugh at these folks, and their foolishness. But Dune is a book about visionaries and dreamers, and seems to bring out those same qualities in people drawn to it. I’d hate to see that disappear. And, after all, in the weird history of this franchise, a few million more sent down the sandworm hole doesn’t really amount to much.

Jodoworsky's such an amazing director. He'd have done something amazing, but it wouldn't have been Dune. The Lynch version isn't Dune either. Nor is this new one. Nor that other mini-series they tried to do. My wife raves all the time about how she'd do Dune like she's been obsessed with it since middle school - she has.

Part of me wishes I hadn't read Dune. Part of me wishes I'd just taken my wife's description of it and written my own version based on the amazing adventure she'd put in my head. I'd write it just for myself. Don't get me wrong - Dune, the book, is amazing - a favorite - but the Dune that preoccupied my imagination based on my wife's passionate rants? To me, that will always be the REAL Dune.

I have to claim a rare disagreement here. As a novel and act of storytelling, Dune is a fundamental failure, one that could never translate successfully to film. Two reasons why:

TL,DR: You can’t empathize with Paul Atreides because the storytelling is broken.

1. From a character standpoint, Dune is structurally incomprehensible. It ignores the lessons of storytelling best explained by Joseph Campbell and indelibly present in every great epic. For a hero’s journey to make a credible emotional impact on the audience, the hero must be a normal person drawn out of his world to struggle and fail repeatedly, before he can conquer the darkness and change the world. Without that development, the audience can’t experience empathy—the sole function and purpose of fiction. In Dune, however, the protagonist starts out as an intergalactic prince with superpowers (not exactly relatable). When he’s drawn out of his world to face his first challenge (stranded in the desert), he inexplicably and immediately acquires even MORE superpowers that make him, instantly, the most powerful being in the universe. He struggles for nothing, except in hand-wavey hindsight exposition. When he has to fight, no big deal—he’s been a magical ninja prince since, literally, the book’s opening scene. Compare this to beloved fantasy characters like Luke Skywalker, Avatar Aang, Frodo Baggins, or Miles Morales from Spider-verse, with all of whom the audience CAN’T HELP but empathize. This is the powerful, instinctual sub-language of storytelling, and why Paul Atreides never feels compelling. Which brings us to…

2. Paul’s only real struggle is to act human—hence why the romance plotline falls flat and exists only as hand-wavey exposition. A good writer can make this work: Homer, for example. Achilles in The Iliad, though a demigod, has to experience the death of Patroclus (his fault, his failure), before he can pass through truly human pain and give the audience a moment of transcendant empathy. Thus, we have history’s first “anti-hero”—a flawed demigod with whom we can still relate because we feel the same pain. Compare to Darth Vader or Prince Zuko in Avatar Airbender: the villain must become a hero himself.

Dune could have done this if the final climactic battle called for Paul to do something very human, to make some personal sacrifice or deny his magical ninja genius powers, allowing us to see our own humanity in him. But in what I believe is among most egregious insults to the audience in 20th century storytelling…Herbert doesn’t even write that scene! He skips over the climax battle entirely! It doesn’t exist! It’s just infuriating hand-wavey aftermath exposition!

Thus, despite the magnificence, beauty, and even genius of Herbert’s world-building, the story is a failure because it contains no humanity. Paul Atreides isn’t a hero, nor an anti-hero, but the villain. And nobody wants to see the villain win.

(I’m still a fan though.)