A 2000-Year-Old Argument Over the Flute Is the Most Important Thing in Our Culture Right Now

This bitter debate from ancient times helps us understand today's crisis in music and other creative fields

Economists have strange opinions about musicians. For example, Adam Smith claims in The Wealth of Nations (1776) that music ranks among the “most frivolous professions.”

At different points in his book, he compares musicians to buffoons and prostitutes. Even slackers who can only make the head of a pin get more respect from him.

Mr. Smith especially hates opera singers—which is interesting, because they were the most highly paid performers in those days. During the 18th century, opera singers earned more than the most successful composers.

So Smith pursues a strange view of economics. He loves the marketplace—except when it rewards musicians.

He insists, contrary to all evidence, that a song must be worthless because it “perishes in the very instant of its production.” In other words, a transformative musical experience possesses no value, no matter how powerful.

And it’s not just Adam Smith who thinks so. Even today, some economists will tell you that music has no economic value.

If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (for just $6 per month).

It’s even scarier when people who control our music culture make the same claim.

Whenever I hear a tech CEO refer to music as “content,” I can’t help but get reminded of Adam Smith’s condescending view. Judging by what these CEOs pay for songs—only a fraction of a penny per performance—they clearly agree that music is ephemeral and worthless.

So we shouldn’t be surprised that the CEO of Spotify recently made a claim very similar to Adam Smith’s. He insisted that the cost of making music is “close to zero.”

But here we encounter the same contradiction that undermines Smith’s view. Many musicians tell me that they need to spend ten thousand dollars or more to release a professional recording.

So how can music cost nothing if it requires so much investment (and I’m not even counting the time involved in practice and developing mastery of a musician’s craft)?

I have a different view of the value of music. I believe music is a source of enchantment and a change agent in human life. So in my economics, a song can possess great value.

I suspect that many of you feel the same.

We have lots of evidence to support this. Many fans are currently paying more than a thousand dollars to attend a Taylor Swift concert. That’s actually the biggest trend in our culture right now—people want to tap into the transformative power of song in live performance (not streaming, thank you very much Mr. Spotify CEO).

So what is going on here? Is music worth a lot. Or is it worth almost nothing.

Now here’s a curious fact. This same confusion about the value of music existed more than 2,000 years ago in ancient Greece.

We can learn a lot by seeing how they resolved it.

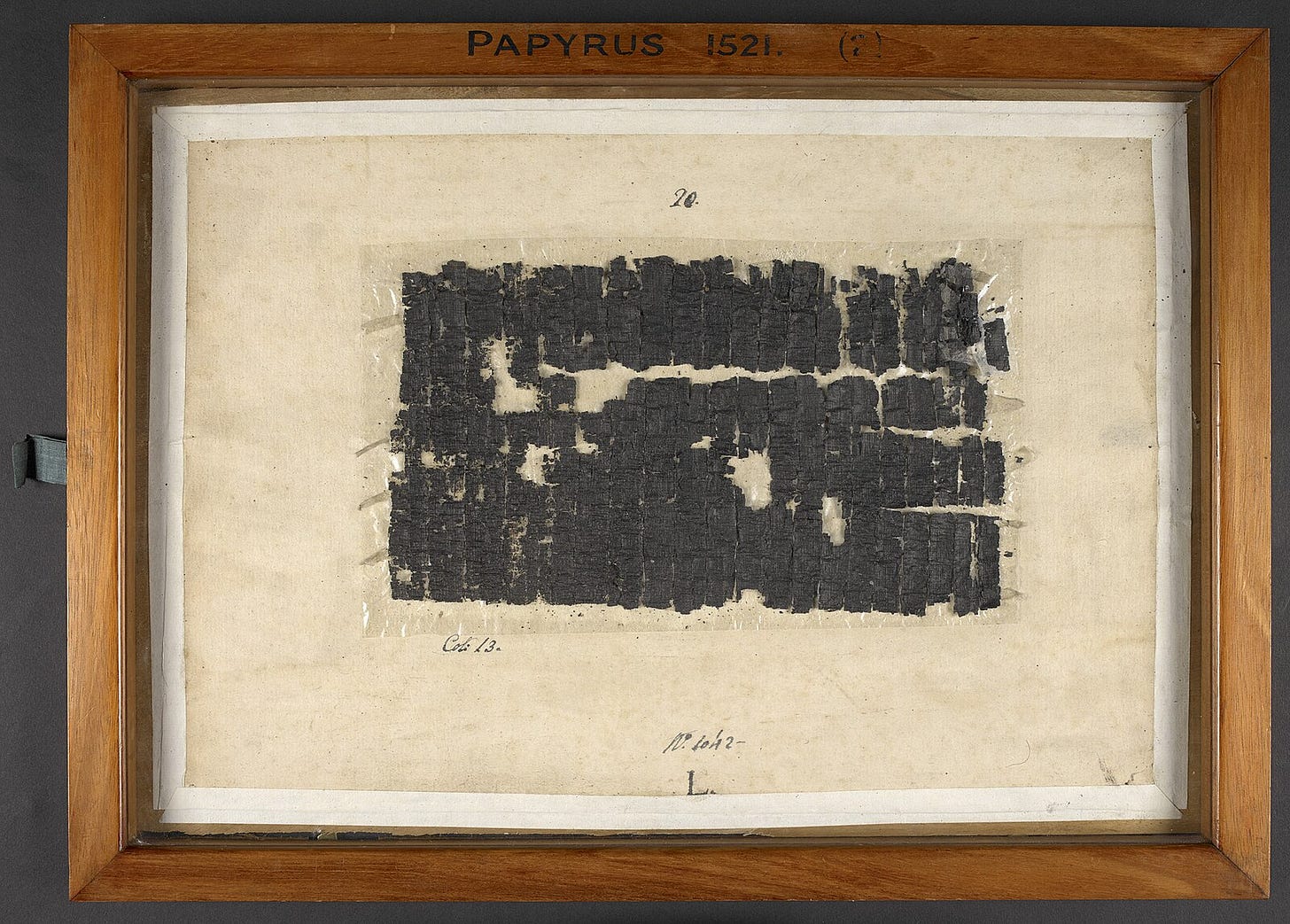

Just a few months ago, we learned new details about the last days of Plato. They came from a charred papyrus that survived the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

Until now the scroll was indecipherable, but finally—with the help of advanced imaging equipment and other cutting-edge technologies—the words could be read.

And they tell us about music.

Plato spent his last hours listening to a female Thracian slave play the flute. And he complained that she wasn’t playing well. He was especially displeased by her poor sense of rhythm.

This is shocking to anyone who has read Plato’s Republic, where he criticizes the irresponsible person who “drinks heavily while listening to the flute.” He attacks fans of flute music even more savagely in his dialogue Protagoras:

Such is their lack of education [they] put a premium on flute-girls by hiring the extraneous voice of the flute at a high price [Ted’s addition: Take that, Adam Smith]….But where the party consists of thorough gentlemen who have had a proper education, you will see neither flute-girls nor dancing-girls nor harp-girls, but only the company contenting themselves with their own conversation, and none of these fooleries and frolics

But who does Plato want at his side when he is dying? His attention is focused on—not family or friends!—but…

a slave, who is

a woman, who is

a foreigner, who

plays the flute.

That’s a quadruple whammy—and totally out of character for Mr. P.

[Let me note in passing, that I translate the Greek aulos as ‘flute.’ This is not a perfect rendering—the aulos was a double reed instrument, perhaps more like an oboe. But it’s almost always translated as flute by scholars, so I stick here with the convention.]

The deciphered text from the charred scroll also provides details about where Plato was buried. We now know that he was laid to rest in a garden next to the Mouseion, a shrine to the Muses—the etymology of the word links it to music. The Muses were goddess patrons of music, dance, poetry and other arts.

All this is quite extraordinary.

That’s because Plato’s philosophy is so hostile to musicians and poets. He even banishes them from his ideal Republic. But he must have had a kind of conversion moment in his final days, and thus aligns himself with music and the arts.

And the story gets even stranger. That’s because Plato’s mentor and hero Socrates also had a conversion experience at the end of his life—anticipating Plato’s later turnabout. Socrates even claimed in those final moments that he should have been a musician himself.

“In the course of my life,” he explained, “I have often had intimations in dreams ‘that I should make music.’”

I’ve written a lot about music coming from dreams—there’s probably no music critic on the planet who writes more about sleeping than me. So this admission by Socrates is significant.

But what he says next is even more fascinating:

“The same dream came to me sometimes in one form, and sometimes in another, but always saying the same or nearly the same words: Make and cultivate music, said the dream. And hitherto I had imagined that this was only intended to exhort and encourage me in the study of philosophy, which has always been the pursuit of my life, and is the noblest and best of music.”

In other words, the wisdom of philosophy transforms it into a kind of music. From that perspective, musicians pursue the most blessed vocation possible.

As you can see, the ancient Greeks (like Adam Smith) were hopelessly confused about the flute. Even the experts couldn’t make up their minds.

Sometimes they think music is worth nothing. Sometimes they think it’s worth a lot.

For example, Aristotle intensely dislikes the flute:

The flute is not an instrument which is expressive of moral character; it is too exciting….The ancients therefore were right in forbidding the flute to youths and freemen, although they had once allowed it….There is a meaning also in the myth of the ancients, which tells how Athene invented the flute and then threw it away.

But political philosopher Hannah Arendt—who had deep knowledge of Aristotle and Plato—tells us that flute-playing was admired as one of the three great vocations among the ancient Greeks.

“It was precisely these occupations—healing, flute-playing, play-acting—which furnished ancient thinking with examples for the highest and greatest activities of man.”

Why are these three professions so glorious?

According to Arendt, they are superior to other forms of work and labor, which only have meaning when they create products for use and consumption. But music, like healing, is good in itself—it doesn’t need further justification.

This is the exact same reason why Adam Smith hates music—it serves as an end in itself, and not a product for exchange. But for Arendt this is music’s greatest glory.

She explains that the ancient Greeks especially admired actions that “create their own remembrance.” It’s almost as if she had read this news story from earlier this week.

In other words, songs aren’t just means to an end—like a manufacturing process—but are complete in themselves. Just by existing, they do something magical, even without proving their exchange value in a marketplace.

As such, they rank higher than any mere consumer product, destined to be used up (and hence not achieving remembrance).

This is how I perceive music. This is probably how many of you cherish music, too.

Anybody who loves music, knows how powerful these songs are. They really are like drugs—Plato wasn’t wrong in comparing them to intoxication. Aristotle wasn’t wrong in claiming that they are dangerously exciting.

I raise all this because these Greek arguments about flute players are almost identical to disputes over music in today’s culture.

We have two camps, and you really need to pick a side:

(1) The dominant view in the economy treats music as something of little consequence or value. You shouldn’t even have to pay a penny to hear it. And if it can be replaced by an AI track—or even a podcast or twerking video or some other form of ‘content’—that’s perfectly fine. That’s because musicians don’t create sufficient value to deserve better treatment.

Or you can align yourself with the other view:

(2) Music is our most trusted pathway into a world of beauty and enchantment. It transforms our lives in a way that everyday products of consumption can’t replicate. And even though it is intangible, it endures longer than these consumer goods. At the end of your life, you will still turn to your beloved songs for comforts, long after other products have worn out and lost their value.

Make no mistake, this is a huge issue. The wealthiest people in the world—namely, the owners of the dominant web platforms—are trying to subjugate all cultural endeavors (or as they call it, content) in their digital domains. But this can only happen if they are allowed to manipulate the economy value of creativity, and force it into subservience to their centralized technologies.

We can’t afford to let that happen. So, as you might guess, I have an easy time picking (2) above as my chosen pathway.

And it’s not just my opinion. Plato and Socrates finally came to the same conclusion at the end of their lives. Is it too much to hope that the people who control our music economy will eventually make that same discovery?

The Memory for Music section makes me think of the Jean Michel Basquiat lines

“Art is how we decorate space;

Music is how we decorate time.”

Our memories are of moments in time.

A passage from Plato’s Laws is quite informative here (Book III, I believe). He makes a distinction between playing or dancing well, and the nature of the content actually being performed ie that not only the performance is “good,” but that what’s being performed is itself actually good. Two very different, yet intimately connected questions.

One can perform a Taylor Swift song very well, but is that the same as performing a Mozart violin concerto very well? Wherein lies the difference and is it just a matter of taste? What happens to a society that sees no difference?

I think that’s the central paradox being posed by Plato.

Plato also called songs “charms.” But here again, there are different kinds of charms… What exactly is society allowing itself to be charmed by? Are we allowed to ask that question, and what happens when we do? Are there both good and bad charms?

I think Plato, along with many others, were arguing that all is not just a matter of taste. In fact, the question of taste is of the highest civilizational, cultural and metaphysical significance.

A mature society cannot avoid these questions. And Plato, I reckon, would say that we ignore these questions at our own peril.