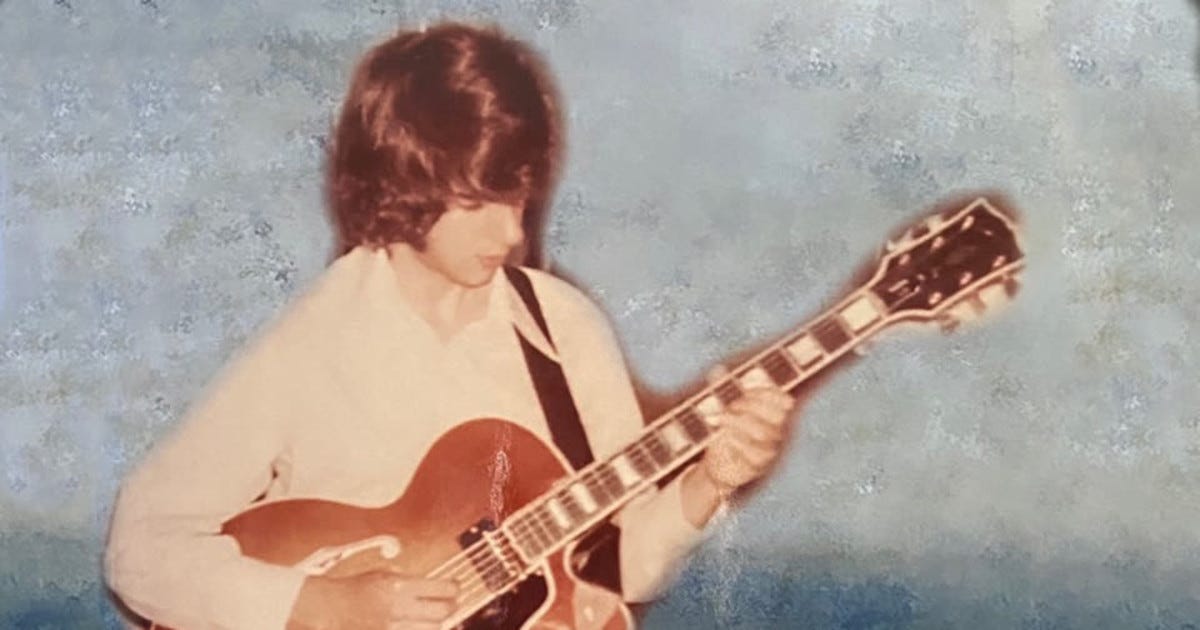

9 Facts About Guitarist Pat Metheny as a Youngster

You don't need to be a future guitar hero to learn from his example

We need more books about the childhood and early development of jazz musicians. There are almost none—a peculiar fact, given the public’s fascination with musical prodigies. Our interest in these precocious youngsters is more than just idle curiosity, but broadens our grasp on the rare ingredients needed for greatness.

Is it nature or nurture—or pure chance, or some combination of these qualities? Is a music career available only to the gifted few, or can discipline and practice provide a pathway for the many? These are deep issues with wide-ranging implications for parents, teachers, schools, and communities—and, of course, musicians themselves.

That’s why I looked forward to reading Carolyn Glenn Brewer’s Beneath Missouri Skies: Pat Metheny in Kansas City 1964-1972—which focuses entirely on the famous guitarist between the ages of 10 and 18.

Below are 9 things I learned:

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

9 Facts About Guitarist Pat Metheny as a Youngster

(1) As a baby, Metheny made up his own lullabies, and sang himself to sleep. I haven’t heard of this happening before. I’m not sure whether this indicates musical talent, but it certainly demonstrates a commitment to improvisation.

(2) Metheny’s family was suspicious of the guitar, and tried to discourage Pat from learning the instrument. They eventually relented, but he needed to agree to play French horn in the school band in exchange.

(3) As a youngster, Pat practiced intense listening. He later explained that it’s more important to listen to a few good albums very closely than to skim superficially over lots of music. He identified the following albums as especially important in his development.

Miles Davis: Four and More

Ornette Coleman: New York is Now

Gary Burton: Gary Burton in Concert

Wes Montgomery: Smokin’ at the Half Note

(4) Metheny’s interest in the guitar was furthered by hearing the Beatles in their historic appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. The same week that Pat celebrated his 10th birthday, the Beatles movie A Hard Day’s Night was released. Metheny saw it five or six times before its run ended at the local movie theater.

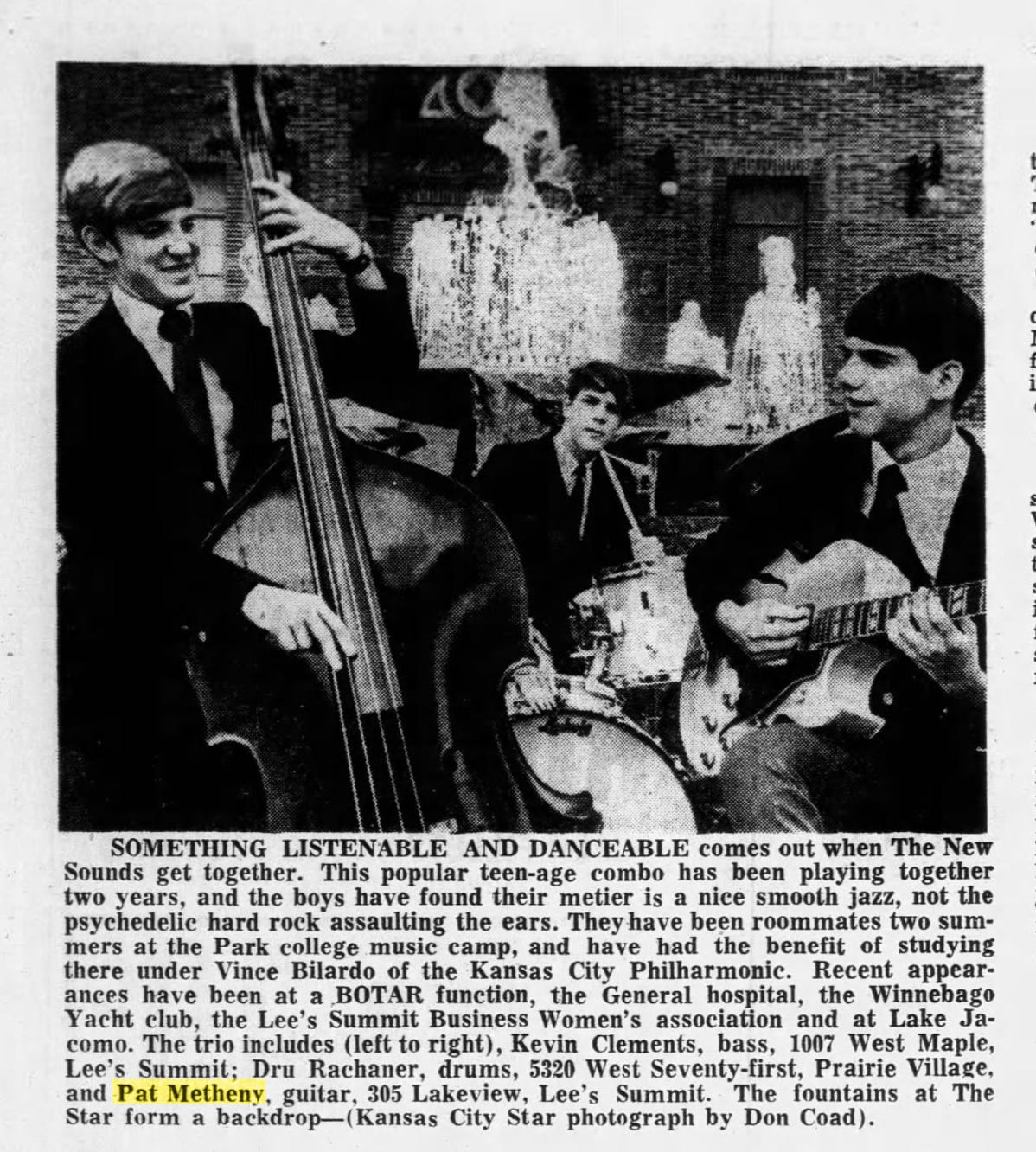

(5) Pat picked a good role model. At age 13, Metheny got a chance to see his hero Wes Montgomery perform live—just 7 weeks before the guitarist’s death. He and his brother returned from the concert dazzled by the music, and with an autograph from Montgomery himself. Pat’s mother had it varnished and hung on the wall. Even today, so many decades later, you can hear how deeply Metheny internalized Wes’s holistic approach to phrasing, and like his role model avoids empty histrionics and showboating (rare austerity for any instrumentalist but perhaps especially guitarists). Metheny, for his part, still cites Montgomery’s Smokin' at the Half Note as “the gold standard of what is possible to achieve in music.”

(6) He put his music out there with confidence, even at a very young age. When Pat was just 15, he read about a jazz competition sponsored by Downbeat—winners would get a scholarship to the National Stage Band Camp. Pat put together a tape showcasing his performance of a Wes Montgomery tune “The Big Hurt.” He sent it to the magazine, but never got a response. Pat actually won the scholarship, but the magazine had forgotten to notify him. He only learned about it when he saw his name in a follow-up issue. His mother phoned the Downbeat office, and they confirmed that her son had been awarded a full scholarship.

(7) He bounced back from rejection, sometimes unfair rejection. Another miscommunication prevented Metheny from playing with his quintet at the 1971 Kansas City Jazz Festival. The band took special care in recording a high quality audition tape in the choir room of the local junior high school—which had an Ampex tape deck. Metheny sent it to the festival organization with high hopes, but never heard back from them. He phoned the concert promoters for feedback and was told they had no recollection of ever receiving the tape. The band had sent the only copy, so they had no backup to provide. Metheny wasn’t discouraged, and his relentless efforts paid off with a spot on the festival line-up the following year.

(8) Metheny learned from every gig. His big music job in 1971 was in the lounge of a Ramada Inn, a chain motel located at Interstate 70 and Noland Road in Independence, Missouri. (There are still three cheap motels there, where you can stay for as little as $58 per night.) “It was actually quite illegal,” Metheny later commented—probably because he was too young to perform in a place that sold alcohol. Pat was required to get a permit from the Kansas City mayor’s office, and also needed the support of the Kansas City Musicians’ Union. His mother had to drive him to City Hall, where he was interrogated, but eventually given a permit—with the stipulation that he leave the premises between sets.

(9) Metheny built his skills rapidly during these formative years, but it took total commitment. What was his secret? Here’s his explanation: “I would literally practice and listen to records probably twelve hours out of a day. I would play every second I could, and if I wasn’t playing, I was listening to a record. I think if you’re going to deal with this general area of musical language, you have to do that….I would say there’s no way around it. The music is too hard.”

Why do I share these facts? They are entertaining enough as anecdotes, but there are deeper lessons here.

First of all, we can learn from these stories even if we aren’t destined for superstar music careers. But we also see how much even the greatest talents require support and nurturing, as well as personal habits of discipline and hard work. We discover, too, how many obstacles even artists of exceptional potential face—and must overcome—during their formative years.

It’s good to keep all this in mind in our dealings with young people who are in the early stages of their own personal and vocational development—musical or otherwise. Maybe we can be one of the helping hands, and not just another bottleneck.

And finally, these stories serve as a reminder of our own struggles during our childhood and teenage years—when, perhaps, a few caring people tried to help us along the way. In some instances we can still reach out to them with thanks, which is always a good thing to do. And even when that opportunity is no longer available, we can at least pay them private homage in our thoughts. You certainly don't need to be Pat Metheny to take that small step.

Good story. I feel (for me) # 3/4/5 were most important.

I even got to meet one of my Role Models when young - George Benson - who was already following in the mold of one of my other Heroes - Wes Montgomery. I was at that George Benson gig the 1st 3 nights he was in that club. This was not long before he had his 1st huge pop hit -This Masquerade. It was early in the week & quiet in that club, which was how I liked it. Was able to sit directly in front of him every night. I got to meet him, & on breaks he sat with me several times & really responded to my Wes questions. He demonstrated several techniques & tips. What a super Gracious fellow he was to me, a young worshiping neophyte.

I knew he sang, because I had heard his Big Boss album (my Guitar teacher), but had no idea he was so phenomenal as a singer. He said (right before his huge hit ,"ya ,my manger has been after me to do more singing". Funny - he influenced me to start singing as well, which led to many things for me beyond just being a Guitarist only.

“I would literally practice and listen to records probably twelve hours out of a day. " The difference is he innately knew what to practice and what to listen to. I think that is a huge part of the talent that is greatly overlooked. I am also sure he hear's it differently than I hear it...I would imagine he hears it with incredible depth and attention to nuance I cant even recognize.