8 Ways of Connecting a Smartphone Can't Deliver

They are the pillars of a happy life. So why are they under such fierce attack?

We live in a materialistic society, but all the evidence tells us that happiness doesn’t come from what we own.

When you look back at all the missed chances in your life, none of them will involve Amazon Prime Day or Black Friday at Walmart.

Instead, the single best predictor of people’s happiness is the depth and breadth of their social connections.

If you want to support my work, consider taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

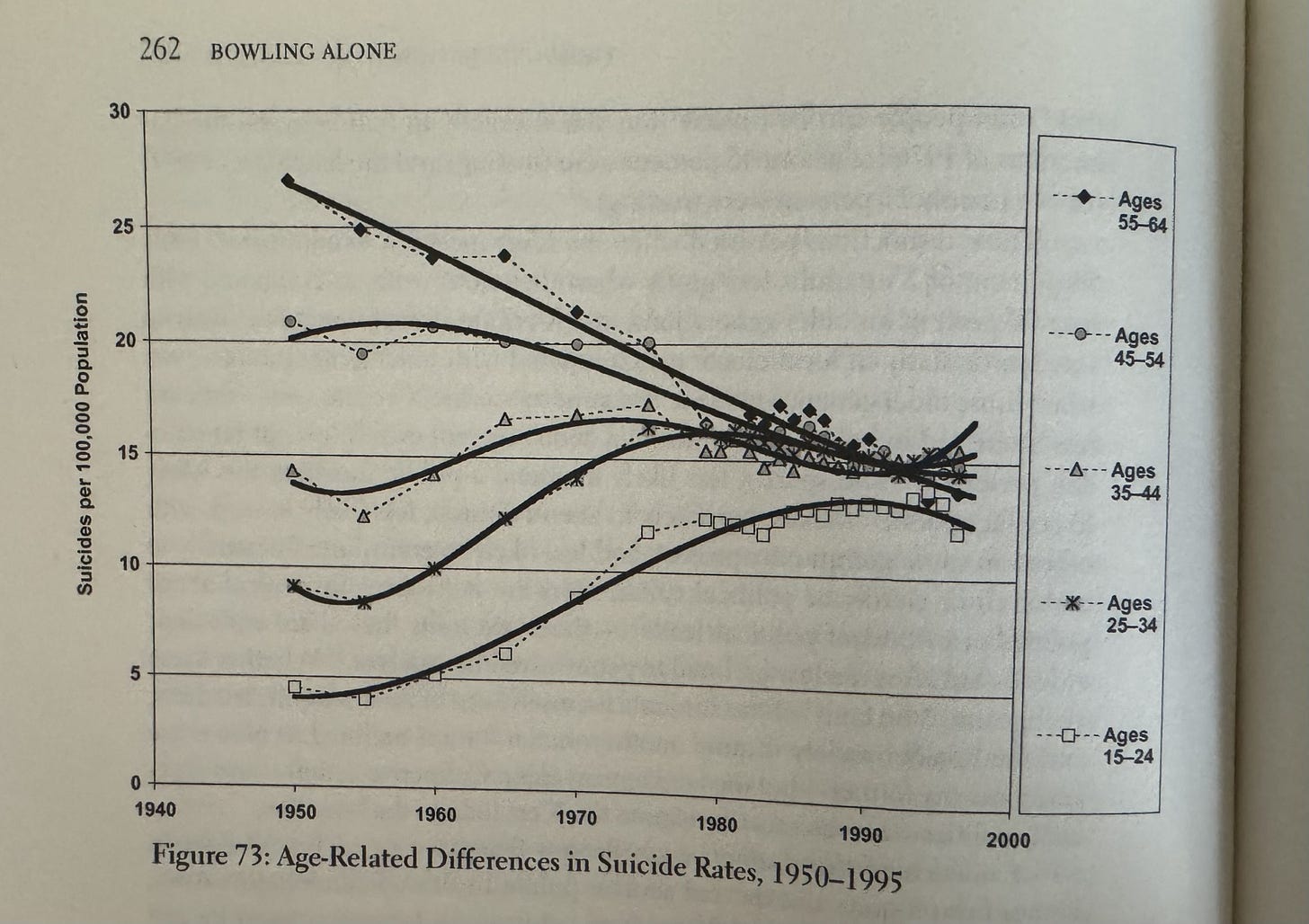

Robert D. Putnam made this point powerfully in his 1995 book Bowling Alone. Here’s one chart from his book that I found especially alarming—it looks at suicide rates of different age groups.

In an earlier day, old people committed suicide more than any other group.

Perhaps they had a fatal illness. Or maybe life had knocked them around so much they just gave up. They couldn’t cope anymore.

But then it all changed. Older people got happier—current research indicates that life satisfaction peaks after age 60 (by the way, that matches my personal experience). But young people started losing hope.

That’s our new normal.

Here’s Putnam’s commentary on this.

As the twentieth century ended, Americans born and raised in the 1920s and 1930s were about half as likely to commit suicide as people that age had been at midcentury, whereas Americans born and raised in the 1970s and 1980s were three or four times more likely to commit suicide….

Some new malaise had entered the world, it seemed. And it struck at younger people—somehow bypassing older generations.

“Clinical depression is a prime risk factor for suicide,” Putnam noted—so he wasn’t surprised to see it rising in these same younger groups. Other symptoms of “malaise,” as he calls it, follow the same pattern.

What was the cause? Why were older people coping, but their children and grandchildren suffering?

Putnam believed that the single biggest risk factor was the growing amount of time people spent alone.

Even back when he wrote Bowling Alone—before smartphones and apps—teens were solitary for three-and-a-half hours per day. Adolescents spent more time alone than with their family.

For the first time in history, people were growing up disconnected—and were suffering psychically from their isolation.

There’s heavy irony in the fact that Putnam was writing at the dawn of the age of connectivity. But that’s exactly what youngsters were not getting—connected—and it was about to get a whole lot worse.

In the years following the introduction if the iPhone in 2007, suicide among ages 10 to 24 skyrocketed 62% in the US. By 2021, almost one-third of teenage girls admitted that they had considered taking their own life.

In a more recent survey, more than one-fifth of high school females admitted to making a suicide plan during the previous year.

Experts continue to debate the causes, but most Americans have already identified the main culprit. Some 53% of Americans now believe that social media is fully or predominantly the cause of teen depression.

Connectivity via the phones is causing disconnection with actual life—disrupting mental health in a way no previous technological shift could come close to matching.

That’s what parents think. That’s what teachers thinks. That’s even what teens themselves think.

There are some dissenting voices—tech accelerationists blithely optimistic about the digital-driven life. But even Silicon Valley elites are now restricting smartphone use among their children.

So look at what they do—not what they say publicly.

“No other addictive device has ever been so pervasive,” now warns Harvard professor of psychiatry Judith G. Edersheim—who says the effect is akin to putting youngsters into a 24/7 casino, and serving them chocolate-flavored booze.

Web platforms want to get children addicted as young as possible—because that increases the lifetime cash flow they generate for the corporation.

“The lifetime value of a 13 y/o teen is roughly $270 per teen,” coldly assesses an internal Meta memo. That’s how they view youngsters from inside the technocracy.

TikTok has done a similar analysis. They know the risks—but just don’t care.

Internal documents from TikTok reveal how carefully they have studied the addictive properties of their app. They actually calculated how many videos you need to watch in order to get hooked—260 videos, or around 35 minutes of scrolling.

I’m reminded of the scandal at Ford Motor—when they knew that the fuel tank in the Pinto could erupt into flames after a collision. They could fix it at a cost of ten dollars per car.

But they did nothing.

Ford calculated that 180 drivers would burn to death, and each would result in a $200,000 payout. It was cheaper just paying that money to victims’ families than recalling all eleven million Pintos and installing a safer fuel tank.

This is the same kind of math they’re doing at the big web platforms right now. The money they make from addiction more than offsets their cost from dead teens and ruined lives.

In 1995, Putnam was concerned about teens who were alone 3.5 hours per day. But nowadays teens spend up to nine hours daily staring into screens, according to the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychology.

Meanwhile, the amount of time spent with friends has dropped markedly The number of social outings has declined too. Almost every metric of connectedness in the real world (as compared with online ‘friends’) has plummeted.

These are alarming statistics but the don’t even begin to capture the total assault on connectedness that’s currently underway.

Here are my eight pillars of connection—and none of them require Wi-Fi access.

If you want a happy life, you nurture them. If you let them all topple, you’re at grave risk.

Connection with the natural world;

Connection with family, friends, neighbors, colleagues;

Connection with history and tradition;

Connection with the community via institutions and organizations (e.g., civic engagement);

Connection via charitable acts, and giving (material and emotional) support;

Connection with spiritual and other metaphysical or higher values—sources of meaning outside the materialist realm;

Connection with creative human expression in art;

Connection via all those other things a computer can't provide (love, forgiveness, fidelity, trust, empathy, kindness, etc.).

Here’s the saddest part of the story. We all recognize the importance of these things—yet each one of these connections is currently eroding in society.

It’s even worse—they are all under attack simultaneously. That’s true whether we’re talking about the natural world, or friendships, or civic engagement, or whatever.

That’s a stunning thing to consider.

“Your smartphone can order an Uber driver or delivery pizza, but it can’t give you a glorious sunset or gratitude or a trusted friend—or any other form of genuine connectedness.”

Why do we let this happen?

Sure, we all love our tech devices—but are they more important than love, family, friends, the environment, forgiveness, and all our other deepest values?

I’m often a harsh critic of dysfunctional tech—and it certainly has its share of blame here. But nobody is forcing us to abandon these vital connections.

Every type of connectedness listed above is within our grasp—we don’t need anybody’s permission.

Nobody can stop us from loving, art-making, civic engagement, connecting with nature, or pursuing other pathways to connectedness. But don’t expect to find an app for any of these things.

Your smartphone can order an Uber driver or delivery pizza, but it can’t give you a glorious sunset or gratitude or a trusted friend—or any other form of genuine connectedness.

“Loneliness was never easier to find than right now in our digitally connected world. It’s literally sitting in the palm of our hand.”

At best, the phone can serve as a tool. But, too often, it’s a distraction instead. Or—increasingly in the Age of AI—a deception, offering fake constructs that imitate real human connection.

That’s the updated story of Bowling Alone—namely that you don’t even need to go to the bowling alley to do it anymore. There are plenty of virtual bowling apps for solitary use.

Loneliness was never easier to find than right now in our digitally connected world. It’s literally sitting in the palm of our hand.

If you’re raising children, you should nurture these connections as a way of modeling healthy behavior to them. This is also true if you’re a teacher or boss or minister or doctor or counselor—or anyone else who has some responsibility for others.

That’s a wide net. In some ways, we are all responsible for others.

But just do these things for yourself, too. And start right away—because if you wait for your phone to remind you, it will never happen.

Because none of the 8 can be monetized in an attention economy

With due respect, I would like to suggest that injunctions to "get off your phone" and "find meaningful connection" are somewhat ineffectual.

That it is up to the individual to prevent her domination by devices distributed and marketed by gigantic, rapacious, autocratic, concentrated centers of undue economic power, or that it is up to the individual to deal with the consequences of such domination — such a notion is precisely the myth tech companies would prefer circulating around the culture. For it is a de-politicizing myth shifting the balance of blame and responsibility from them, and from the neoliberal policy-makers and financiers whose decisions in part established the very political-economic conditions that have made it profitable for tech companies to deliberately addict us.

Getting off your phone is a worthwhile goal, and offline connection is indeed a true good. But it is only under certain conditions that it becomes really possible to exercise personal agency, while under others, it becomes practically impossible. Don't just aim for finding connections; aim for the collective determination of political-economic arrangements that conduce one toward establishing local, community connections.